At the beginning of summer, my mom, who’s a sixth-grade English teacher, asked me to take her classes for a day. Working with young kids is a little out of the ordinary for a grad student, but it seemed like a good way to get my feet wet with teaching composition on the horizon. Plus, getting a glimpse of the potential obstacles, needs, and interests of an eleven-year-old learner was bound to offer me a valuable perspective that I may not otherwise get.

Of course, when you’ve been entrenched in texts like Wordsworth’s Preface to Lyrical Ballads, Henry James’ “The Figure in the Carpet,” or even George Eliot’s intricate Middlemarch for weeks, stepping into the shoes of a middle schooler is harder than you’d think. But, considering his association with children’s literature, Blake became an intuitive choice and Songs of Innocence didn’t disappoint. For the lesson, I went with “The Ecchoing Green” because of its straightforward narrative and clear figures of speech. The kids had only recently been introduced to basics like metaphors and similes, so the poem would be just right for an exploratory discussion. I did have some trepidation that 18th-century poetry would be too historically distant to capture their attention. But I should know better than to underestimate Blake.

Waiting for the first bell to ring, I was a little fidgety as my mom told me what to expect of her three classes. Two of them were supposed to be participatory and generally well-behaved. It was her last class that had a mischievous reputation. Thankfully, all I had to do was teach; my mom–who runs a tight ship–would be in the background for any major classroom management issues.

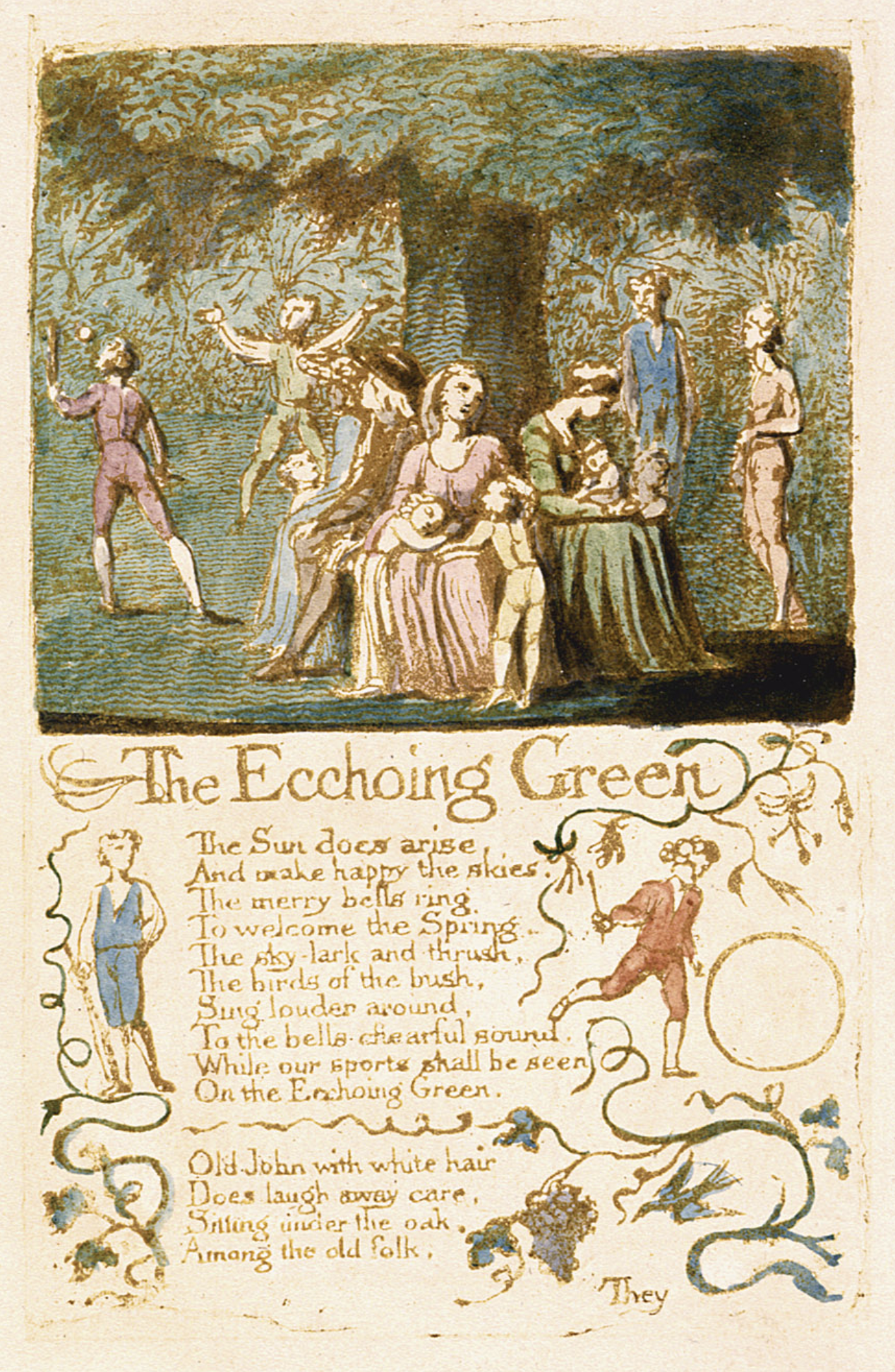

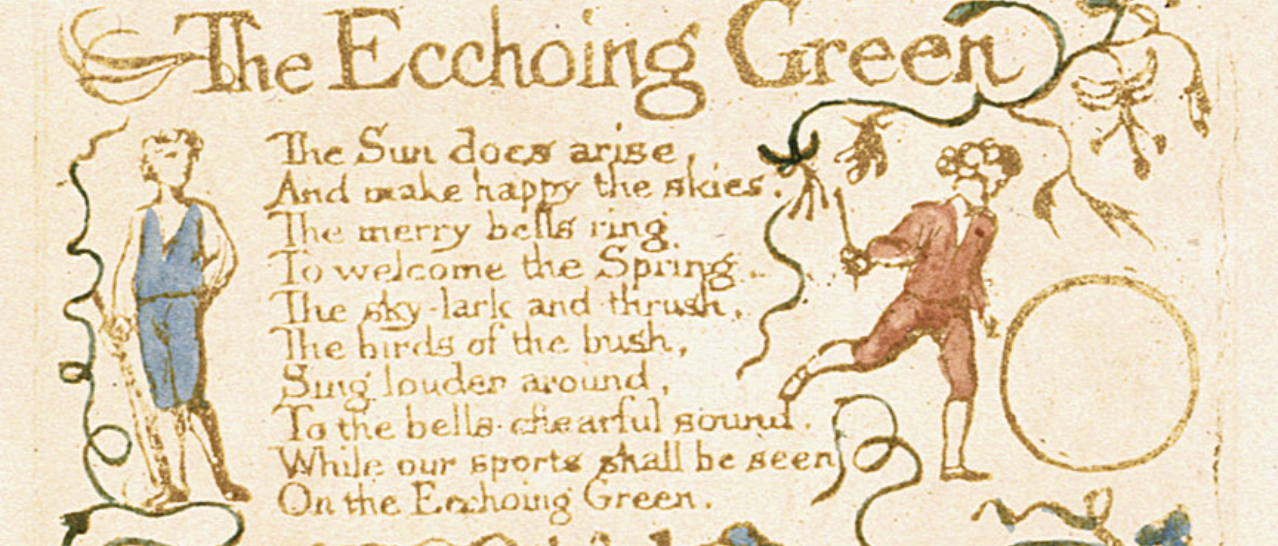

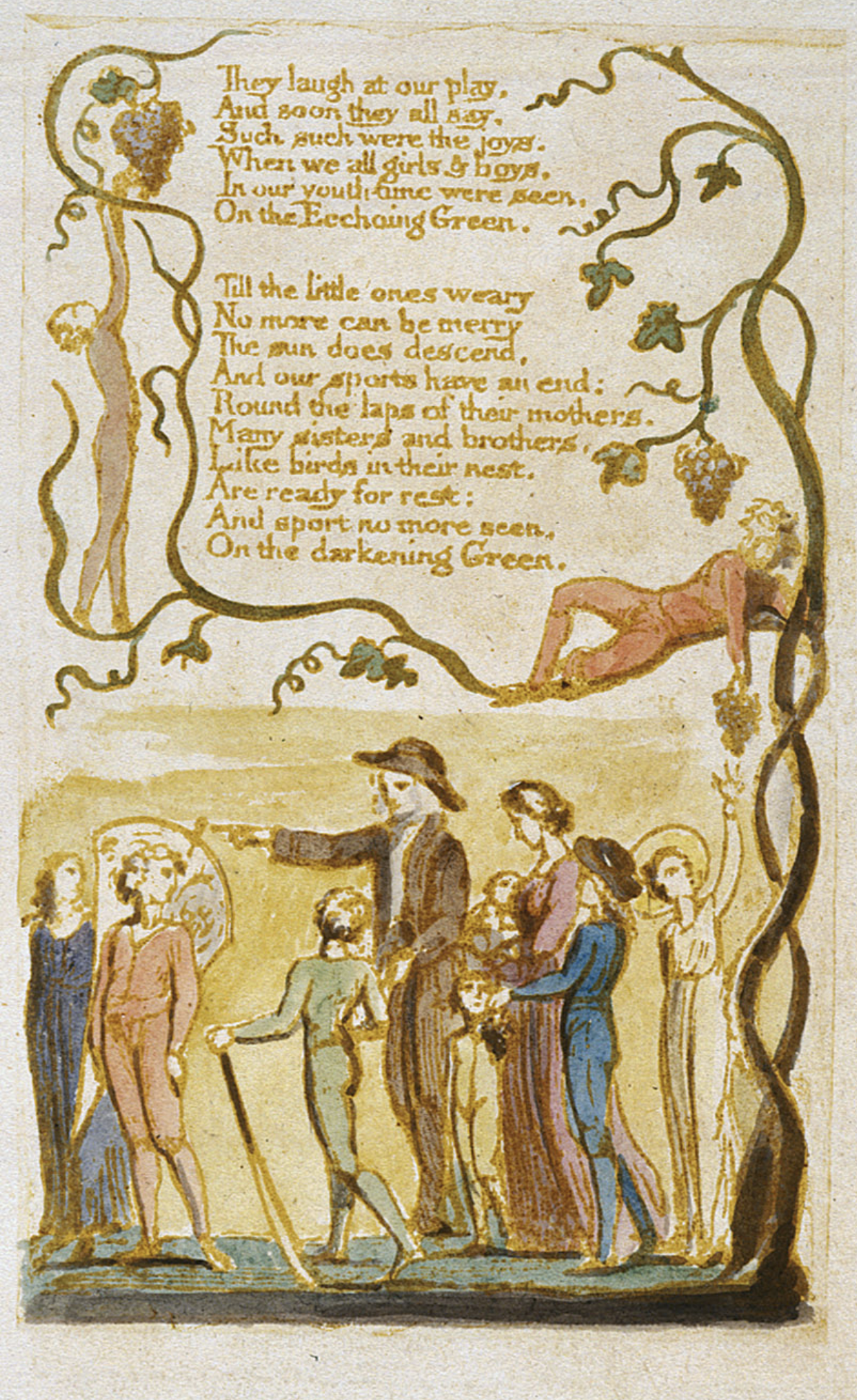

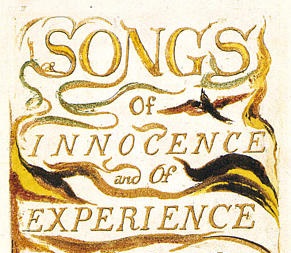

The kids filed into the classroom chatting with each other, then curiously eyed me and the image of “The Ecchoing Green” projected on the board. Taking a deep breath, I started off with some history on Blake and his profession as an engraver, and to my surprise, they were actually paying attention. Most of them were impressed by his fancy font and intricate images, and duly impressed when I explained that he had to engrave his text and images backward on copper plates, so they’d print correctly.

We focused on how the poem employs its setting and characters: the field the children play in could represent the space in life that requires action and participation. The games played in that space can be executed fairly and with foresight, or poorly and with shortsighted judgment. The title might even refer to the fact that decisions made at an early point in life have an echoing effect on later years. My aim was not interpretive accuracy; deriving a simple, clean-cut moral theme from a text was still an important takeaway. I wanted them to see this poem from a personal perspective–which is not a natural instinct for kids who’d rather be playing actual games.

But, their ready engagement was a welcome surprise and not difficult to foster, thanks to the multimedia nature of Blake’s work. I hadn’t really thought about how the kids’ idea of poetry might be pleasantly interrupted by Blake; this was not a poem made of boring black words on a white background in a thick anthology—a presentation that brings immediate resistance to young readers. His poetic music and rhyme scheme quickly caught their ears while the bright illustrations made this poem stand out from most of what they had read before.

Because of all this, I don’t think I could have chosen better than Blake. Early middle schoolers aren’t used to thinking abstractly quite yet, and while they might be too mature for the picture books of their younger years, that doesn’t mean they’ve completely outgrown those learning devices. With picture books, kids are trained to rely on images before words, so seeing Blake’s print gave them a definite foothold. Unlike picture books, there’s substance in a poem like “The Ecchoing Green” that they can sink their teeth into. Looking at Blake’s layers of text, image, and design as a scholar reveals infinite complexity. But looking at it as a kid, we’re brought a little closer to the magic and immediacy of his poetic experience.

By the time I’d finished teaching the second class and the students were quietly (more or less) scribbling away at a worksheet, I wasn’t sweating the third and final group. I probably should have. Out of the blue, my mom was called away on official business with an admin, which meant I’d be on my own with the difficult class, who’d be on a sugar-high fresh from lunch hour.

The kids tumbled into the classroom from the passing period, took one glance at me, and continued unperturbed in loud conversation right through the bell. The first few minutes were sink-or-swim and the echoing green before me was on the brink of unsalvageable chaos. So I mustered my best “teacher voice” (wasn’t even sure I had one of those) and made them sit down and get to work. The effect wasn’t perfect; they sustained a suspicious and insatiable chorus of whispering throughout the lesson that I couldn’t fully shut down. But despite feeling like I was trying to keep thirty-plus corks underwater at once, we did get through the whole thing with an on-topic discussion and class participation.

My mother came into the room fifteen minutes before class ended, and everyone fell into a tense silence. She requested, with narrowed eyes and the sort of ice in her voice that made my childhood flash before my eyes, that they all return to their assigned seats. That’s why they couldn’t stay quiet—they were all sitting by their friends. There was a great shuffling of chairs and papers as the students scrambled to move and I looked down to hide a laugh. It’s the oldest trick in the book, and I didn’t even think to look for a seating chart when I took attendance.

After my mom ushered the ring leaders into the hall for interrogation, a few of the students came up and apologized to me–which was pretty cute. Not much harm was done, and I reasoned that some lessons are just as well learned through experience as they are in innocence.