The William Blake Archive is pleased to announce the publication of digital editions of our third installment of Blake’s 95 known letters. The latest 28, drawn from nine collections, span nearly the entire chronological range of Blake’s correspondence from 1791 to 1827, the year of his death. Three of this group are by Blake’s correspondents—included here because of especially tight connections with their associated documents. (Those pairs are 18 October [Reveley] and October 1791 [Blake]; 23 September [Blake] & September 1800 [Butts]; 18 December [Cumberland] and 19 December 1808 [Blake].)

A sample of the many highlights from the 28 new letters might feature

—2 October 1800 (to Blake’s London patron Thomas Butts): fresh with optimism after his recent arrival in Felpham, Blake’s awkward amalgam of down to earth excuse-making with 78 lines of visionary verses:

To my Friend Butts I write

My First Vision of Light

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I saw you and your wife

By the fountains of Life

Such the Vision to me

Appeard on the Sea

Mrs Butts will I hope Excuse my not having finishd the Portrait.

—16 August 1803 (to Thomas Butts): Blake’s “whole outline” of his dangerous and distressing encounter with the soldier Private John Scolfield in Blake’s garden, which resulted in a “very unwarrantable warrant,” a charge of sedition against Blake, depositions, a lawyer, a trial, and, finally, acquittal: a “perilous adventure” for sure. Its imaginative afterlife was the appearance of Scolfield and his companion Private John Cock as shady Sons of Albion in Blake’s illuminated epic Jerusalem.

—18 January 1808 (to Ozias Humphry): Blake’s detailed description of his intricate 1808 watercolor Vision of the Last Judgment (Petworth House, Sussex), commissioned by the Countess of Egremont on Humphry’s recommendation. (We reproduce one of the three copies that Blake made of his description; see Bentley, Records, pages 249-50.)

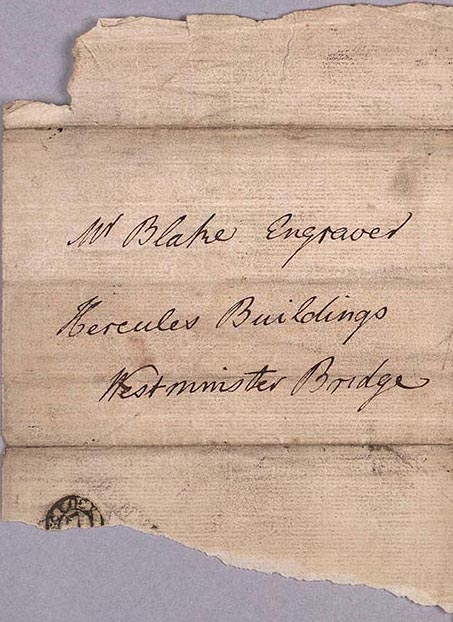

—25 November 1825 (to John Linnell): sometimes called the kitchen letter for Blake’s brief contention that his flat at 3 Fountain Court would be the optimal place (the press is already assembled there, the lighting is better) for printing a copy of his engraved Illustrations of the Book of Job. For details of the unearthing of the letter—which turned up in a box of autograph scraps in the archives of publisher John Murray—and its surprisingly rich contexts in Blake’s workaday life, see Angus Whitehead, “The Uncollected Letters of William Blake,” Huntington Library Quarterly 80.3: 423-35.

Blake traveled seldom and not very far. His circle of correspondents was narrow and the geographical circuit small. But his modest body of correspondence comprises an absorbing, revealing miscellany of reports on work in progress alongside friendly and not so friendly exchanges on matters of practical and intellectual substance. Occasionally the letters burst out into visions that amalgamate, in a characteristic Blakean vein, homely details, intensely energized prose, and inspired poetry.

The letters are, in any case, indispensable in preserving facts and contexts for his life and work that would be otherwise unknown and in showing him shift pragmatically from role to role in a very natural—and human—way, exposing facets of character and personality not always so apparent in his art. The letters feel closer to the exigencies of everyday life than any other works from Blake’s hand. He seldom puts pen to paper without interesting consequences for readers.

Once again, special thanks to the City of Westminster Archives Centre for courteous assistance, excellent digital images, and willingness to share Kerrison Preston’s Blake library with the world.

As always, the William Blake Archive is a free site, imposing no access restrictions and charging no subscription fees. The site is made possible by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with the University of Rochester, the continuing support of the Library of Congress, and the cooperation of the international array of libraries and museums that have generously given us permission to reproduce works from their collections in the Archive.

Morris Eaves, Robert N. Essick, and Joseph Viscomi, editors

Joseph Fletcher, managing editor, Michael Fox, assistant editor

The William Blake Archive