Day of DH 2014

Welcome to BAND’s 2014 Day of DH post where we answer the question, “just what do digital humanists do?”

Continue readingTag

Welcome to BAND’s 2014 Day of DH post where we answer the question, “just what do digital humanists do?”

Continue readingThis coming Tuesday (8 April 2014) Team Blake Archive will be participating in Day of DH, an open community publication project for those interested and working in the digital humanities. The idea is to provide some answers to the question, “Just what do digital humanists really do?” by creating a snapshot of everyday life in the world of DH. Along with many others across the world, we will be documenting our day and posting the results on the blog and here.

Continue readingWe’re excited to announce that the William Blake Archive has [finally] arrived on Twitter. You can find and tweet us using @BlakeArchive.

Continue readingBy Megan Wilson

Like Margaret, I am an undergraduate at the William Blake Archive with the University of Rochester (BAND). I must commend Margaret on her spot on description of what it is like to work at the Blake Archive.

Continue readingThis past week in Charlottesville, I had the opportunity to attend two events hosted by the Association for Documentary Editing (ADE). The first of these was “camp edit,” or the Institute for Editing Historical Documents. In a week of seminars we covered a range of editing and publishing topics, from transcription, document search, and annotation to project management, modes of publication, and fundraising. I was glad to find this year’s program emphasized questions raised by digital technologies in addition to its core curriculum of transcription, annotation, proofing, indexing, project management, and publication. A session on digital tools for editing led by Andy Jewell, of the Willa Cather Archive and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, was supplemented by conversations linking traditional scholarly editing topics to some of Andy’s experiences in the digital realm at UNL and before that with the Whitman Archive.

Some topics from the old core curriculum appeared less relevant to our work at the Blake Archive at first, but I found many underlying principles could inform our own practices, even where the means may be quite different. For example, during the session on indexing led by William Ferraro of the George Washington papers, I wasn’t sure that I would gain much practical knowledge as an assistant to a digital project without a traditional book index. As the seminar continued, however, I found myself thinking of indexing less as a way to direct users to specific pages in a book and more as a practice in the kind of constrained vocabulary description and document linking that power the searching, browsing, and sorting within a digital edition. We may have more options for how we structure those connections in a digital edition, but there is no less of a premium on transparency, usefulness, and efficiency for users in the way we structure relationships between objects and content.

Having previous to my ADE experience spent little time around historical editions, I never quite got used to all the talk of “documents” at camp edit or in the ADE meeting that followed it. At the Blake Archive we usually only say “documents” to refer to the documentation we generate in the process of editing “works” and “objects”. This difference in speaking had me thinking about the questions I wanted to address in my own presentation to the ADE regarding how the manuscripts and letters projects in the Blake Archive have brought about some interesting changes in the way that editorial definitions based on the earlier illuminated books and visual designs have been applied and rationalized. I gleaned from the enthusiastic reception of an earlier presenter’s questioning of the durability of digital editions (she said she’d migrate to a digital edition when someone could show her how to read an electronic text without electricity, bringing to my mind the Olympic ads for NBC’s upcoming post-apocalyptic “Revolution”) that my intended discussion of some of the peculiarities of our XML tag set for manuscript transcriptions might not be the most compelling choice for the group assembled. In my presentation about the letters in our edition not in Blake’s hand, titled “Complicated Correspondence: Editing the Letters William Blake Did Not Write,” I expanded on some of the less overtly technical repercussions of earlier precedents set in the Blake Archive to the work we’re doing now on new types of objects and works. My argument was that the usages of “works”, “copies,” and “objects,” even when used as literally and diplomatically as they have been in the Blake Archive, become another layer of technology mediating users’ access to content. As much a technology as the codex or digital machines used to flip or navigate pages, these terms require continual re-inspection as they are applied to new ends.

Along these lines, I am excited to hear our editors are planning to push more of the documentation for the Archive onto the public site in the near future. Hopefully such a move will encourage us to keep our editorial machinery well oiled, in addition to providing a resource for other editorial projects.

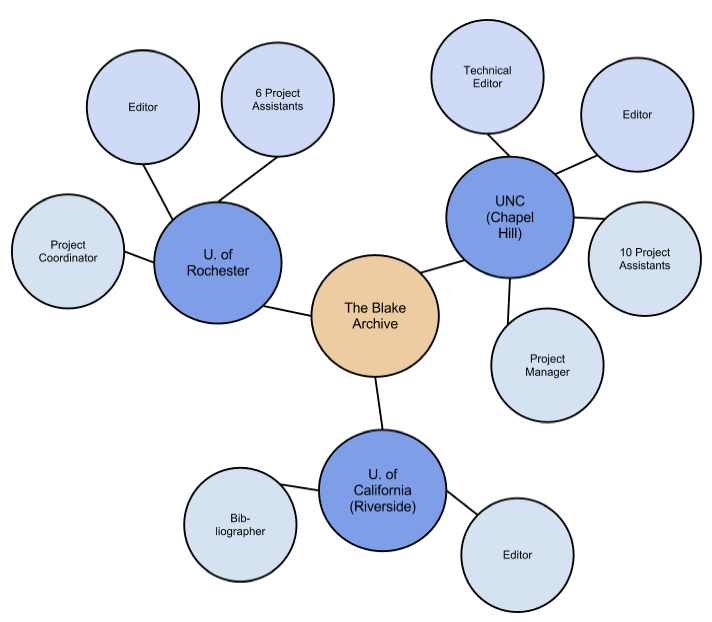

Continue readingThe Blake Archive has people all over the place. Three editors at three different institutions in three different states, two “teams” of project assistants/graduate students, a Technical Editor (grad student), Project Manager (grad student), and Project Coordinator (grad student—that’s me!).

The domain of Team Rochester (or more informally, BAND: Blake Archive Northern Division) is Blake’s manuscripts and (more recently) typographic editions. Our first publication was Island in the Moon and we’re currently working on electronic editions of Blake’s letters, the Genesis Manuscript, Poetical Sketches, and Four Zoas. Typically, teams of project assistants work together on a single text or group of texts (as in the case of the letters), but sometimes individuals work alone on “easy” manuscripts (which is really a misnomer for anything of Blake’s).

As the job title (Project Coordinator) implies, my job is to coordinate projects. This means several different things, but mainly I keep track of who’s working on what at the UR and I coordinate BAND’s activities with the Project Manager, Ashley, at UNC. The digital heart of the Blake Archive—its servers—is at UNC. Which means that the work we do at the UR involves complicated procedures to log in securely from far away. BAND is also the newest “wing” to the Blake Archive. Combine a bunch of people relatively new to the Blake Archive and the world of electronic textual editing with the labyrinthine world of servers, “tunnels,” and “run this command in the terminal window” [“What’s a terminal window??!”] and you can see the need for some coordination.

As the job title (Project Coordinator) implies, my job is to coordinate projects. This means several different things, but mainly I keep track of who’s working on what at the UR and I coordinate BAND’s activities with the Project Manager, Ashley, at UNC. The digital heart of the Blake Archive—its servers—is at UNC. Which means that the work we do at the UR involves complicated procedures to log in securely from far away. BAND is also the newest “wing” to the Blake Archive. Combine a bunch of people relatively new to the Blake Archive and the world of electronic textual editing with the labyrinthine world of servers, “tunnels,” and “run this command in the terminal window” [“What’s a terminal window??!”] and you can see the need for some coordination.

At the UR, I keep track of who is working on what and how they’re doing. This is primarily accomplished through our weekly staff meetings, for which I set agendas (and during which another project assistant takes minutes). These get posted to BAND’s Google Site, which we use to keep track of things like meeting minutes, technical documentation (for example, the XML tagset for transcribing manuscripts), project documentation (such as proofreading questions), and the links we use frequently. We had been using Blackboard for a while, but we recently migrated to a Google Site, and that seems to work really well for us.

One of the advantages of using a Google Site is that it plays well with Google Docs, which we use extensively. All of our project tracking and proofreading takes place in and through shared Google Docs. As team members begin transcribing and encoding Blake’s text into XML, questions tend to arise. At that point, someone will start a Google Doc for that project, record their questions, and then share it with the rest of BAND. Some of the easier questions (such as “Do we transcribe the handwriting of librarians or archivists?” (Answer: no)) will be answered via the comment feature, or in differently formatted text. Trickier questions (by far the more common species) we address during our weekly meetings, and occasionally escalate to the Blake Archive’s listserv, which gives non-UR folks (typically the other editors, the Project Manager, and/or the Technical Editor) a chance to weigh in.

Once a MS has been transcribed and encoded, it’s ready to be proofed. Once again, we record errors (such as typos) and questions (“Is that a comma or a period?”) in a Google Doc. BAND spends a lot of time scrutinizing small details and discussing at length whether or how to record/transcribe/encode something. In a few seconds and with just a few clicks, project assistants can neatly snip a close-up of whatever mark, letter, word, or line they have a question about and insert that into the proofreading document. Having images right next to specific interpretive questions makes our detailed discussions (which have been known to induce brain-death and existential confusion) about things like dashes much easier to manage. In fact, our reliance on these kinds of images contributed to one of the new features in the Archive, which debuted with Island in the Moon: text-note images in the editorial notes to help explain particularly knotty editorial cruxes. Here’s an example from Object 2 of Island in the Moon:

One last word about managing the work of proofreading. We just started using a Google Survey to make proofing more consistent. Nick Wasmoen, one of the project assistants at the UR, built a proofreading form in Googledocs, which we now use for all of our proofreading. It details everything a proofer needs to check, from typos in the title to errors in copy information or the transcription. Using the document maintains consistency in proofing across texts—this is especially important as we all proofread each other’s work, and this ensures that we all look at and for the same things.

Another aspect of my work at the Blake Archive is being the link between BAND and the folks at UNC—especially the Blake Archive Project Manager, Ashley. When BAND members run into problems I can’t solve (such as log-in issues on the server) or questions I can’t answer, I talk to Ashley. We have regular video chats, during which we share updates about project progress and I get to ask lots and lots of questions about how and why the Archive works the way it does. We’re using Google Video Chat, which seems to work well a majority of the time. We occasionally have issues where one of us can neither be seen nor heard, but it usually works.

Sometimes I’m conflicted about relying so much on Google for tracking and managing our collaborative editing projects. But it’s just so easy! And free! And right there! And easy! And when you spend hours scrutinizing ink splotches or determining whether that “s” is *really* capitalized, “easy” works.

Continue readingA research project of the Humanities Division of the University of Oxford, the Electronic Enlightenment invites you to “explore the original web of correspondence: read letters between the founders of the modern world and their friends and families, bankers and booksellers, patrons and publishers.” While EE clearly defines itself as a digital project, “a ‘living‘ interlinked collection of letters and correspondents” (FAQ), its foundation is made of paper; that is, the primary source of its content (at this point) have been the print editions of academic presses.

From “Principles of the Edition:”

To date, most of the content of EE has been provided by printed editions of correspondences from academic presses worldwide; nevertheless, it should not be viewed simply as an aggregation of these editions. Rather it is a database of individual letters and correspondents that can be searched or browsed as a complete collection.

From the “Introduction:”

EE has as its foundation major printed editions of correspondence centred on the “long 18th century”. From the correspondence itself, the supporting critical apparatus and additional research carried out by EE, we have developed a set of information categories, from dates and names to textual variants — indeed, any piece of information that contributes to our understanding of the documents. The data captured within these information categories enriches EE as a digital academic resource, by creating an intricate network of connections between the documents.

EE provides access to over 53,000 letters and documents from several centuries (the earliest letter is from 1619), correspondent bi0graphies, and explanatory notes (depending on the source edition, these might be editorial, textual, linguistic, or general notes). The searching capabilities appear extensive; users can search for letters by content (words or phrases), author name, place of origin, date (including day, month, and year), recipient, and the city or country where it was received.

Moving beyond its bookish roots, EE openly invites user collaboration. Users can supply missing information about biographies, dating of documents, locating correspondents, and translations. Readers can submit new letters for electronic publication. Scholars can even develop their own born-digital projects. From “Contributor Services:”

EE will provide a creative space for scholars to develop new born-digital critical editions of correspondences online. It will offer a central area where progress reports can be posted or linked, discussion lists for collaborators and testers maintained, and project results published. When prepared, these editions can be integrated seamlessly into the full collection of EE.

EE offers born-digital editions the possibility of publishing correspondence collections online, integrated into our network of biographical and documentary links.

Despite all of this exciting, collaborative coolness, however, access to the project seems to be by institutional subscription only. (Even the “free trial” available through Oxford University Press seems to be tied to institutional affiliation.)

Continue readingLisa Spiro at Digital Scholarship in the Humanities started her review of the digital humanities in 2008. She starts with the “Emergence of the Digital Humanities,” and considers NEH’s establishment of the Office of the Digital Humanities as “giving credibility to an emerging field (discipline? methodology?).” The next section is (fittingly) “Defining ‘Digital Humanities,'” where Spiro traces critical key definitions of the “Digital Humanities,” such as discussions of whether it is a method, field, or medium. The last section of this first part of her review is “Community and Collaboration,” which surveys virtual networks of scholars, Humanities Research Centers, and Twitter as “a vehicle for scholarly conversation.”

Continue readingVia A Repository for Bottled Monsters (“An unofficial blog for the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, DC.”): The Washington Post has a story up about the Smithsonian’s efforts to join the digital age, starting with “Smithsonian 2.0,” a gathering of Smithsonian curators, staff, and such digital luminaries as Clay Shirky (we wrote about an interview with him here), Bran Ferren (co-chairman and chief creative officer of Applied Minds Inc.), George Oates (one of the founders of Flickr), and Chris Anderson (editor in chief of Wired). [Update: Dan Cohen was also there, and wrote about his responses here.]

Probably the most provocative point raised in the article is the role of the curator, or expert, in the Smithsonian’s digital future. Institutions like museums (or presses) have traditionally occupied the role of gatekeepers (to steal a term from mass communication), choosing “the best” from the masses to display (or sell). For example, less than 1% of the museum’s 137 million items are on display. As many have pointed out, digital technologies change how information is generated and shared, and within the context of 2.0 technologies, crowd-sourcing, and remixing, the role of the expert and conceptions of authority are also transforming – transformations actively “promoted” in the digital humanities imagined in the forward-thinking “Manifesto” from UCLA’s Mellon Seminar in Digital Humanities:

Digital humanities promote a flattening of the relationship between masters and disciples. A dedefinition of the roles of professor and student, expert and non-expert. (paragraph #20)

For those involved in historically curatorial institutions like museums, archives, and the ivory towers of higher education, an identity crisis looms. Anderson’s message to the Smithsonian is that gatekeepers “get it wrong,” the influence of curators will never be the same, and that in fact, the “best curators” have not yet emerged from the crowd.

“The Web is messy, and in that messiness comes something new and interesting and really rich,” he said. “The strikethrough is the canonical symbol of the Web. It says, ‘We blew it, but we are leaving that mistake out there. We’re not perfect, but we get better over time.’ ”

The problem is, “the best curators of any given artifact do not work here, and you do not know them,” Anderson told the Smithsonian thought leaders. “Not only that, but you can’t find them. They can find you, but you can’t find them. The only way to find them is to put stuff out there and let them reveal themselves as being an expert.”

Compare this optimism, emphasis on shared knowledge, and confidence in the hidden expertise of the public with a new project called brainify.com, a social-bookmarking site only for academics, or more precisely, those with university email addresses (which already excludes a great number of academics in the position of adjuncts, who often don’t get university email accounts). The Chronicle of Higher Education just ran an article about the site’s debut (“‘Social Bookmarking” Site for Higher Education Makes Debut”), and cites creator Murray Goldberg’s rather different take on the value of public contributions:

Mr. Goldberg said that he wanted to focus on solidifying the site’s functions for students and faculty members before exploring the possibility of expanding membership. “As soon as we open up membership for bookmarking to a broader audience, we risk dilution of the quality of the site.”

Hm, so Anderson sees expertise revealing itself from within the public, while Goldberg fears a dilution of “quality.”

In general, I agree with Goldberg’s assertion that “the world needs an academic-bookmarking tool.” Filters are important; they allow users to manage and control the overwhelming amount of information available on the web. Clay Shirky asserts that the charge of “information overload” is actually a problem of inadequate filtering. And as a graduate student and instructor, I can understand that academic needs and interests might vary from that of the general public, necessitating different sets of tools. But ultimately, I question whether the deliberate construction of a “walled garden” (as Melanie McBride calls it) is the best way to meet the varied needs of academics. That is, using exclusivity to order and manage the “messiness” of the web – trying to avoid the strikethrough – is not truly engaging the huge potential for networked knowledge.

I’ll leave Anderson with the final word:

Continue reading“Is it our job to be smart and be the best? Or is it our job to share knowledge?”

The Mellon seminar in Digital Humanities at UCLA has published “A Digital Humanities Manifesto” which allows users to comment on individual paragraphs or the entire document. Between the initial post and the 70ish comments on the page emerges an interesting discussion about what – exactly – characterizes the digital humanities, the role of print media in the practices and projects of the digital humanities, the shifting relationships between experts and amatuers, and the impact of all of this on the boundaries of institutions and disciplines.

Continue reading