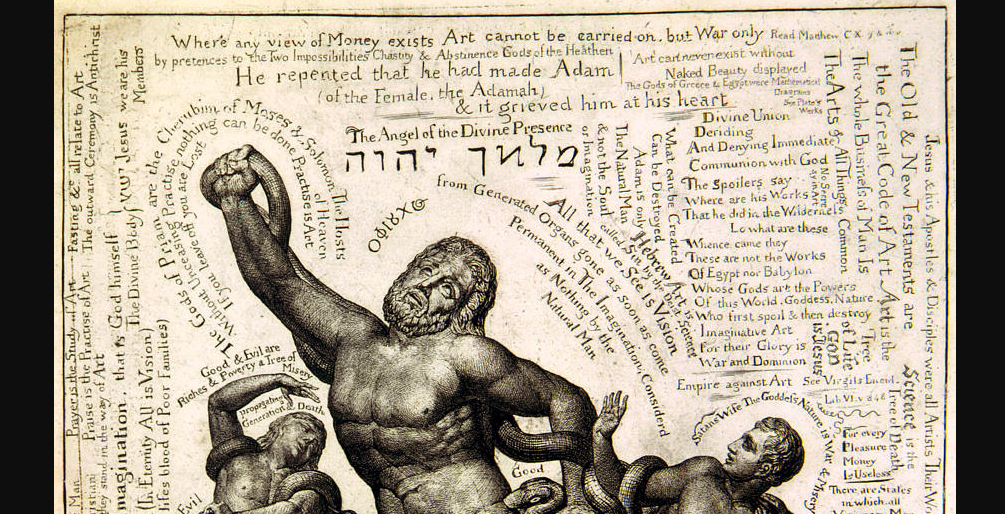

One of the first blog posts I ever wrote for Hell’s Printing Press was titled “Laocoön and Languages.” The inspiration behind the post was that, in working on textual transcriptions, I had come across instances where Blake writes in a language other than English and I had been pointed to Laocoön as an example of a published Blake Archive work that deals with the problem of how to transcribe text in languages other than English.

Basically, my object in writing that post was to answer the question, if Laocoön is the standard precedent for how to transcribe foreign language text, what are the protocols for doing so? I made some observations based on what I saw in Laocoön and put these findings into the form of a loose set of instructions.

That was nearly four years ago. As often happens with the Archive, the range of editorial questions continues to grow. Here I want to address some of the more interesting challenges that have come up in relation to the transcription of text in languages other than English.

1) Letters or Entity Codes?

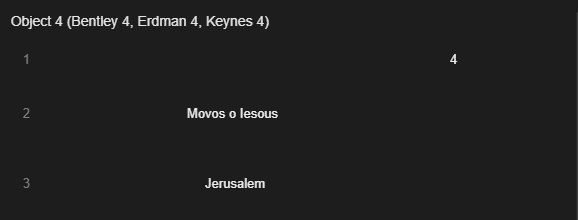

It seems that at one point in the history of the Archive, the practice for certain Greek words may have been to just type out the word replacing the Greek letters with similar looking Latin alphabet letters.

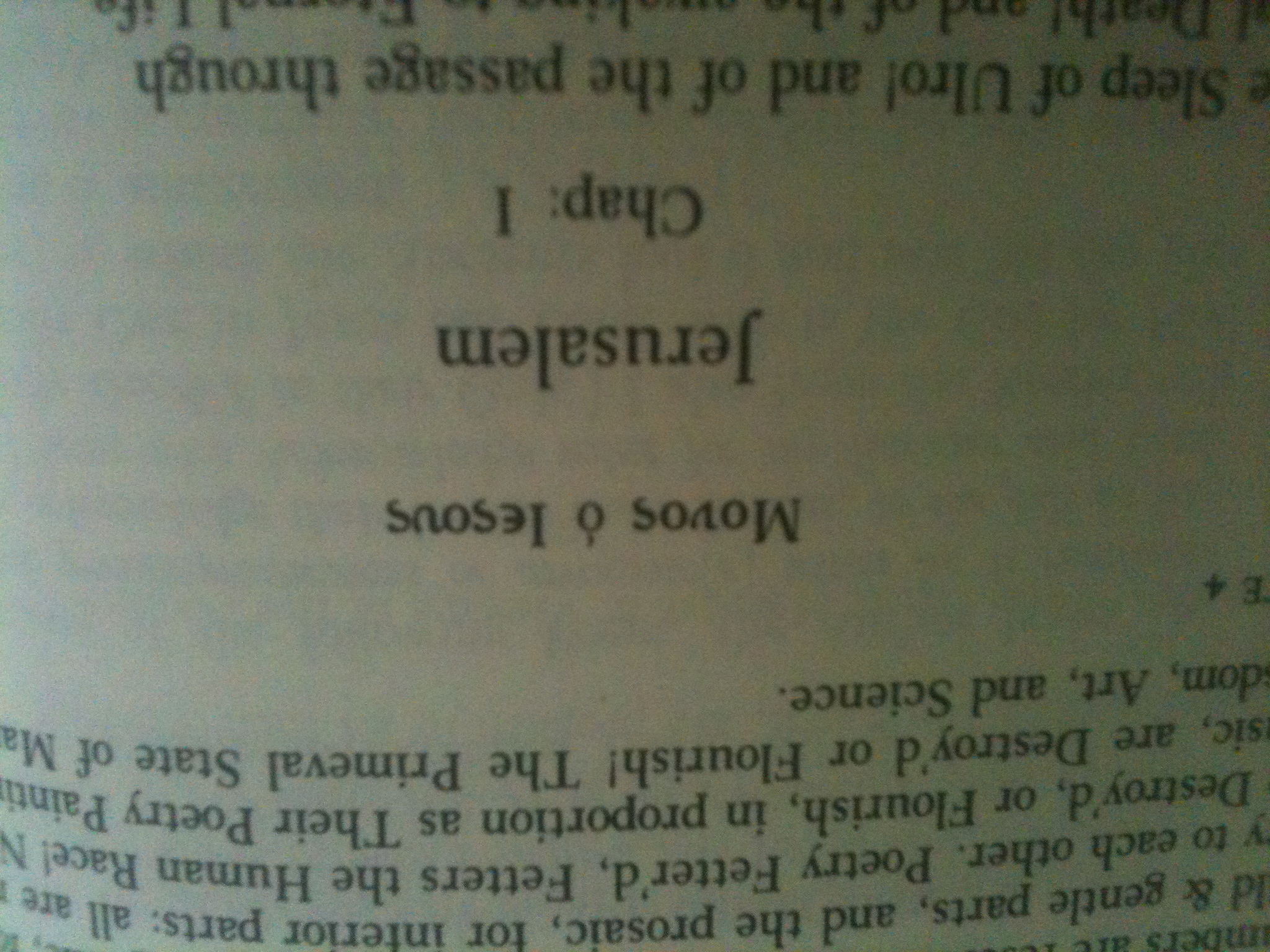

Hence, in Object 4 of Jerusalem, Μονος ό Ιεςους becomes “Movos o lesous.”

With more recent works we make more of an effort to emulate these words as we see them.

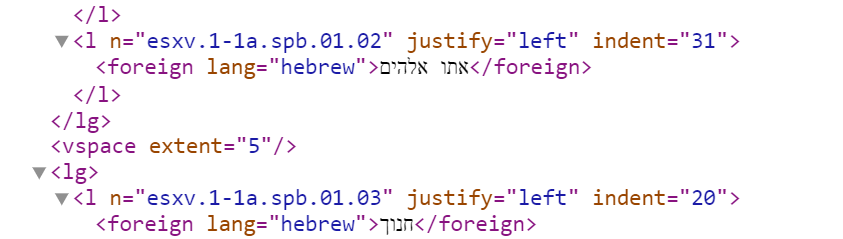

In XML there are entity codes for letters in alphabets other than the Latin alphabet, just like there are entity codes for ampersands, dollar signs, and em-dashes. However, the reason why we use entity codes for those things is that typing in an ampersand, for example, will not work in XML; it creates an error. Non-Latin alphabet letters on the other hand will display. So is there any point to using entity codes as opposed to typing (or copy and pasting) in the actual letters?

The textual transcription displayed on the screen will look the same to users of the Archive regardless of which one we use. The only way they would know which one we’re using is if they view the XML, but as with most things we do, consistency to the extent that it is possible is a good goal.

In the published works I’ve looked at, it seems that the precedent is to use letters rather than entity codes and it obviously works fine as far as display is concerned.

2) Knowledge Deficiencies

Not long ago, I was working on a transcription that involved a lot of Greek words, and decided to enter the characters by going to a website that would allow me to type these letters and typing, copying, and pasting each word as needed. It seemed mostly straightforward. But then I realized I had no idea what this was:

None of the Greek letters on the keyboard I was looking at looked anything like it, and nobody working for the Archive seemed to have enough knowledge of Greek to help me out.

Fortunately there is a classicist at University of Rochester who was nice enough to shed some light on the mystery when I emailed him about it. Apparently the reason I couldn’t figure out what letter this was is because it isn’t a letter; it’s what is known as a “ligature,” (or a combination) of omicron and upsilon (ου), in the same way that æ is a ligature of “a” and “e.”

As far as I could tell, there did not seem to be an entity code for this ligature as there is for æ, so likely when transcribing it we would just transcribe it as ου, rather than trying to reproduce the ligature.

In principle it’s a little bit like our policy on old typography. When transcribing typographic works, we don’t reproduce the old eighteenth century “long-s.” Then again, with ligatures we’re in a somewhat more complicated position, because it would seem that we do reproduce some ligatures. It will be something to keep in mind going forward.

But the broader lesson to take away from this experience was, “Ask. Don’t guess!” Whether using entity codes or typing out the letters, it’s important to get the letters exactly right. Otherwise, why not just do them all like the words on Object 4 of Jerusalem? The Hebrew and Greek alphabets are very complicated so when working on an object that contains words in these alphabets it’s important to realize when to ask around for assistance.

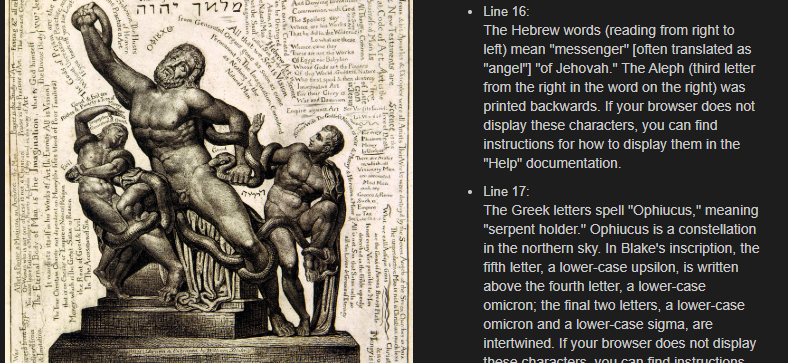

3) Blake’s Innovation

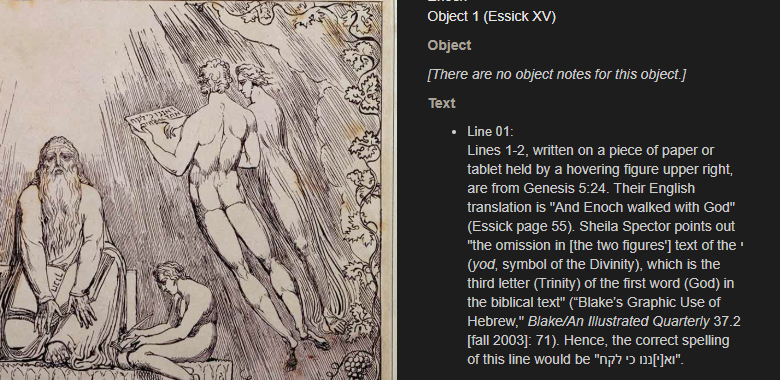

Blake made languages and alphabets his own. As Abraham Samuel Shiff pointed out to me last time I blogged on this topic, Blake did not always write letters the “correct” way (check out Shiff’s Blake Quarterly article on this topic here). He also spelled Hebrew words unconventionally, as he sometimes did with English words.

The principle for these situations seems to be to do the best we can to replicate the text we see on the object and articulate the rest through object notes.

We’ve clearly come a long way from “Movos o lesous.” But Blake’s use of foreign languages and his own creative twists on them will likely continue to present interesting editorial puzzles. The best way forward for us as editors is to stay humble, keep learning, and try to enjoy the kind of surprises that always seem to be right around the corner when transcribing Blake.