Transcribing Tiriel, Part II

In my earlier blog post on Tiriel, I discussed the issue of reading Blake’s hand with regard to the word “seald” in object 1. Here, I discuss another problem that I faced in transcribing this manuscript. Again, the reading that will be found on the Blake Archive is at odds with those of David Erdman and G. E. Bentley, Jr.

In object 10, line 25 of Tiriel, Blake first mentions the name of Tiriel’s youngest daughter. This name eventually evolves into “Hela” at the end of object 11. However, Blake originally had another name in mind, which he used in object 10 and in part of object 11, before going back and making emendations to that name. Blake’s (often inventive) names pose a problem– that examples such as those from my last blog post do not– in that textual context provides no clue as to what the word/name in question might be. Fortunately, in the case of the “Hela” problem, Blake writes the name several times (there are some instances in which an illegible name appears only once), giving the transcriber a variety of examples to examine.

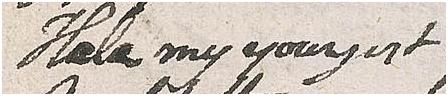

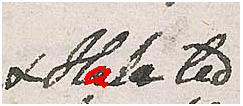

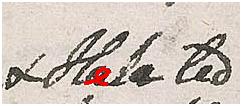

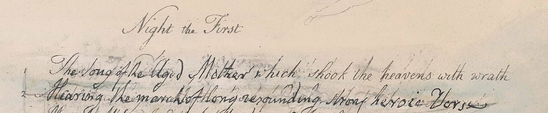

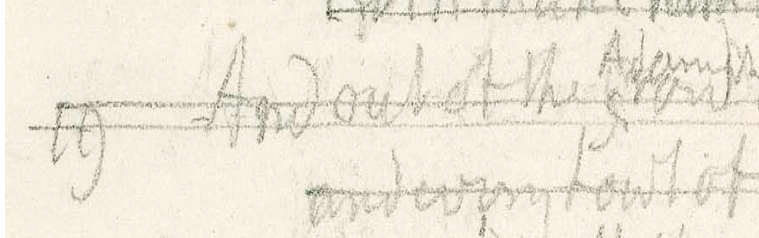

Here is an image of the name taken from object 10, line 25:

Erdman (in The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake) suggests that the name “Hela” was originally written as “Hili”, noting that “the first vowel is conjectural, but is not ‘e'” (815n). Bentley (in William Blake’s Writings) claims that the ‘e’ in “Hela” “is faulty, as if it were an ‘a’ which has been written over” (914n). He does not offer a reading of the final letter of the name, which Erdman correctly states is also mended. Presumably, Bentley reads the first version of the name as “Hala”.

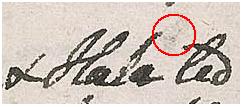

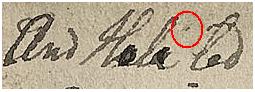

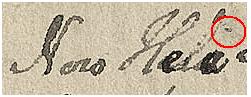

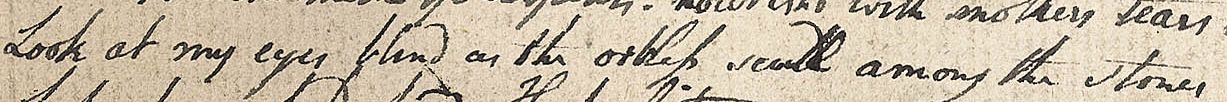

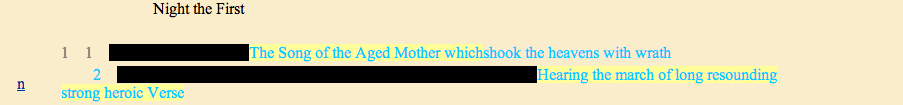

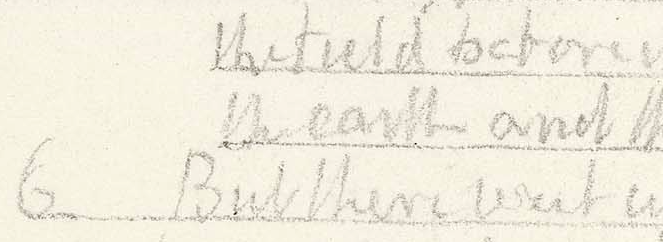

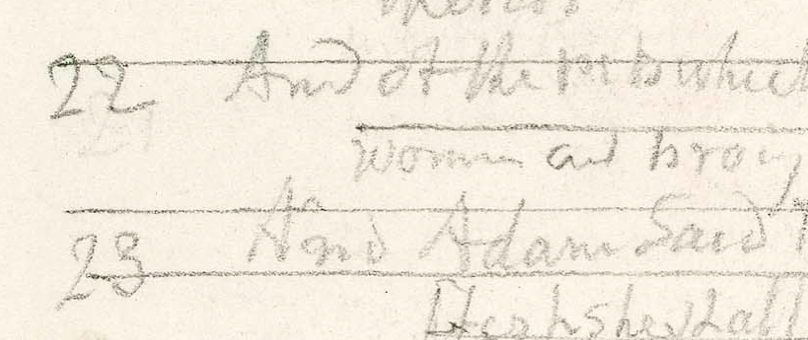

In reviewing objects 10 and 11 of the Tiriel manuscript, I came to favor a combination of Bentley’s and Erdman’s readings with regard to the initial version of “Hela”. I agree with Erdman that the last letter of the name—which is (contrary to Bentley’s description) clearly mended– was originally an “i”. If you look at the following samples (from 10.27, 11.2, 11.4, and 11.7) as well as that above, you can—in each instance– discern smudge marks above the final letter in the name:

These are the dots of “i”s that have been erased (with varying degrees of success) by rubbing. In fact, the dot in the third example above (from 11.4) is quite plain.

However, I do not agree with Erdman’s conjectural reading of the second letter of the initial version of the name as “i”. This is in part because the erasure marks that appear over the final letters in the examples above do not appear above the second letters. When I explained this reasoning to Rachel Lee, our Project Coordinator, she observed that the name may have been “Hili” and that Blake may not have dotted the first “i” because it would have interfered with the loop on the capital “H” preceding it. I shared Rachel’s concern because, in some cases—especially when a pen stroke from another letter (the cross stroke of a “t”, for example) occupies the space above an “i”—Blake will omit the dot. Therefore, I checked for instances of “i”s following capital “H”s elsewhere. In object 1, Blake writes “His” several times, dotting the “i” each time:

Therefore, “Hili” does not seem to be an accurate reading. Furthermore, based on the shape of the second letter in the name in the examples given, I believe that Bentley is correct when he suggests that the second letter in the name was originally an “a”. While the pen strokes in some of the examples above (such as 11.2) are not clear enough to provide a reading of the letter in question, others (particularly 10.27) are.

To better enable you to see my readings, in the first image, I traced the pen strokes making up the original letter, an “a”. In the second, I traced the emendation, an “e”.

Long story short, while Erdman reads the original version of “Hela” as “Hili” and Bentley reads “Hala”, I read “Hali”.

Continue reading