Recently, while looking for inspiration for a poetry assignment, I revisited one of my favorite poems, Allen Ginsberg’s “Sunflower Sutra.” I always loved this poem for its energy and relentless optimism. After arriving at a dock and sitting “under the huge shade of a Southern/Pacific locomotive to look at the sunset over the/box house hills and cry,” Ginsberg sees a dead sunflower and goes into a fit of emotions, ending with the cheery declaration, “we’re all beautiful golden sunflowers inside.” But this journey is not easy. Before Ginsberg’s uplifting conclusion, we’re first taken through a sort of microcosm of the industrial wasteland that is America:

all that dress of dust, that veil of darkened railroad

skin, that smog of cheek, that eyelid of black

mis’ry, that sooty hand or phallus or protuber-

ance of artificial worse-than-dirt—industrial—

modern—all that civilization spotting your

crazy golden crown—

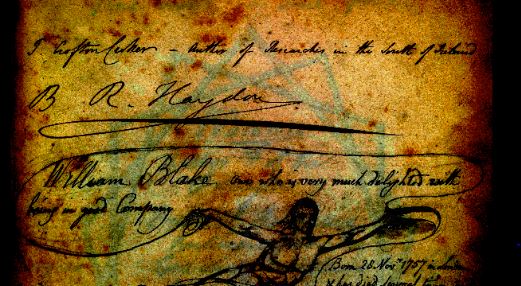

Ginsberg paints a rather bleak picture and most fascinatingly, all this dust and soot is triggered not just by the sunflower, but my Ginsberg’s “memories of Blake—my visions—Harlem.” I never understood what this line meant and never bothered to look into it. But being as I have recently started to work with the Blake Archive, I figured this would be a good chance to learn a bit more about William Blake and his work.

Ginsberg is referencing two things with this line. The first is his literal vision, though it would be better described as an auditory hallucination. Ginsberg claims to have heard the voice of William Blake reading his poetry and has said in interviews that this experience was very profound for him. Interestingly enough, Blake also claimed to have had visions as well and used these to inform his art and writing. Second, and more specifically, Ginsberg is referencing Blake’s poem, “Ah! Sunflower.”

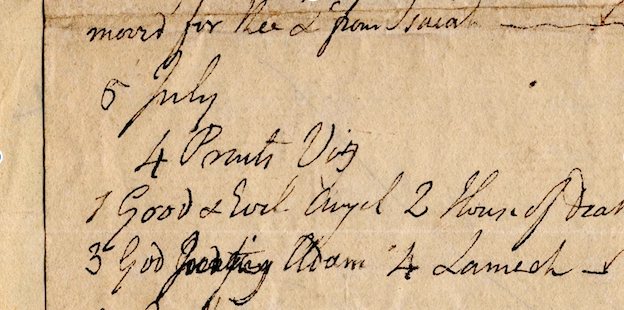

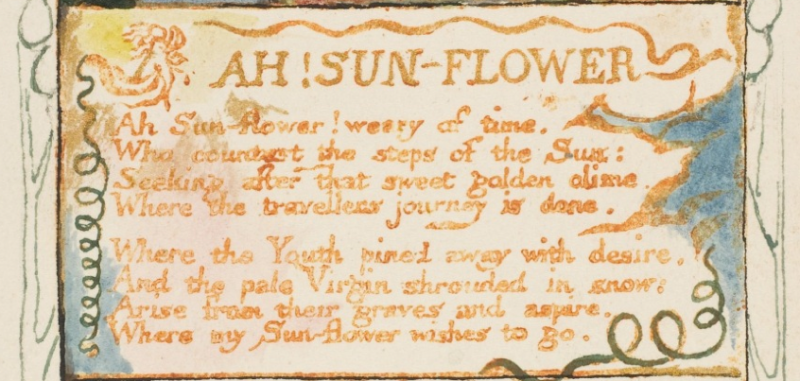

“Ah! Sunflower” is a short poem from Blake’s collection, Songs of Experience, printed in 1794. The poem is so short it makes sense to just quote it in its entirety here:

Ah Sunflower! weary of time

Who countest the steps of the Sun:

Seeking after that sweet golden clime

Where the traveller’s journey is done.

Where the Youth pined away with desire,

And the pale Virgin shrouded in snow:

Arise from their graves and aspire,

Where my Sun-flower wishes to go.

The Penguin edition of Blake’s Selected Works, edited by Christopher Ricks, has this to say about the phrase, “my Sun-flower”: “When Apollo deserted Clytia, ‘she pined away and was changed into … a sun-flower, which still turns its head towards the sun in his course, as a pledge of love.'” An article by George Mills Harper titled, “The Source of Blake’s ‘Ah! Sun-flower'” has different ideas about the meaning of this poem, claiming that Blake was inspired by Thomas Taylor’s translation of the Hymns of Orpheus. Harper’s analysis focuses on the sunflower’s climb from the material world up towards the sun or heavens of the spiritual world: “The sunflower, the youth, and the virgin—’natural things’ all and bound in their ‘graves’ of temporal existence—aspire to the sun’s eternality.” Later Harper states:

But we must remember that the flower has a ‘terrene quality.’ It is rooted in the earth, and the very roots themselves are symbolic to both Taylor and Blake of the material life. ‘But in the celestial regions,’ Proclus explains, ‘all plants, and stones, and animals, possessing [sic] an intellectual life according to a celestial nature.’ These ‘celestial regions’ represent the ‘sweet golden clime’ to which Blake’s sunflower, youth, and virgin ‘aspire’ to go.

Likewise, we see a similar ascent in Ginsberg’s poem (not spiritually but thematically), rising from the “Hells of Eastern rivers” and “growing into mad black formal sunflowers in the sunset.” While both poems are ultimately positive in their messages, both contain moments of darkness by which to contrast this ascent. In “Ah! Sun-flower,” we have the flower being described as “weary of time.” The youth is described as “pin[ning] away with desire.” And the virgin is pale and “shrouded in snow.” But in the last two lines, they “arise from their graves” and follow the sunflower into the heavens.

In “Sunflower Sutra,” we see a similar contrast; lots of dust, soot, rust, and smoke is eventually cleared away by golden beauty. The difference though is where this transformation takes place. While the sunflower, youth, and virgin arise towards the sky, the heavens, and make their “sweet golden clime” in Blake’s poem, Ginsberg informs us that this journey should be directed inward rather than outward:

–We’re not our skin of grime, we’re not our dread

bleak dusty imageless locomotive, we’re all

beautiful golden sunflowers inside, we’re bles-

sed by our own seed & golden hair naked ac-

complishment-bodies

For Ginsberg, the “sweet golden clime” of Blake does not suffice. Instead, we must turn inwards and seek truth and beauty there, rather than outside of ourselves. This makes sense considering Ginsberg’s belief in Buddhism, which focuses on introspection and turning inward as opposed to Christianity, which directs one’s thoughts and spirituality outward to God.

Both poems are beautiful and deliver optimistic messages in their own unique ways. Perhaps Ginsberg only mentions Blake as a jumping off point to shift the scene from San Francisco back to his memories of Harlem (where he had his vision of Blake). But I think it’s worthwhile to ponder whether or not Ginsberg references Blake so that we might consider the difference between a spirituality that directs us outwards, towards the heavens, and a spirituality that directs us inwards, towards ourselves.