Recently I saw a message from university advancement that mentioned a “gift burst,” whereupon I resolved to label our next publication announcement an issue burst. I’m imagining celebratory confetti fluttering down as we release our winter issue (vol. 54, no. 3) online today. As ever, it will be open access until the end of the month.

In this issue:

- Alexander S. Gourlay remembers John E. (Jack) Grant

- Kang-Po Chen reexamines autoeroticism in Visions

- Katharina Hagen analyzes the Bruce Dickinson song “Gates of Urizen”

- Shelley King and John B. Pierce detail the interesting history of a copy of Job

Kath’s article involved a first for me: securing a permission to reproduce lyrics. Unlike my experiences with images, where there’s usually an easily identifiable institution involved, this permission was a tough nut to crack—just discovering the identity of the music publisher that manages the copyright was a challenge. It took us from January to November from putting out the first feelers to acquiring the permission document (of course it’s hard to say how much the circumstances last year extended the process).

Kath has written up her thoughts:

Lyrics can be exempted from the fair use regulation which allows the use of copyright-protected texts for research purposes. Having print permission for lyrics can thus be obligatory. Our quest to obtain this permission was a long and adventurous one. Giving up was not an option; I did not want to publish my article without the respective lyrics and a wise man once said “He who desires but acts not, breeds pestilence.” The difficulty lies in finding the right contacts and getting the attention of the music industry. I have not tried this myself, but I strongly suspect that it might be easier to find the Holy Grail. At some point it was decided to seek advice within the fandom of the band Iron Maiden, for whom Bruce Dickinson currently functions as frontman and singer, and most answers amounted to that this was an impossible thing to do. Or, more bluntly: “Give up.” “They will never answer you” (totally ignoring the fact that finding out who “they” may be is the biggest hurdle). Yet, I am deeply indebted to the one person from the Maiden fan community who gave me the right hint on how to embark on our quest. Once we had the right starting point, our golden thread that would lead us to Jerusalem and its gates, I began to feel slightly optimistic to do the undoable. This optimism was well justified, as in contrast to the gloomy predictions, I did receive an answer to my inquiry. We had more obstacles to overcome, but by rolling up the golden ball we finally passed the gates.

I want to express in this place my thankfulness to all parties involved, especially Sarah Jones for her patience and effort during our ostensibly endless pursuit to gain this permission which even required postponing the publication of my article. In the end, we finally did the undoable and “what is now proved was once, only imagin’d.”

Many thanks to her for the summary and the (utterly unsolicited!) acknowledgment.

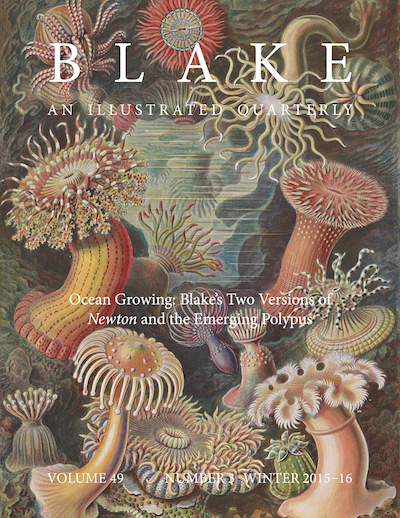

Our latest open access issue is vol. 49, no. 3 (winter 2015–16). Its main article is Joe Fletcher’s discussion of the two extant impressions of Blake’s color print Newton. We didn’t put Newton on the cover and instead came up with an image of anemones from the Library of Congress. Ironically, I got more positive comments about that cover than I’ve ever had for a Blake one! The issue also includes Sibylle Erle’s review of Colin Trodd, Visions of Blake: William Blake in the Art World 1830–1930, and three notes: Jenijoy La Belle and Robert N. Essick on a vignette in the Dante illustration Dante in the Empyrean, Drinking at the River of Light ; Angus Whitehead on an early reference to Blake and the ghost of a flea; and Jerry Bentley on newly discovered material about W. S. Blake. Of all the William Blakes in London who were not the William Blake, William Stadden Blake is important because he was also an engraver, so the potential for confusion is greater.