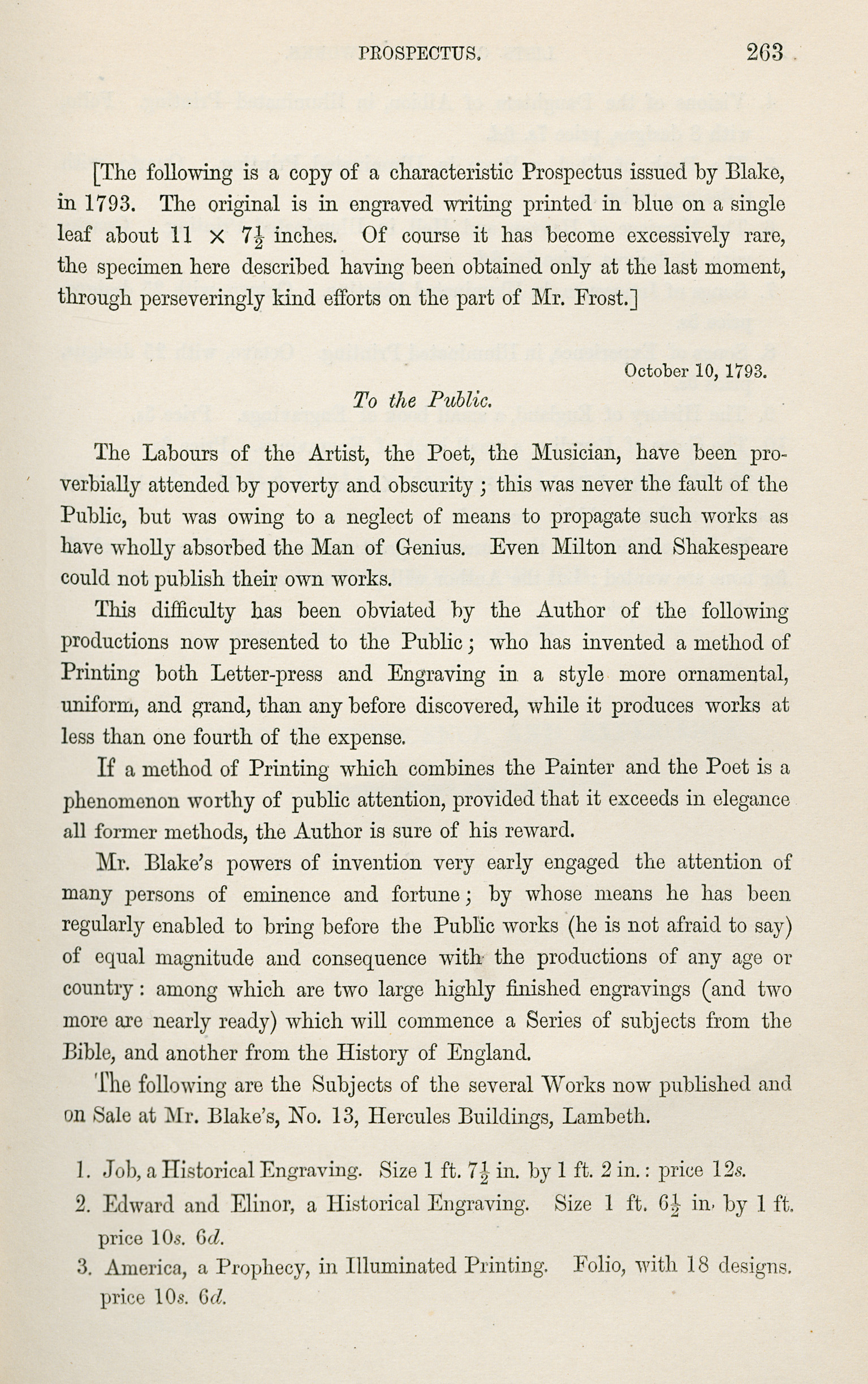

The William Blake Archive is pleased to announce the publication of a digital edition of To the Public, dated “October 10, 1793.” It first came to light in Gilchrist’s Life of Blake, 1863, where it was introduced with a brief heading that described “a characteristic Prospectus issued by Blake.” It had been transcribed from an “original…in engraved writing printed in blue on a single leaf about 11 x 7 ½ inches…obtained only at the last moment” from a “Mr. Frost”-perhaps William Edward Frost, a painter, member of the Royal Academy, and sometime collector of engravings by Blake’s friend Thomas Stothard (Bentley, Blake Books Supplement, page 142). Like several of Blake’s letters, then, his 1793 prospectus is known only from the transcription of unknowable accuracy from Gilchrist’s biography.

Blake was 35 when he published his prospectus. He and his wife were living in Lambeth, a suburb on the south side of the Thames, in a combination of living quarters, workshop, and retail shop. In one respect the prospectus is just a one-page advertisement for a youngish engraver trying to draw attention to his wares, with an opening pitch followed by a list of works and prices, phrased in the conventionally boastful, class-conscious advertising diction of its day: “Mr. Blake’s powers of invention very early engaged the attention of many persons of eminence and fortune; by whose means he has been regularly enabled to bring before the Public works (he is not afraid to say) of equal magnitude and consequence with the productions of any age or country.”

In other ways the prospectus punches, as they say, far above its weight. Its opening paragraph makes the startling claim that this engraver has solved the age-old problem of “the Artist, the Poet, the Musician, [who] have been proverbially attended by poverty and obscurity.” He pinpoints their fundamental dilemma, the inability to reach “the Public” across commercial barriers. Middlemen—publishers, printers, shop owners in control of the means of production and distribution—have been able to block the free expression of artists “owing to a neglect of means to propagate such works as have wholly absorbed the Man of Genius.” This 35-year-old engraver is not thinking of himself as a mere copyist but as an artist who belonged in the company of Britain’s greatest painters and poets: “Even Milton and Shakespeare could not publish their own works.”

In his opening paragraph Blake implicitly bills himself as an amalgam of Prince and Elon Musk, a great artist who has discovered a technology that can set others free. He is an entrepreneur offering a method with the potential to liberate the artist and the audience, previously thwarted through no fault of their own (“never the fault of the Public”), to commune freely and openly for the first time. This is to be accomplished by a revolutionary “method of Printing both Letter-press”—that is, texts—and “Engraving”—that is, pictures—”in a style” both grander and cheaper than heretofore possible. Blake implicitly claims that his invention would allow writers and artists to create and publish their works even if they were not trained engravers or letterpress printers. And, for several of his own works, Blake uses the language that has seemed to his posterity best fitted to label the products of his new technology: “Illuminated Books” in “Illuminated Printing”—phrases he never uses again.

Like so many visionary startups that promise to disrupt the status quo and replace it with liberating new technology, Blake’s was a failure. It did not spread to the artistic community as he imagines it might, by introducing learnable handmade elements in a composite medium capable of delivering, in any combination, anything that could be written or drawn and thus displace a prevailing system that had led the audience to expect, as the norm, mechanical regularity in specialized media.

Even his own use of his autographic medium probably played a large part in severely limiting his audience during his lifetime. Only decades later did mid-Victorian sponsors identify the problem and begin to separate Blake’s words from his pictures and foster the production of conventional editions of poetry that could be printed, published, and sold alongside Milton, Shakespeare, Tennyson, and Browning. With that radical move, “the Public” that Blake never blamed for his failures began slowly to convene and expand into the worldwide audience that we take for granted today. In a late reversal of fortune, that appreciative audience has found in the original composite form of “Illuminated Printing” Blake’s most tantalizing body of artistic work.

As always, the William Blake Archive is a free site, imposing no access restrictions and charging no subscription fees. The site is made possible by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with the University of Rochester, the continuing support of the Library of Congress, and the cooperation of the international array of libraries and museums that have generously given us permission to reproduce works from their collections in the Archive.

Morris Eaves, Robert N. Essick, and Joseph Viscomi, editors

Joseph Fletcher, managing editor

Michael Fox, assistant editor

The William Blake Archive