This guest post is by Natasha Bharucha, a recent graduate who contacted us to ask if she could participate in our Blake projects. It has been lightly edited for style.

The trope of scattering literature, in particular poetry, with images of red roses—like a kitsch welcome to a honeymoon suite—is hardly a novelty. The metaphorical purpose of the rose is usually to signal the desirability of a woman. In a way, William Blake is using the same figurative image to do so in his poem “The Sick Rose.” But in many ways he is not.

I first encountered the magical work of Blake in school and, to be quite honest, I did not really like his poetry very much. We were reading Songs of Innocence and of Experience and I initially found them agitating, inconclusive, and old fashioned. However, the more time I spent with them and the more I read them in their intended illustrated form, the more I felt drawn to Blake’s artistic project. This fascination ultimately led to his being the sole focus of my undergraduate dissertation, where I researched the ways he anatomizes the human eye in his later works Milton and Jerusalem (as well as The Four Zoas) and how this detailed and specific engagement with the eye reflects his broader attitudes to the act of seeing. I hope to research this theory of vision in more depth as I progress in my studies. I am mentioning this because how Blake challenges our understanding of perception is directly relevant to my current musings on “The Sick Rose,” a poem that perplexes:

What strikes me most is Blake’s use of figurative language and how his choice of words directs our attention to the slipperiness of distinguishing between the literal and the figurative. Perhaps it is this very slipperiness that gives the poem its status as what Nathan Cervo calls “one of the most baffling and enigmatic in the English language.” In order to understand how Blake’s language is working, we must briefly consider the difference between conceptual metaphors and novel metaphors. Conceptual metaphors refer to metaphors that govern our thought processes, basic metaphorical mappings that do not strike us as notably figurative, such as saying that something is the “source” of our passion. Novel metaphors refer to unconventional metaphors that are the result of poetic creations. In “The Sick Rose,” Blake makes use of both in ways that blur the boundary between the literal and the figurative and encourage us to rethink not only what idealized love is but how that very idealization is problematic.

Blake uses images of the rose and the worm, depicting how the invertebrate desires to “destroy” the flower. The simple presentation of this image accompanied by the verb “destroy” invokes the common metaphorical conception of feelings being stated in terms of consumption and food. The Oxford English Dictionary defines this verb with synonyms such as “consume” and “demolish,” words associated with eating. These connotations strengthen the image of the worm eating away at the rose in a process of destruction. A customary metaphorical reading of this poem is to view the subject of the apostrophe, the rose, as a woman, and the worm as a phallus. The scene is ripe with imagery of lust (e.g., “crimson joy”). This is not a difficult metaphorical leap for us to make cognitively. George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, whose work on conceptual metaphor is significant, would perhaps argue that the cognitive framework of “ideas as food” is at work here. A case can be made for this overarching framework when we examine the dictionary definition of “lust,” a central theme in Blake’s poem: “Desire, appetite, relish or inclination for something” and “sexual appetite or desire.” The repetition of the word “appetite” illustrates the ways in which the “ideas as food” framework can be integral to our understanding of abstract concepts. It is a familiar conceptual metaphor, rendering the jump from “destroy” to devour and physical “appetite” to lust undetected. This constitutes a “weak metaphor,” as it requires little interpretative effort to comprehend. Our culturally informed system allows us easily to associate lust with the image of the worm destroying the rose. Similarly, the overarching conceptual metaphor that Lakoff and Johnson identify as “plants as people” can be detected. The rose is immediately personified and thus used figuratively, as indicated by the use of the personal pronouns “thou” and “thy,” which reinforce the reading of the rose as a woman being lusted after.

However, although “The Sick Rose” follows familiar conceptual metaphors, its expression is unconventional. Cognitive metaphorical structures are indeed detectable in the poem, but poetic and rhetorical experimentation of metaphor can complicate our comprehension. The database Literature Online (LION) shows that there are 332 instances in poetry from 1000–2020 where the personal pronoun “she” is used within close proximity of “red rose.” In stark contrast, there are merely sixteen occurrences of “sick” near “rose”; they do not collocate with one another. The conventionality of referring to a woman/object of desire as a rose is distorted when coupled with illness. As a result, conventional cognitive leaps are stunted and instead we are left wondering why Blake has transformed the image. For me, he is not only writing a poem about the inevitability of destruction; he is also drawing attention to the flimsiness of idealized images and the problems they create. Michael Srigley argues that the “invisible worm” is not phallic, but rather the absence of fulfilled sexual union and the ensuing fantasized urges of the sexually repressed:

The poem is therefore an expression in a powerfully compressed and suggestive form of Blake’s conviction that the Church’s condemnation of sexuality as intrinsically shameful has caused a widespread social and psychological sickness. It leads to the breaking of the marriage bond, to prostitution, to venereal disease, and to a fevered eroticism that is essentially unhealthy. (8)

I find this reading compelling, because it deals with the notion that a source of destruction is the maintenance of ideals. Blake deconstructs this notion, not only thematically but also linguistically, by creating a novel metaphor that undermines the ideal of a beautiful rose.

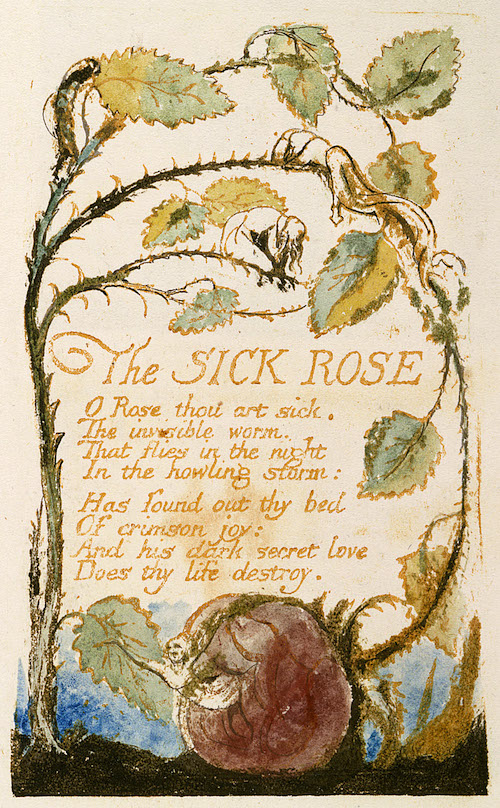

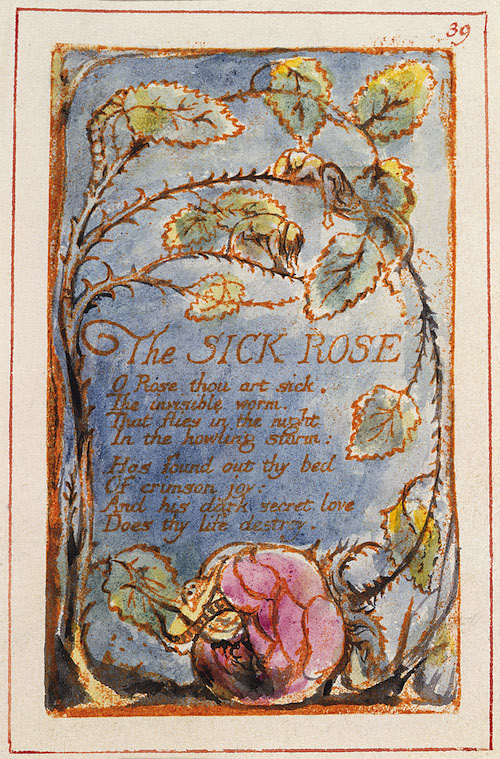

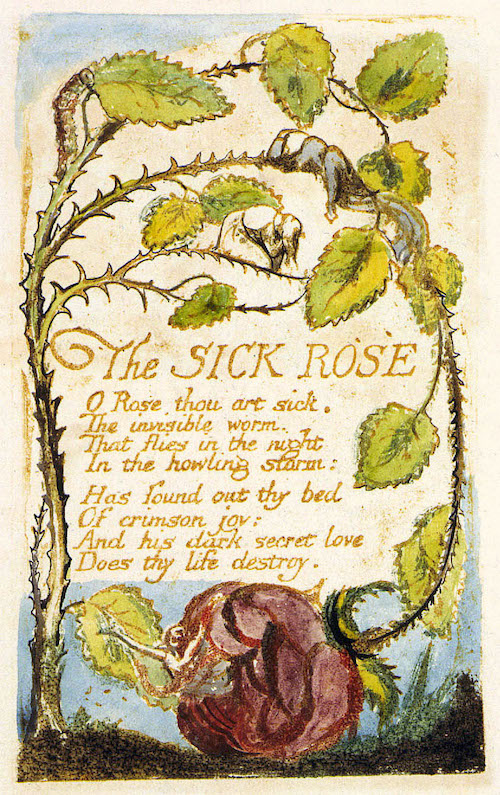

The polysemy of the rose’s sickness is striking, mingling physical and mental illness. This multiplicity is not obscuring but illuminating. In fact, the figurative use of language here pierces at a reality assembled from plurality. The use of the word “bed” in the text continues this exploration of multiplicity of meaning. The literal meaning in this context is that of a flowerbed, but the extended metaphor of the rose as a woman implies the “bed” is her place of rest and procreation, as well as the possibility of it being read as a deathbed. To be able to establish such linkage and recognize the connection between various images and implications is perhaps the real meaning of the poem. Sadock states: ”When the literal sense of an uttered … word is in apparent conflict with the cooperative principle … the hearer is forced to seek a figurative … intent” (43). Analysis of “The Sick Rose” disproves this, for both the literal and figurative can be held simultaneously in a way that is not “lacking in justification” (43). It is precisely the coexistence of the literal and figurative within the same context that renders linguistic figures noteworthy and distinct from cognitive metaphors. This symbiosis between literal and figurative meaning weakens a distinction between the two. Not only is the figurative also literal, the literal is figurative. Blake actively works on this assumption in his illustration. He depicts the curved stem of the rose with women curled up on the bough; the dense head of an almost blooming rose has a women’s torso bending out of it. The Blake Archive description states that the “two gowned females … represent roses that are dying blossoms or blighted buds.” This accords with Blake’s metaphor, but the females don’t just “represent” blighted buds in the illustration, they are blighted buds. Similarly, by fusing the rosebud with a female corpse, both the literal and figurative coexist visually. It is interesting to note that in some versions there is a worm half embedded in the rose too, and in some it remains absent, perhaps taking its status as “invisible” quite literally. For example, in copy B, pictured above, only the female is embedded in the rose, whereas in copies R and T the worm is given not only form but also a strong, black outline.

This suggests Blake was unsure whether to depict the worm as a worm—in which case its “invisibility” is lost, but a viewer can see the literal image of a rose “destroy[ed]” by a worm—or to show the worm as “invisible” but then notably not a worm, because we cannot see it, in which case the figurative ideas of what the worm could be, particularly as the absence of sexual satisfaction, are brought to the fore. Unlike with the rose, the invisible worm’s dual status as literal and figurative is difficult to depict visually. Nonetheless, perhaps copy C shows an attempt. In this print there appears to be a winding form of earthy color, but unlike in copies R and T, Blake avoids using a dark outline, and avoids marking the worm’s segments. Maybe he is trying to hint at the worm’s presence and absence simultaneously.

Blake’s lack of consistency illustrates his active engagement with literal and figurative language, and his plates as whole entities allow both types to coexist.

For me, “The Sick Rose” reveals the complex interrelatedness of conventional figure and subversion thereof, as well as the defining polysemy of literary figure. Blake’s extension of the conventional “people as plants” metaphor complicates the poem and jolts readers into a new mode of vision when conceiving of lust and its effects. One of the ways in which he prevents the reduction of his poem into the idealized form of singular meaning is by blending the literal and figurative, so that the poem drips with plural meaning, legitimizing both the very physical imagery and the abstract ideas that accompany it. I find this to be a breathtaking achievement in a mere eight lines.

Bibliography

Cervo, Nathan. “Blake’s ‘The Sick Rose.’” Explicator 48.4 (July 1990): 253-54.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980.

Sadock, Jerrold. “Figurative Speech and Linguistics.” Metaphor and Thought. Ed. Andrew Ortony. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. 42-57.

Semino, Elena. Metaphor in Discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Srigley, Michael. “The Sickness of Blake’s Rose.” Blake 26.1 (summer 1992): 4-8.