The William Blake Archive is pleased to announce the publication of a digital edition of Blake’s French Revolution.

The French Revolution (1791) is the only one of Blake’s works of poetry ever slated for conventional publication—and by England’s most prominent publisher of reformers and radicals, Joseph Johnson, whose authors included, among others, Erasmus Darwin, Mary Wollstonecraft, William Godwin, Joseph Priestley, and Thomas Malthus. But Blake’s poem falls into a sadly familiar pattern in his artistic life: promises made, projects curtailed or cancelled, hopes dashed. The French Revolution, A Poem. In Seven Books. Book the First is followed by an optimistic “Advertisement / The remaining Books of this Poem are finished and will be published in their Order.” If books 2-7 did exist, they never progressed beyond a manuscript now lost, any more than the great illuminated book Milton / a Poem in [1]2 Books ever got beyond its first two.

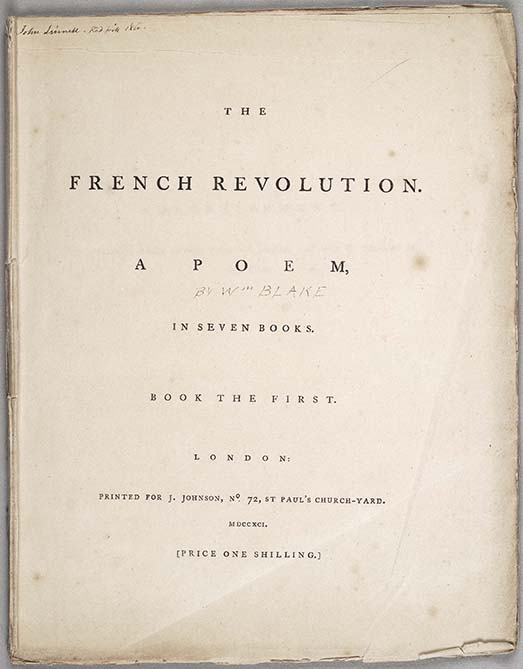

Only one copy of The French Revolution exists, apparently page proofs (set in type and arranged in pages for final stages of proofreading before publication). Blake’s name does not appear. “Wm Blake” is inserted in an unknown hand in the customary space for authors’ names. The original anonymity was perhaps an error but more likely a consequence of the same reticence to be identified with overtly radical sentiments that Blake showed on other occasions—in 1790, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (closing with the chorus of “A Song of Liberty”), is the only illuminated book neither signed nor dated. If The French Revolution was withdrawn from publication, why? Johnson withdrew Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man the same year; perhaps he abandoned Blake’s poem for similar reasons. Concern would not have been entirely misplaced: in 1799 Johnson spent six months in prison for seditious libel.

Blake eventually gave, or sold, the page proofs of The French Revolution Book the First to his friend and patron John Linnell. A posthumous excerpt almost made it into W. M. Rossetti’s selections from Blake’s work for the 1880 edition of Gilchrist’s Life of Blake—but not quite. Not until 1913 was Blake’s poem finally published, in the second edition of John Sampson’s Poetical Works of William Blake, well over a century after its original retraction.

Its date and subject mark The French Revolution as an attempted poetic contribution to the fierce Revolution Controversy, associated especially with Richard Price’s sermon and pamphlet, “Discourse on the Love of Our Country” (1789), Edmund Burke’s widely read Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790), and Paine’s Rights of Man (1791, also printed for Johnson but published by someone less cautious).

In his edition, Erdman places The French Revolution in the category of Prophetic Works, Unengraved. “Prophetic” puts it where it belongs, with early works such as Tiriel (1789), The Book of Thel (1789), and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790)—all experiments in mythmaking whose tone and meaning can be so elusive. The French Revolution is the most explicitly historical of the early group—with characters (Fayette, the King), settings (the Bastille, Versailles), and plot elements transplanted from the daily news into mythic narrative that portends apocalyptic change:

Sick, sick: the Prince on his couch, wreath’d in dim

And appalling mist; . . . from his shoulder down the bone

Runs aching cold into the scepter too heavy for mortal grasp . . . .

. . . Rise, Necker: the ancient dawn calls us

To awake from slumbers of five thousand years

(Erdman page 286)

Historically, the plot compresses the earliest stage of the revolution—May to July 1789—into a single hypercharged sequence, from dawn to dawn, with suggestions of psychomachia, a psychological struggle against a radical change of mind. For his mode of telling, Blake searches again—as he had in Tiriel and Thel—for a poetic line capable of containing such volatile elements. The meter of The French Revolution has been characterized as “a consistently anapestic roll” (Frye, Fearful Symmetry page 185) and “anapestic-iambic septenary” (Damon, Blake Dictionary page 146), but it may be more helpful to hear it in the broad context of experiments in the long heroic line that start with Tiriel and Thel and culminate in the encyclopedic mythopoeia of The Four Zoas, Milton, and Jerusalem.

As always, the William Blake Archive is a free site, imposing no access restrictions and charging no subscription fees. The site is made possible by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with the University of Rochester, the continuing support of the Library of Congress, and the cooperation of the international array of libraries and museums that have generously given us permission to reproduce works from their collections in the Archive.

Morris Eaves, Robert N. Essick, and Joseph Viscomi, editors

Joseph Fletcher, managing editor, Michael Fox, assistant editor

The William Blake Archive