Xediting Blake’s Tiriel: How It Lives and What It Lives For

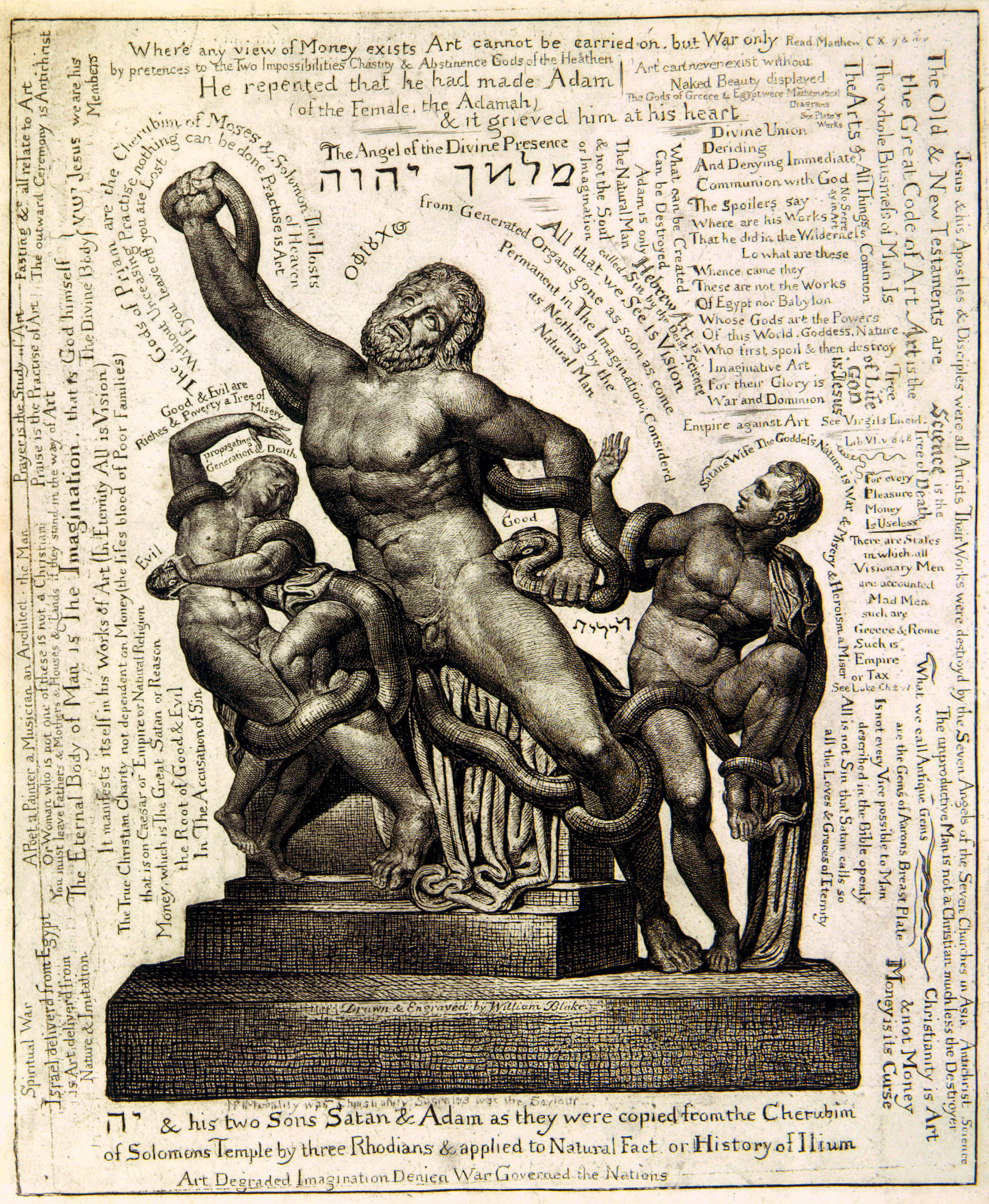

Blake’s Tiriel (?1789) comprises a manuscript of several pages plus several sketches and drawings—illustrations—more or less clearly related to the manuscript. Blake probably planned (originally) to engrave the writing and the illustrations or a selection of them and assemble the two in a set sequence—with or without a publisher (we don’t know)—not like the “illuminated books,” where text and illustrations are relief etched together on copperplates, printed, and often watercolored. But Blake never completed Tiriel, and the materials are now dispersed.

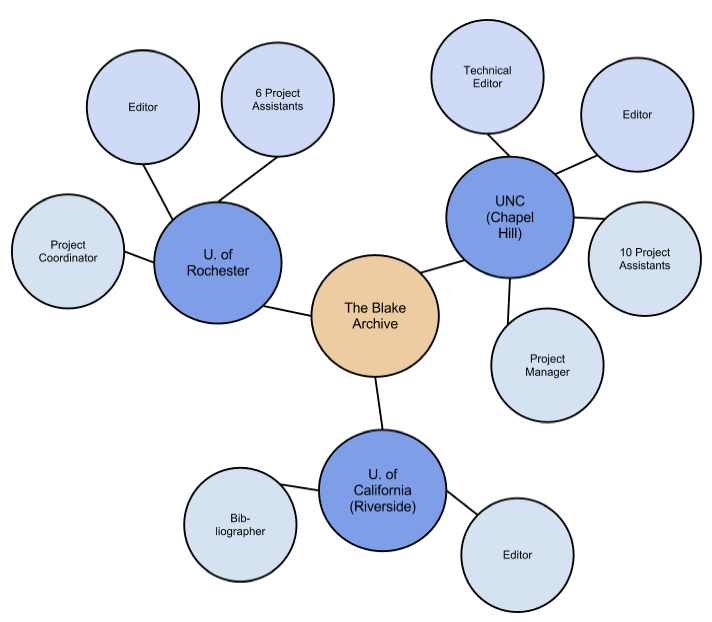

At the University of Rochester, the Blake Archive team (which at an early stage began to label itself BAND, for Blake Archive Northern Division) has the main responsibility for editing manuscripts and typographical works. But Blake being Blake, the separations between texts and pictures are often fraught with editorial difficulty. Recently we had a typical—for us, because we’ve been having these discussions since the early 1990s—discussion via email about how to present Tiriel in the Archive. We thought the discussion might interest at least five people in the world.

The players are (in order of appearance below):

Andrea Everett, editorial assistant, University of Rochester

Morris Eaves, co-editor, University of Rochester

Robert N. Essick, co-editor, University of California at Riverside

Joseph Viscomi, co-editor, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Ashley Reed, project manager of the Archive, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

and, offstage,

Rachel Lee, project coordinator for BAND, University of Rochester

On Aug 8, 2012, at 10:52 AM EDT, Andrea Everett wrote Morris Eaves:

I’m getting ready to pack my computer up, so I wanted to send you a short email about Tiriel before I shut everything down (you know, since I live in the Stone Age and don’t have internet access without my PC). I was wondering if it would be possible for Bob to set up the BAD [Blake Archive Description, or the Archive DTD; see Technical Summary in About the William Blake Archive, www.blakearchive.org) for Tiriel. Rachel [Lee, Project Coordinator, BAND [Blake Archive Northern Division]) and I spoke about it the night before last (you would have been proud of us–we were talking about the Archive at our farewell dinner), and we weren’t sure how the BAD would be set up, since the images for Tiriel seem to fall into a different category than the manuscript itself. They really don’t seem to be a unit, per se, in that the images could stand alone and are not an actual part of the manuscript. Would they need to be set up as a virtual group (like the illustrations and descriptions for L’Allegro and Il Penseroso)? I wanted to ask before setting up a BAD myself and finding out down the road that I made a faux pas.

2. On Aug 8, 2012, at 12:42 PM, Morris Eaves wrote:

Bob, what do you think? You may remember that we discussed the category question on blake-proj and decided that Tiriel belongs (basically) in manuscripts, though the drawings would be available as drawings in that category.

3. On Aug 8, 2012, at 4:28 PM, Robert Essick wrote:

Morris, I can’t recall ever creating a BAD file, from scratch, myself. Or, if I ever did, it was so long ago that I can’t recall doing it. The usual procedure is that Ashley [Reed, the Archive’s project manager at UNC/Chapel Hill) sets up the basic structure of the BAD file and I fill in the “mere content”—copy header information, etc. And I haven’t initiated any illus. markups in ages. Our usual procedure is to begin with Ashley and one of the assistants who writes the illus. descriptions. I then fill in the copy header, plus details in the so-called “plate header” such as objnotes [notes on individual objects, such as drawings], and correct the illustration descriptions. Could we follow this sort of procedure–or something close to it–for Tiriel? In any case, I think we need to consult with Ashley before doing anything else.

Yes, we should integrate the designs with the text, as well has including them under monochrome wash drawings in due course. I can imagine two ways of doing this–perhaps both:

•Link the entire group of drawings as one of the “Related Works” listed on the “work” page.

•Pick the individual pages of the MS that appear to contain the passages illustrated by the designs and link each off the appropriate OVP (Object View Page—the page where individual pages or plates or sheets are displayed) under “Related Works in the Archive.” Objnotes can be added to explain the relationship.

If we do the second, Ashley will have to set up the Related Works BAD, and add the proper coding to the BAD for the MS, as she has done in the past. Here again, this process is beyond my pay scale. In this case, I’m certain I’ve never done this myself (and when I recently made noises about trying it, Ashley told me to forgetaboutit).

On Aug 8, 2012, at 1:55 PM, Morris Eaves wrote:

Thanks very much for those thoughts, Bob. I guess we need to start with Ashley and go from there.

One question (for us) I guess is this: how unified a “work” do we want to consider/represent Tiriel as? A manuscript that happens to have drawings that seem to illustrate it? Or further down the road to One Work made up of text and drawings?

On Aug 8, 2012, at 5:18 PM, Robert Essick wrote:

I suppose that the distinction here, in terms of mode of presentation, would be between the MS with the designs linked through Related Works–or one integrated presentation with each design following the MS page with the passage illustrated. The latter gains support from the passage about such a work at the end of Island in the Moon [see Island object 17 in the Archive under Manuscripts], a model to which the Tiriel MS and designs (taken together) would seem to conform. That is, a letterpress or engraved text (based on Blake’s fair-copy MS) with quite a few high-finish engraved illustrations, full-page. The issue for me then becomes: do we represent this work (or works) in their present form, as separate entities (indeed, with the designs widely scattered among different owners), or do we want to try to realize what we imagine to be Blake’s “intentions” (I know, a dangerous concept) for the finished work? Now my caveat, or disagreement with myself. Such realized intentions would not be in the form of an MS with integrated wash drawings but a work in two different media, printed text and printed etchings/engravings. At no point in any production process that I can imagine, even if Blake had found a publisher or published himself, would the MS and the drawings be integrated into one work. Integration into a single work would only occur at the very end of the production stage, after printing. For an MS/drawings combo as the final product, one would have to imagine a one-off MS with illustrations suitable for presentation or sale to a single customer, not a published work in any form. That’s possible of course, but I can’t think of any clear evidence for such an “intention.” I suspect that when Tiriel left Blake’s hands, it was pretty much what we now have, except for the dispersal of the designs amongst multiple owners. If I’m right about that, I’d stick with two linked works, MS and designs, rather than an integrated combo of the two. Even if we are sure that’s what Blake intended, as his final Tiriel product, in *printed* form.

What am I missing here?

On Aug 8, 2012, at 2:39 PM, Viscomi, Joseph S wrote:

Last fall I worked out the economics of Tiriel and concluded that even with Blake’s engraving labor as gratis the project was too expensive and time consuming to do in its entirety, which is to say, had Blake intended to illustrated his MS after it was set in type (I worked out the number of pages this would be, which, if I recall, was fewer than the number of illustrations), he also intended to make a selection of his drawings for the work. Not all the drawings would have been engraved, not unlike the prepublication situation with The Grave and Night Thoughts [for which Blake did over 500 preliminary watercolor drawings]. So, what does that tell us? If we go by intention, we would have to make a selection, probably fewer than half executed, and I don’t see how we can do that. We can say here are the raw materials Blake was putting together in c. 1788-89 for an illustrated poem but put them aside as he began to see the possibilities of his new printing technique [i.e., illuminated printing] for both words and images and their various combinations on the same plates. He took some of Tiriel’s narrative and characters for [The Book of] Thel [an early illuminated book] and did not return to this earlier work, though he did indeed develop its theme of social or family dysfunction and explored further some of its social/psychological relationships.

On Aug 8, 2012, at 6:10 PM, Robert Essick wrote:

All good points Joe. Seems to me that what you say here argues for presenting the MS and the designs separately, with lots of links both ways, including the designs as Related Works in the Archive off the appropriate OVPs of the MS pages. Right?

On Aug 8, 2012, at 3:44 PM, Viscomi, Joseph S wrote:

Yes, that is what I meant to say, since we think we know his intentions while also knowing they are not realizable, since it involved a selection on criteria we cannot recover. In a way, linking to the pool of illustrations lets readers create their own illustrated Tiriel if they want to.

On Aug 8, 2012, at 7:10 PM, Robert Essick wrote:

I agree completely.

On Aug 9, 2012, at 8:53 AM, Morris Eaves wrote:

As much as I like the idea of your having calculated the economic unviability of Tiriel, Joe, I’m a little uneasy with the logic, if I understand it: that, because we might infer from a calculation of expenses that the (nonexistent) published version of a work would have to differ from the materials created pre-publication, as editors we should think (backwards) from the hypothetical publication-that-never-happened to the preliminary drafts (of texts and pictures) and, on that basis, separate texts from pictures in our presentation of the preliminary (never published) materials.

What is it about Tiriel that makes it different from other texts + illustrations (that exist in some state of pre-publication or non-publication tentativeness)?

On Aug 9, 2012, at 5:06 PM, Robert Essick wrote:

I basically agree with Joe on this Tiriel issue. I don’t think that the Tiriel MS and designs were ever integrated, interleaved, or joined together in any way. They would have been, presumably, in some finished production, but that never happened as far as we know. To integrate them into a single “work” might be an interesting project, but it would have to be recognized as some sort of modern production forged out of Blakean materials, not a work created by Blake as such–or even a sort of archaeological reconstruction of what we think Blake intended to do. I don’t think he ever intended to integrate MS and wash drawings into a single work using those specific media and materials. That would not be part of a production process leading to a printed work of some sort that would integrate words and pictures into an illustrated book like the 1808 Grave [by Robert Blair, illustrated by Blake, engraved by Schiavonetti]. This is quite different from the illuminated books, with words and pictures on the same supports, or the Night Thoughts watercolors with texts and illustrations pasted together to create single objects, or the Four Zoas MS with words and pictures on the same support. A very loose analogy might be with the 1805 Grave watercolors, intended as illustrations for a specific text but not integrated/interleaved with that text. It might be fun to create an illustrated edition of Blair’s Grave using all of Blake’s watercolors, but neither Blake nor Cromek [the publisher of The Grave] ever created such a work as far as we know. Text and designs only came together in the final, printed product of 1808 at the hands of a binder (or his collating assistant).

On Aug 9, 2012, at 5:35 PM, Viscomi, Joseph S wrote:

It would be interesting to know how Stothard and other illustrators worked; were they given exact instructions from the publisher to illustrate plates x, y, and z, or to find those passages that inspired them and then let the publisher or whoever is paying for it all to select what he liked. Did Blake choose what passages to illustrate for Wollstonecraft’s Original Stories? or did she or [the publisher Joseph] Johnson pick out the passages and assigned them to Blake? However they worked, providing more illustrations than needed or eventually used sounds reasonable, as does working with the idea that a selection by someone was part of the production process.

I like Bob’s conjectural Grave, with all 20 designs. Did Cromek request 20 designs or is that a sign of Blake’s energy and inspiration? Same with Night Thoughts. Did Edwards [the publisher] ask for 537 designs or was this just Blake being Blake, producing far more than could ever be engraved?

On Aug 9, 2012 at 6:16 PM EDT, Morris Eaves wrote:

I suggest that the primary editorial question isn’t about how we might reconstruct (or not) some hypothetical production process leading (or not) to a published work. Nor is it about analogies with, say, the Grave illustrations, which are illustrations to someone else’s text that already exists. In that case Blake is contributing illustrations.

But the strictly editorial question is, anyway, not about the unknowable future that Tiriel never had but about the pile of related materials we do have–raw materials of various kinds for . . . something.

How, that is, do we present a “manuscript” that’s made of related but discrete pieces, some textual and some visual/imagistic, whose exact connection we don’t/can’t know. But is that not like a novel that’s been written in various pieces that constitute a pile of a draft that the novelist doesn’t know how s/he will eventually put together? And no doubt throw some of it away as superflous, or redundant, or whatever.

Now if you are sure that the two were not being made together as an illustrated work, or call it an illustrated text, then I can see why we’d want to put the two in two utterly different piles/closets of the Archive, Tiriel the Manuscript and Tiriel the Illustrations. But if they were part of the same project, being created together, and they’ve been subsequently dispersed, I’m wondering if we really want to so casually split them up. And then splice them together, sort of, with the means at our command, like Related Works, etc.

I’m not doubting that we want the textual manuscript and the drawings manuscripts (let’s call them) to appear in both compartments of the Archive—manuscripts and drawings—but I’m wondering if we want to assert editorially, in effect, that they belong to two different Tiriels.

Question: IF we had them in Blake’s order (his little piles of rough drafts, in effect), would we split them into two halves because they’re in different media? Are we separating them only because history has separated them and we’re simply comfortable with that text/image separation? To put it another way: if these pieces were all textual pieces (with no images, but also with no numbering or other sequencing that would tell us how to arrange this object Tiriel, would we put these separate hunks of text under one textual roof called Tiriel in the Archive or would we split them up under various textual roofs because Blake hadn’t passed along the continuity we need to arrange them in sequence? In that case we wouldn’t know what order to put the textual pieces in. So what would we do?

I’m as comfortable as you two are with the text/image separation–but I’m pretty sure that it’s that very text/image separation that makes me so comfortable. Just saying . . . .

PS I promise not to carry on about this forever.

On Aug 9, 2012, at 8:42 PM, Robert Essick wrote:

I’ve been trying to think of all the alternative ways we could present Tiriel, text and designs, regardless of the arguments about the nature of the work(s), production history, subsequent history, media, etc. So, far, I’ve been able to come up with only three (limited imagination very probably):

1. A single, integrated “work,” with each design following the MS page on which the passage illustrated appears.

2. The MS followed by all the illustrations, the latter in the sequence we think follows the passages illustrated. Presented as a single “work.”

3. The MS as a single work, the designs as a single work, with multiple links in both directions, including links to each design off the OVP for the MS page we think contains the passage illustrated by a design.

4. ???

I think that Joe and I have been arguing for number 3. Number 2 is OK with me; the two media (MS, wash drawings) may have been side by side, as it were, on Blake’s work table. They are, indeed, part of the same project. Thus, possibly a compromise position?

I’m slightly uncomfortable with no. 1 because it creates a single, integrated work that I don’t think ever existed. Not from the very get-go, not ever–until we produce such a “work.” But, even if we adopted no. 1, I can still hold to my ideas about the production history of Tiriel.

My sense of these alternative modes of presentation has absolutely nothing to do with the history of the text and designs after they left Blake’s hands. Nothing. Really. I promise. My slight discomfort with no. 1 is based on my sense of how the pieces were produced, from the very start, and how they remained spatially separate (not integrated, leaf by leaf, MS and designs collated together) while in Blake’s hands.

I suspect that Blake wrote the text of Tiriel (although perhaps not the fair copy we now have) before he executed the illustrations. Or at least composed the part of the text illustrated by a design before executing the design. OK, just another former English professor assuming the primacy of language over pictures. But hard for me to imagine a production scenario in which Blake executed finished monochrome washes, then wrote a poem to go with them. Thus, the text came before the designs, just as in my loose analogy with the Blair illustrations. The fact that another poet wrote the text in one case, and the same fellow write the poem and executed the designs in the other, doesn’t change my sense of the production sequence.

I’m done. Whatever the other BlakeBoys decide is fine with me.

On Aug 10, 2012, at 12:40 PM, Morris Eaves wrote:

This sounds very reasonable (and true) to me: that the work evolved as a single work, or single enterprise–comprising text + illustrations in some fashion that Blake probably never arrived at final decisions about—in a way that, editorially, is approximated best by one assemblage in, as it were, 2 parts:

2. The MS followed by all the illustrations, the latter in the sequence we think follows the passages illustrated. Presented as a single “work.”

To my mind, other presentations–like texts under Manuscripts and drawings under Drawings–reproduce too harshly the division that we invented the Archive, at least partly, to avoid.

But, should we go that way (#2), of course we’d want the drawings to show up as drawings in that category as well.

On Aug 11, 2012, at 6:57 AM, Robert Essick wrote:

That’s fine with me. Makes constructing the BAD easier I believe, although we still need some input from Ashley to set up its basic structure. An assistant at UNC can draft the illus. descriptions (which I will check), the Rochester team can fill in the transcription, and either the Rochester team or I can write the copyreader (if the Rochester teams gives this a try, I can of course check it over). I already have a number of objnotes rumbling through my head.

Joe, what do you think?

On Aug 11, 2012, at 6:56 AM, Viscomi, Joseph S wrote:

Bob, I agree with your comments below, i.e., there is little difference between Blake illustrating a text of his own or of another writer, in terms of production, and that text probably generated the illustrations (though I don’t have much of a problem of imagining images generating text, as they do for my own writing on Blake; think Hogarthian narratives over 12 plates that function aesthetically autonomously as well as part of something verbal)

Anyway, I am okay with number 2, which I see as providing all the raw materials done for the same project, with an admission in our introduction that these pieces were not put together and no plan exists revealing Blake’s intentions.

On Aug 11, 2012, at 10:09 AM, Robert Essick wrote:

Good Joe; I think we are all agreed on option number 2 now. Next step, I believe, is for Morris (or others at Rochester) to contact Ashley about setting up the BAD (skeletal form–content to come later) and decide on who will do the first-round of illus. markup (you know who will do the second round).

On Aug 12, 2012, at 5:13 PM EDT, Morris Eaves wrote:

Ok, great–so we can take the next step (we, I mean Ashley), which will allow Andrea Everett to get started on the transcription. At least we’ve now got a starting place. I’ll compile our thoughts and write Ashley, and she can get to the BAD whenever it fits into her schedule.

On Aug 12, 2012, at 5:18 PM EDT, Morris Eaves wrote:

Andrea and Ashley, if you read this compilation, you’ll see the conclusion we’ve reached through strenuous discussion. But we do actually come to a conclusion; just don’t hold your breath.

Bottom line: it should give Ashley the info she need to create a BAD or BADs, or whatever is needed to create a foundation for Andrea’s work on Tiriel. Thanks to you both for your patience and endurance in reading through this stuff. But I do think you’ll find the discussion interesting enough to warrant reading it.

PS: I’ll also copy Rachel [Lee] so she’ll be in the loop.

On Aug 13, 2012, at 12:07 EDT, Ashley Reed wrote:

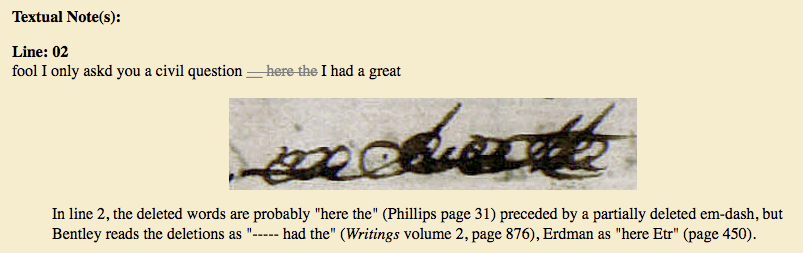

Hi, Morris. This sounds fine to me (and it was fascinating reading through the decision making process). What I’ll have to do is make separate BADs for the manuscript and the drawings (the Archive’s programming maintains the rigid distinctions between media even when we don’t want to) and then use virtual groups to combine them (as we did with L’Allegro & Il Penseroso). Before I can do that, though, I have a couple of questions:

1) On the tracking sheets the object numbers for the Tiriel manuscript start at 3 and go through 17. Bentley lists the object order as simply 1-15. Are we missing two pages, or should these just be renumbered 1-15?

2) I have an email from Andrea from August 1st where she says we have the following drawings:

Plate I. Tiriel Supporting Myratana (Drawing no. 1) [we also have 2 preliminary sketches for this piece]

Plate II. Har and Heva Bathing (Drawing no. 2)

Plate III. Har Blessing Tiriel (Drawing no. 4)

Plate IV. Tiriel Leaving Har and Heva (Drawing no. 6)

Plate V. Tiriel Carried by Ijim (Drawing no. 7)

Plate VI. Tiriel Denouncing His Four Sons and Five Daughters (Drawing no. 8) [we also have 2 preliminary sketches for this piece]

Plate VIII. Har and Heva Asleep (Drawing no. 11)

But the tracking sheets don’t list Plate VI / Drawing no 8. Andrea, where did you see that drawing?

And so it goes on. . . .

Continue reading