This semester I enrolled in a course entitled “Digital History: Historical Worlds, Virtual Worlds, Virtual Museums”— thoroughly intrigued by the course’s description which promised to teach me to “harness emerging technologies to educate the public about the past.” It seemed familiar, yet distant enough from my existing skill set to be rewarding.

And I very quickly found out how right I was. Within the first week, we were immersed in texts that discussed the real world, real applications of virtual worlds and video games. In the second week, we were abreast of all the educational historical games on the web and the differences (good or bad) between them. And in the third week, we were spending class periods—and weekends—debating the pros and cons of scores of topics that we would collectively have to narrow down to one, and then commence spending a semester developing it into an interactive, educational, and fun virtual game.

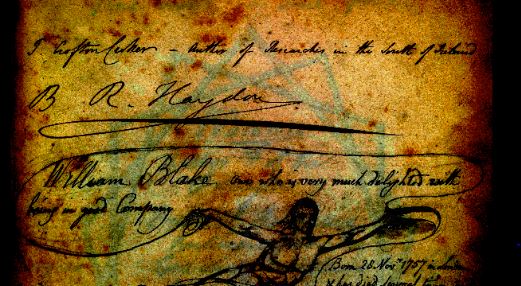

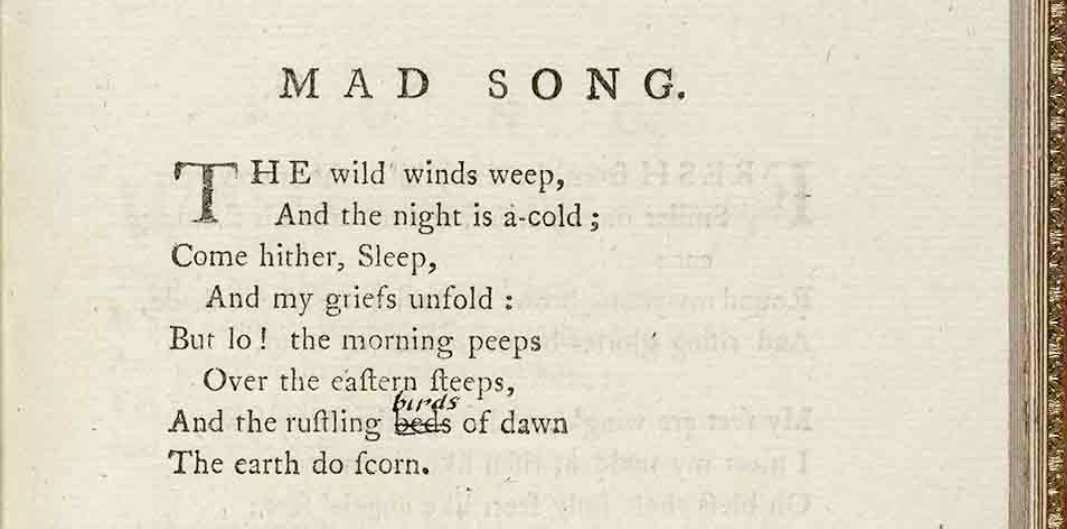

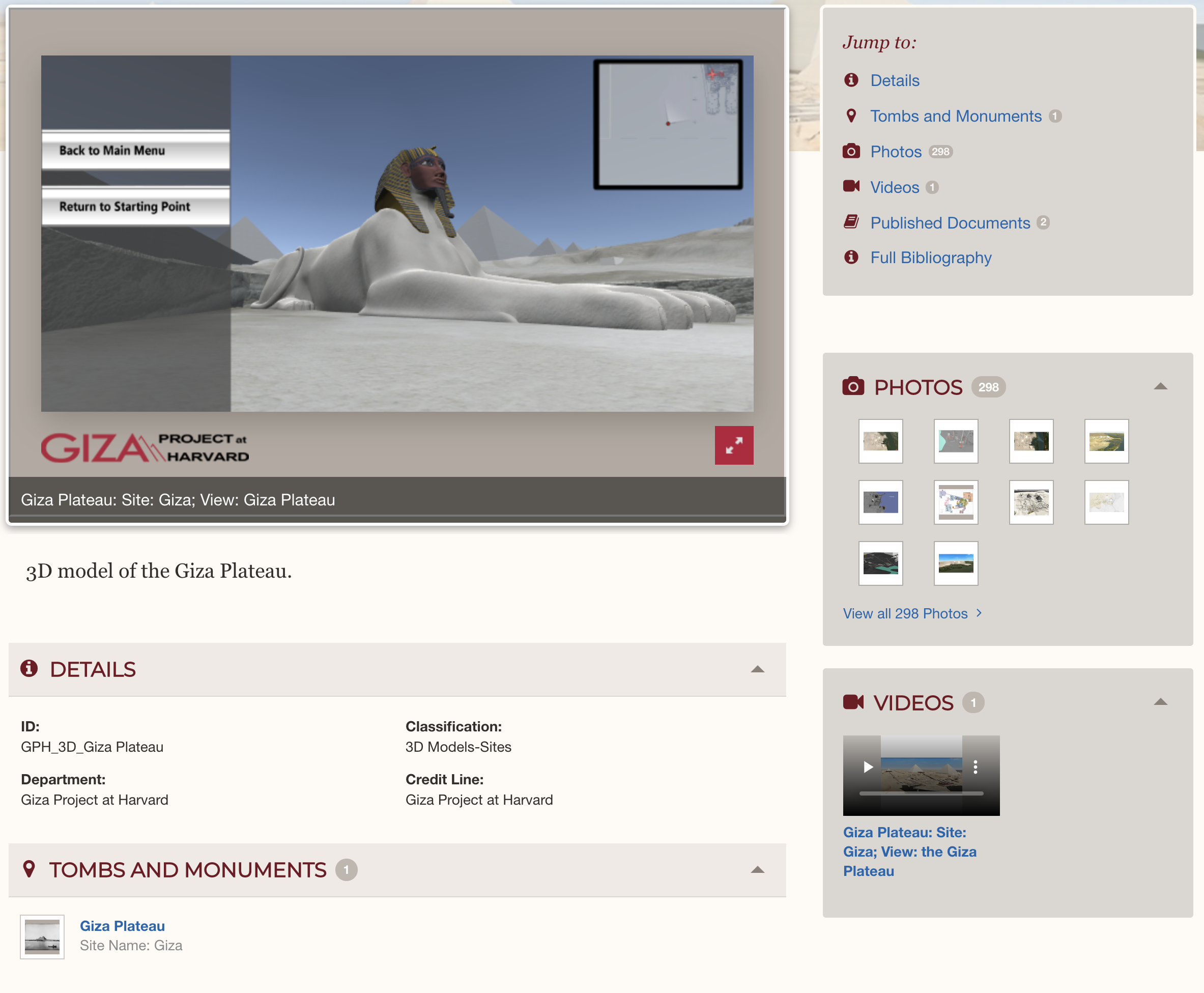

I led the topic-charge boldly and confidently: recreating the interior of Blake’s apartment and studio would surely be interesting and educational to users worldwide. Having spent a portion of last semester’s course on “Radical Romantic Critical Theorists” with Morris learning about Blake’s complex illuminated printing process, I thought there was a phenomenal opportunity to depict that process through an interactive, digital recreation of his studio in Lambeth. Users could see works like The Songs of Innocence and of Experience and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell come to fruition through a matter of clicks, rather than having to buy a plane ticket to visit them personally or procure a variety of supplies and know-how to try and recreate the process themselves. Furthermore, the Blake Archive team could contribute to, help with, and support the creation of the project—it seemed like a perfect collision between my digital humanities worlds.

My classmates, however, were not so enchanted by what promised to be a significantly intricate and complex project, and Blake quickly, dishearteningly, fell to the wayside.

We explored a number of other topics afterwards: Fort Niagara, Kodak, Downtown Rochester, ancient Greece, the Erie Canal, the Rush Rhees Library, and each was turned down—some were too local, some too niche, and others just seemed to lack wide appeal. Then, after discussing how covering the Rush Rhees Library could potentially lead us to explore its mysterious underground bomb shelter (which later, it turned out, is apocryphal), our professor, Dr. Michael Jarvis, interjected: “What about Bermuda?” To which we all internally responded, “What about Bermuda?” And then, after much exploration of the country’s serendipitous founding through the fantastic story of the Sea Venture and its crew, we confidently echoed our professor: “What about Bermuda!”

And just now—five, six, seven weeks into the semester (I refrain from counting as it reminds me of the looming seminar paper due dates)—we have some semblance of a digital historical project: a text-based survival game that has users select from different historical and ahistorical options to determine if the Sea Venture and its company would’ve survived a level-5 hurricane, a crash-landing on a distant island, and a return to the dying, flesh-fed Jamestown Colony under their command.

And though it isn’t Kodak, or the apocryphal Rush Rhees bomb shelter, or anything close to the intricate and eccentric artistry of William Blake (in other words: not at all anything I’m usually interested in), I’ve found that it’s phenomenally intriguing nonetheless. When we’re working, we’re learning fantastic things: the story of a ship that saved the colonization of America, the intricate—and sometimes mutinous—histories of the passengers on board, and, more pragmatically, how to write about these things with an eye towards the public, how to make them interesting yet educational, how to code them into gameplay, how to represent and misrepresent history…! In other words, when we’re working, we’re learning no longer just for ourselves, but for the sake of enthusiastically sharing that knowledge with others.

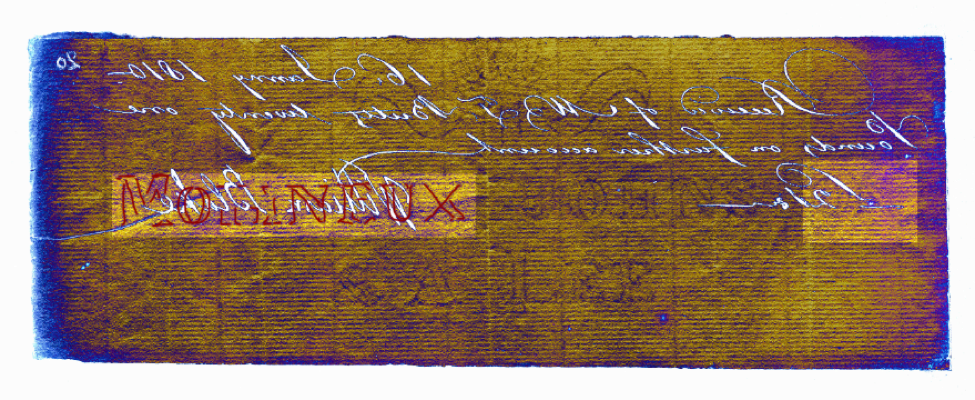

Through all of this—the topic debating, the platform determining, the gameplay discussing, the project managing, the script writing, the frustrated messaging, the researching upon researching, and the designing—I’ve quickly learned that a lot goes into creating digital projects. And through the Blake Archive (and its weekly meetings, and office hours, and script [hand and code] decoding, and proofing sessions, and topic lessons, and cross-country communications) I’ve learned that a lot goes into maintaining digital projects.

And still, as I send another message to my Digital History group; and still, as I update yet another document about the crew of the Sea Venture; and still, as I head to my office hours to become a part of Blake’s French Revolution once more; and still, as I write a blog post amidst piles of assigned readings—I find that there is nothing more rewarding than getting digital, getting historical, and sharing the products of those efforts with the world.