This past weekend, I attended the Buffalo Small Press Book Fair, held annually at the Karpeles Manuscript Library Museum. As in years past, some of my favorite booths are the letterpress vendors, but there are lots of great handmade books, zines, comics, screenprinted posters, and small press books of local history, poetry, and prose. This year, there were also workshops on book binding, screen printing, and zines. Rochester artist, illustrator, and designer Peter Lazarski ran the zine workshop, which included a brief history of zines and an easy tutorial on crafting a small, 8-page booklet. Peter also passed around a copy of Watcha Mean, What’s a Zine? (by Esther Watson and Mark Todd) and I was surprised to see Blake mentioned in “Great Moments in Zine History.”

But of course, it makes perfect sense. Through illuminated printing, a process of relief etching, Blake believed he had solved two major problems in c18 print culture: the separation of text and image, and the difficulty of self-publication. I’ve posted his 1793 prospectus to the public elsewhere, but I’ll repost here. Advertising his new process, Blake writes (emphasis mine):

The Labours of the Artist, the Poet, the Musician, have been proverbially attended by poverty and obscurity; this was never the fault of the Public, but was owing to a neglect of means to propagate such works as have wholly absorbed the Man of Genius. Even Milton and Shakespeare could not publish their own works.

This difficulty has been obviated but the Author of the following productions now presented to the Public; who has invented a method of Printing both Letter-press and Engraving in a style more ornamental, uniform, and grand, than any before discovered, while it produces works at less than one fourth of the expense.

If a method of printing which combines the Painter and the Poet is a phenomenon worthy of public attention, provided that it exceeds in elegance all former methods, the Author is sure of his reward.

Self-publishing multi-media work is clearly in line with current DIY crafting aesthetics; MAKE magazine has both a tutorial on illuminated printing and an article on Blake’s self-publishing (thanks to Laura for the link!).

It was certainly possible to print images and text together in c18, but it was difficult to do so. As Joseph Viscomi explains in his essay “Illuminated Printing:”

Technically, such integration was possible in conventional (intaglio) etching… but the economics of publishing had long defined etching as image reproduction and letterpress as text reproduction, so that the conventional illustrated book was the product of much divided labor, with illustrations produced and printed in one medium and shop and separately inserted into leaves printed elsewhere in letterpress on a different kind of press. Even when words and images were brought together on the same leaf, divisions in production were maintained.

Conventional intaglio printmaking involves incising designs into the surface of a copper plate; etching uses acid, and engraving uses sharp, hard tools. (For a great video of intaglio printmaking, check out this video from the Minnesota Institute of Art.) Throughout the c18, many illustrations were engraved reproductions of original works of art, including statuary, paintings, water colors, sketches, and drawings. Engravers developed many techniques to emulate the look of original works; with their tools and techniques, they could imitate wash drawings, chalk lines, light washes of color, and the texture of pencil. (For more about imaging technologies in the c18, see William Ivins’ Print and Visual Communication.) They also developed techniques of line systems, such as cross hatching and dot-and-lozenge, which allow them to imitate a range of tones and lines. You can see below a detail of one of Blake’s commercial engravings showing dot-and-lozenge (from Viscomi’s “Illuminated Printing“).

Detail “Orlando Uprooting a Pine,” engraved by William Blake after Thomas Stothard

Unlike the straight lines of engraving — or the “neat, tidy, characterless and fashionable net of rationality” (as Ivins calls it) — Blake’s process allows a more fluid line, integrated text and image, and ultimately more creative control over the entire process. Instead of cutting straight lines into copper, Blake can draw, write, and paint with pens and brushes.

In practice, Blake wrote texts and drew illustrations with pens and brushes on copper plates in acid-resistant ink and, with nitric acid, etched away the unprotected metal to bring the composite design into printable relief. (Viscomi, “Illuminated Printing“)

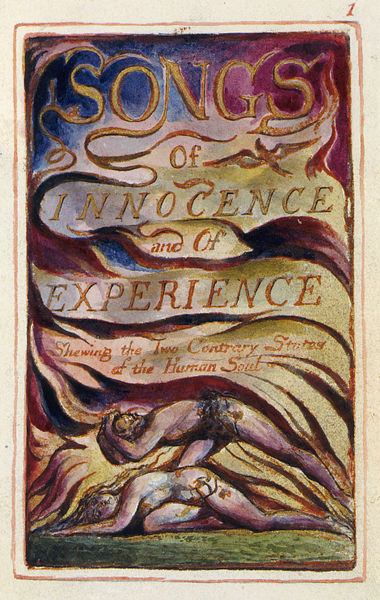

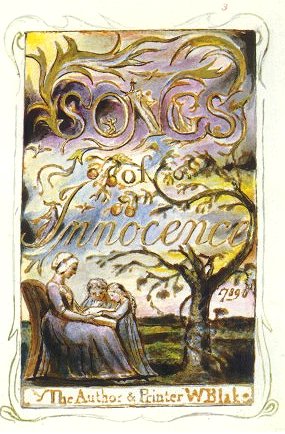

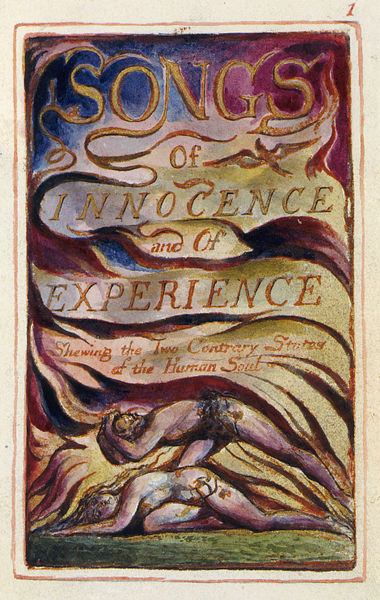

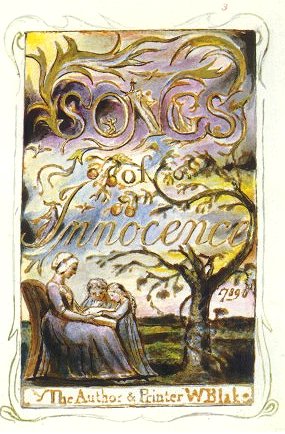

Illuminated printing united the work of the poet and the artist by giving him more direct control over the whole process. And despite the fact that Blake could make multiple prints of each plate (thereby creating “exactly repeatable” verbal and visual statements — one of the defining characteristics of print culture), the illuminated books look handcrafted: Blake and his wife Catherine hand-colored many of the images after printing, there is a lot of variation in the color palettes between individual copies of a book, and the poetry — written backwards by Blake onto the plate — resembles handwriting, not standardized typography.

Image from Wikimedia Commons

Image from Wikimedia Commons

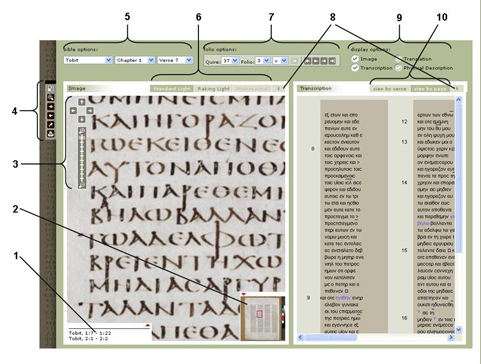

If you want to see more, go to the Blake Archive, and select any illuminated book. If the Blake Archive has published more than one copy of a work, be sure to hit the “Compare” button beneath the image, and you can see how that page looks in each copy.

Continue reading