In June, I went to the Digital Humanities Summer Institute (DHSI) in Victoria, BC. I have a whole other post in my head about the ferry journey from Seattle to Victoria (beautiful!), the fish tacones at Red Fish Blue Fish (delicious!) and the nineteenth-century architecture of the city (magnificent!), but for now I’ll stick to the subject at hand: encoding the Four Zoas.

We’ve written a few posts already about our experiments with the Four Zoas, so if you need a recap go here or here.

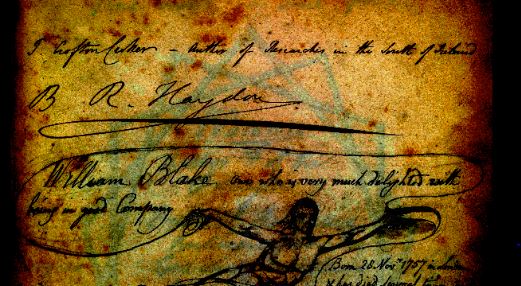

DHSI is an annual convention that combines a week-long seminar with a series of workshops, lectures, and other events. I took a course called ‘Text Encoding Fundamentals and their Application’ led by Constance Crompton, Emily Murphy and Lee Zickel. The class covered the theory and practice of encoding electronic texts for the humanities. We were all asked to bring a project that we could practise our newly-developing skills on and so I took one of our high-resolution images of a page from the Four Zoas.

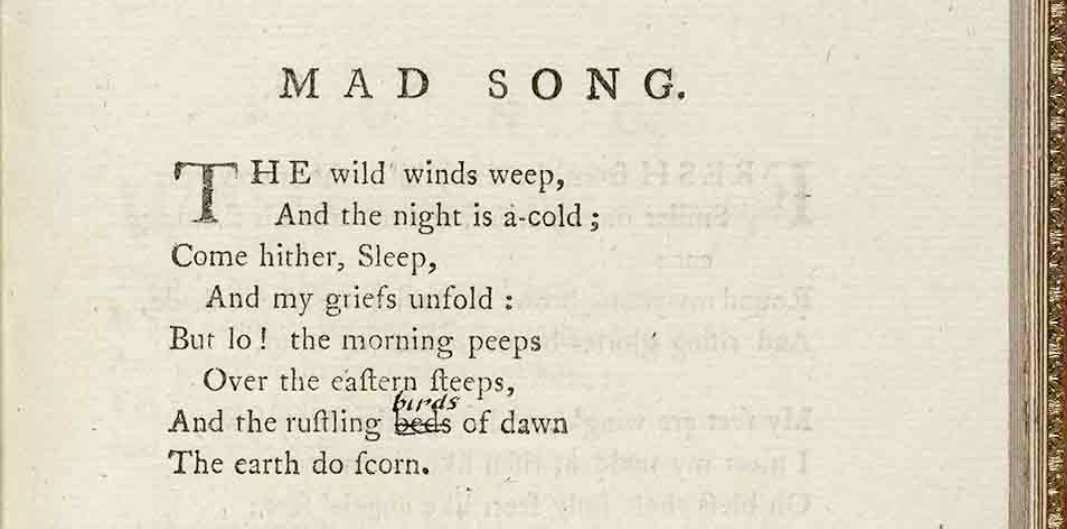

As you can see, Object 13 has been much less heavily revised than Object 3, the page that we’ve been focusing our initial encoding attempts on. However, it does have a section of vertical text on the right-hand side that seems to be connected to the body by means of a line. I was hoping that in addition to discussing the elements we have already developed (<stage>, <zone>, etc.) I could ask my instructors and coursemates about how to encode non-horizontal text and non-textual inscriptions.

However, before I could dive into these questions I was struck with A Great Insight: you can choose to approach your source material as a text or as a material object. (It really was an insight, too: one of those blinding flashes of sudden understanding that makes you feel like an idiot for not getting it before, but at the same time shows you why Archimedes was excited enough to leap out of his nice warm bath into the chilly air of his bathroom.) By approaching a source as a text, I mean that you would focus on encoding the actual content and structure of the writing on the page, such as stanzas, lines or metaphors. Approaching it as a material object on the other hand, would allow you to encode a physical description of information like hands or ink colour. The TEI guidelines includes modules for both methods – and more.

I realised that one of the difficulties in encoding the Four Zoas is that we want to combine both approaches: the textual aspects of the object are necessary for describing the words on the page in a literary way, while a material account provides the tools for talking about the revisions and compositional process that defines this work: indeed, The Blake Archive itself combines these two approaches. As we’ve discussed elsewhere, we’re not strictly TEI compliant, but are very much inspired by the structure and ethos of the guidelines and so thinking about a way of combining these two approaches in a thoughtful way became my primary objective while at DHSI.

I ended up creating two separate versions of my transcription of Object 13 – one textual and one material – that I hoped would show me what we would need to adopt from each approach. I’ll share these next week and talk more about my findings.

—