As I anticipated, the Blake Archive has woven its way into my graduate curriculum. This semester, Blake and his writings arrived via “Radical Romantic Critical Theory,” a graduate seminar taught by Blake editor Morris Eaves.

Each week, we are tasked with responding to a prompt Morris posts digitally, aiming to engage with the week’s assigned texts, but often more importantly, with each other. After having discussed the poetic philosophies of Alexander Pope and William Wordsworth, it came time to [constructively] duke it out over what William Blake’s writings meant for his philosophy of art.

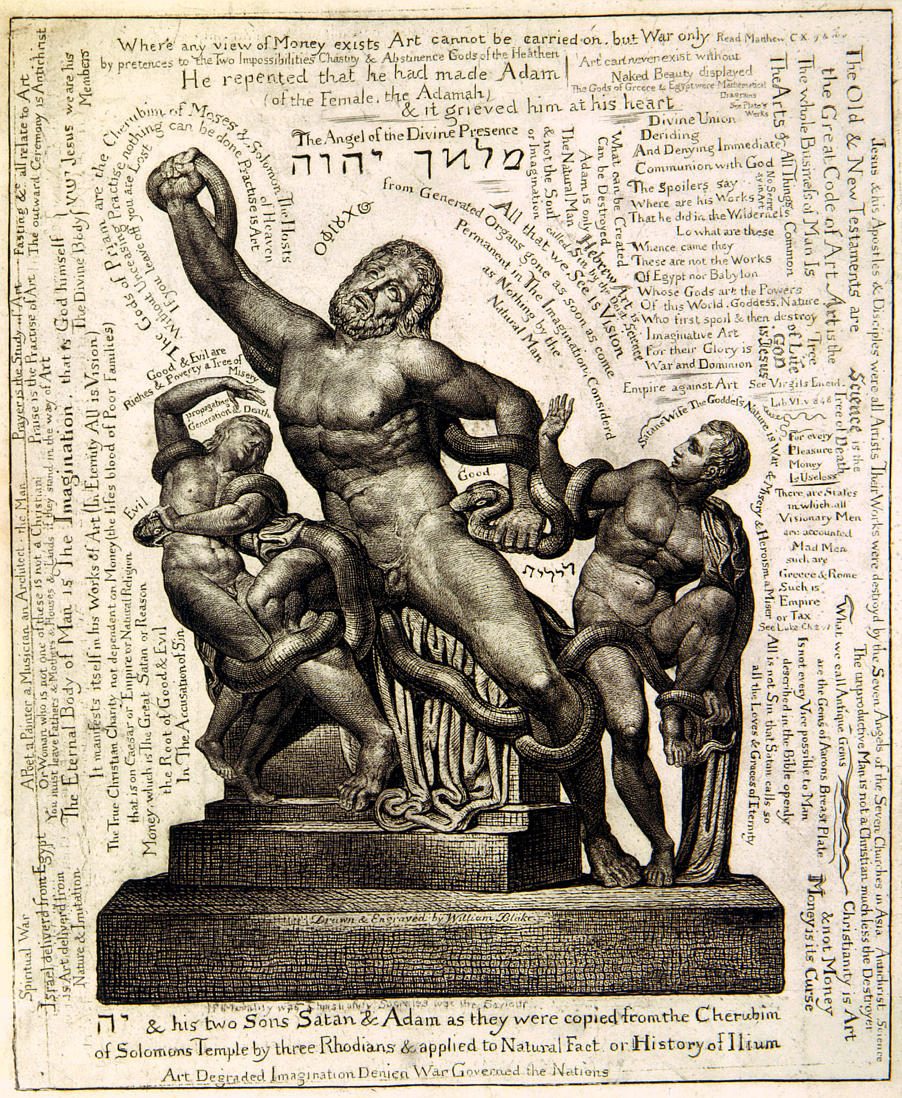

Laocoön Copy B , one of the texts our class was tasked with responding to

Using Blake’s “Public Address,” “Prospectus of 1793,” and engraving of Laocoön (pictured above) Morris asked us to focus on what the works suggested about Blake’s idea of the Artist, their Art, and their Audience. Here’s a few excerpts of what some of my classmates came up with:

One student focused on the importance of precisely rendering an idea:

“For Blake, there is no independent idea that precedes the execution of it. The techniques of execution are not only a separate set of means, they can fundamentally change the message of the art work. Therefore, not only should the idea expressed through the art work be integral and spontaneous, the execution of the idea should also strictly accord to such spirit. This also helps me understand Blake’s emphasis on accuracy—if the art work is an organic whole, then any minute alteration will influence the whole.”

Another student contemplated the Artist’s presence in their Art:

“In Public Address, Blake writes: ‘Character & Expression can only be Expressed by those who Feel Them’ (Erdman, 568). I interpret this as the work of art is true only if the character of the artwork becomes appropriate to the identity of the artist.”

Another considered Blake and the market’s relationship:

“This seems to cause some anxiety in Blake, who is straddling the inner world of visions and inspiration and the definitely external-from-Blake wishes and wants of the masses. It’s not that Blake is upset with his imagined audiences, for in the Prospectus he recognizes that ‘The Labours of the Artist, the Poet, the Musician, have been proverbially attended by poverty and obscurity; this was never the fault of the Public, but was owing to a neglect of means to propagate such works as have wholly absorbed the Man of Genius.’ (Prospectus, Erdman 692). Blake’s just looking for a way to unite audiences’ tastes with what he sees as the true source of art.”

And after describing their findings in each piece, one student concluded, in a way I don’t think Blake would disagree with, that

“The artist [is] an innately divine imaginative genius who creates something new and unique from the combination of what exists and gives new life to art.”

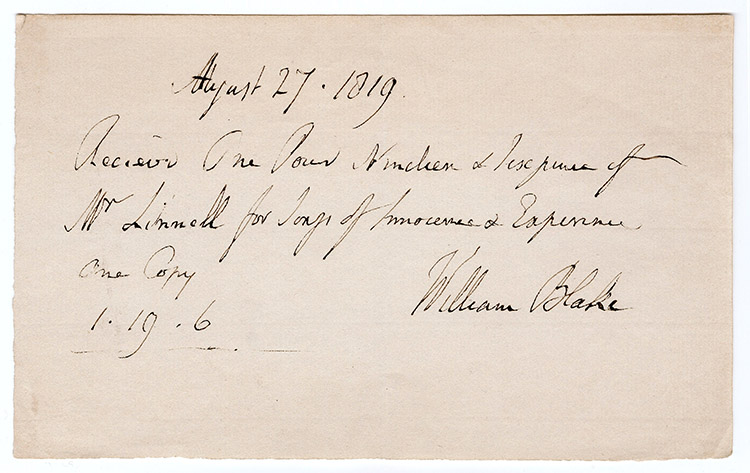

Having recently emerged from the depths of Blake’s recently Archive-published receipts, it was refreshing for me to see a different side of Blake; after all, since I joined the Archive this last semester, the receipts had me focusing solely on the business side of Blake’s artistry. There, I was more immersed in his bookkeeping, gaining only brief allusions to his genius via recorded transactions of works like Songs of Innocence and Experience, as pictured below.

Through the class discussion, my classmates and I grappled with what seemed more Blakean in spirit— his status as an Artist, his views of Art, and his often tense relationship with his audience— and as excerpted here, those writings provided a host of starting points for interpreting these philosophies. It seemed that as capable as Blake was of “giving new life to art,” our beloved “innately divine imaginative genius” was just as capable of giving new life to discussions of his process, his self-expression, and his views of popular opinion.

That being said, these writings have provided just as much fodder for seminar discussions as they have for broader considerations of the status of the Artist, their Art, and their Audience. In a very TED Talk-ian way, they prompt us to consider: how many of his thoughts expressed in the “Prospectus of 1793” or the “Public Address” remain relevant today? How much has been remedied or worsened? Are artists still “innately divine imaginative genius[es]” or has something gone afoul since the late eighteenth century?

Whether you want to ponder his finances, his artistry, or his philosophical implications, Blake— as per usual—has given us a lot to think about. Fortunately, I hear there’s quite the group of people who just might be interested in such a discussion.