This post is the third in a series of interviews by S. Yarberry—the others were with Aditi Machado and S. Brook Corfman. S. approached us with the idea of interviewing poets about Blake and his infuence on their work: “I’m interested in bridging contemporary poetry with the academic study of Blake—academia and creative circles sometimes sit so far apart that we forget how much common language we have.” The interview has been lightly edited for style. Bios. are at the end of the post.

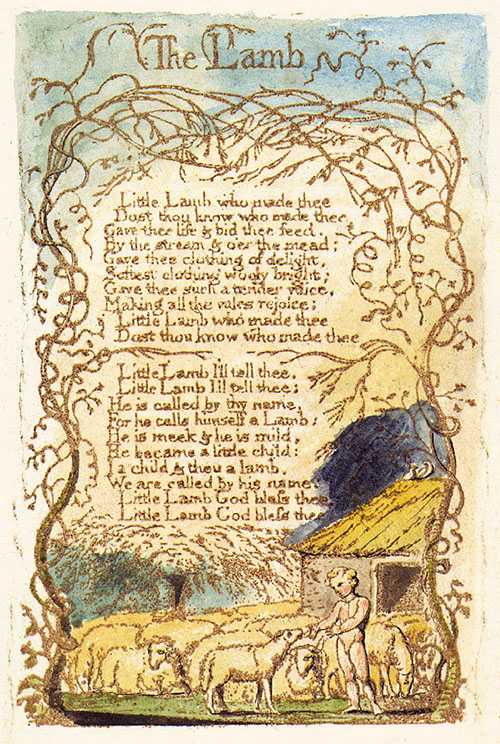

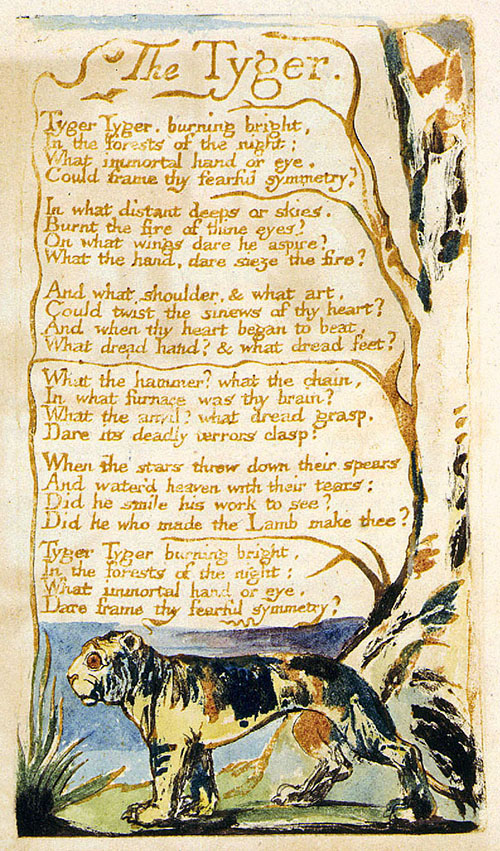

In a great—short but sweet—podcast on “The Lamb” and “The Tyger” (on the Zoamorphosis blog), Jason Whittaker argues that the “spiritual vision [of “The Lamb”] is much less startling than that of the later song [“The Tyger”].” And this is true. “The Lamb” is anything but startling. The conversation, by Blake’s design, is quiet and predictable.

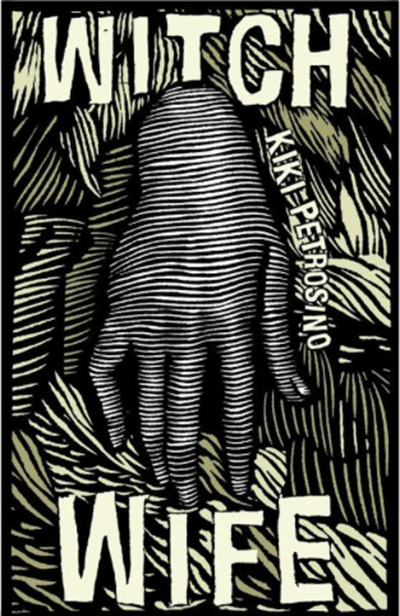

Kiki Petrosino’s poem “Self-Portrait” has the energy of “The Tyger” in the form of “The Lamb.” You can read it online via River Styx magazine or in her collection Witch Wife (Sarabande Books, 2017). The poem startles. It activates the sense of being seen, even if you cannot pinpoint how or what exactly is exposed.

In the podcast, Whittaker goes on to say that the child in Blake’s poem interacts with the lamb based on instinct rather than logic; similarly, Petrosino’s speaker eschews reason for intuition. Petrosino also flexes the power of prosody. She uses sound and meter to knit together images of algae, wool, and lichen—of pigs, palms, and poison.

Although Blake probably did not see “The Lamb” and its sibling poem as self-portraits, we, his readers, have used these poems as snapshots of the Blakean mind. Whittaker comments that “the beauty of ‘The Lamb’ is its simplicity.” Perhaps, then, the beauty in Petrosino’s poem is its vicious slipperiness: the beauty and horror of the body, and the experience of that body.

S. Yarberry: To start us off, what interests you in the work of William Blake, his poem “The Lamb,” and/or Songs of Innocence and of Experience more broadly?

Kiki Petrosino: I am certainly not an expert on William Blake, but I remember reading his work as a young student—specifically during my undergraduate career. Blake is one of those poets whom you encounter at length, in a deep way, when you’re an English major. So during my undergraduate education I read the entirety of the Songs of Innocence and of Experience, and also [William Carlos Williams’s] Kora in Hell. However, I remember that much less vividly than the Songs. We looked at the prints and I remember the color variations, these very strange etchings that Blake did to go with his poems. He stands out to me as a poet who incorporated the visual with his texts. He is presented as an innovative, very eccentric, and miracular mystic who could also painstakingly make all of these etchings, etchings that could embed and maintain these poems. There is also a lot about Blake’s music that is really memorable and indelible to the ear. I think of him too as a very skilled technician when it comes to sound.

SY: Speaking of sound, let’s move to your poem “Self-Portrait,” which appears in your most recent collection, Witch Wife. You have “The Lamb” as what I have been calling an underlay to your own poem. And by that, I mean that you keep a fair amount of the syntactic structures, the rhyme scheme, the form, and the antiquated diction, so “The Lamb” is very present—if readers know that poem. Why did you pick the “The Lamb” as a means to write a self-portrait poem? Was that always your intention or did you find yourself suddenly falling into a self-portrait when working with the Blake poem?

KP: “The Lamb” is really interesting because it is as much about, or really more about, the questioner—the speaker who is speaking to the lamb—than it is about the actual lamb. In the poem the speaker is questioning the lamb to find out what, or who, made the lamb—who gave “thee” all the attributes of a lamb. There’s a tension in the poem about what is being depicted—are we actually supposed to leave the poem with a picture of a lamb, or are we getting a picture, some kind of sketch, of this very insistent, plaintive speaker, who is not a lamb and who is also not God, but who wants answers about God? The speaker performs a kind of haranguing—is it a plaint toward the divine? I think that it is, so we find out more about the speaker’s preoccupations. That said, in my poem there is a tension between the speaker who is asking questions and the “you” who has all of these things attributed to her by that speaker. I thought it would be interesting to construct a self-portrait out of that tension—you don’t really know whom you are actually looking at in the poem.

SY: I have read “The Lamb,” of course, many times, but after reading your poem I revisited it in a deeper way than I had in a long time. You know it’s one of Blake’s best-known poems and I had written it off as this kind of Jesus-y-pastoral poem. But upon returning to it with “Self-Portrait” in mind—as you’re saying—there is a provocative tension between the speaker and the addressee. In the opening lines to “Self-Portrait” you riff off Blake’s lines:

Little Lamb who made thee

Dost thou know who made thee

and you change the lines to:

Little gal, who knit thee?

Dost thou know who knit thee?

I am particularly interested in the verb change from made to knit. Can you talk about that decision? I am wondering, too, if you could talk about what you did decide to keep from the Blake poem and what you decided to change—and how you came up with the lexicon of imagery and language for the poem.

KP: You can see that I kept the lineation and the contours of the address from Blake. I also kept the “thee” construction for “you” because it sounds so strange and ornate and almost alien to say “thee.” I know that there are communities that have that in their spoken language, but it’s not a part of my spoken language. I liked bringing it in since it sounds odd to a certain ear—it signifies a speaker who comes from a slightly different world. That’s what I wanted to signal to the reader in this particular poem. The verb “to knit” in some sense is biblical. There is at least one translation of the Bible in which God says, “For you created my inmost being; you knit me together in my mother’s womb” (Psalm 139). I am not even sure how that translation came to be—I’m sure there’s an interesting backstory to it. I thought that intentionally knitting, making something was not only a cool idea, but also something you can connect really strongly to the idea of a self-portrait. A self-portrait is something made with intention—it is crafted with some sort of medium.

SY: I am really interested in the idea of knitting a persona, knitting a version of the self. In my mind, I envision knitting as an ability to see those movements, those decisions, in a more tactile way. You brought up the form of “The Lamb,” and you have talked about your interest in form—fixed forms—in other interviews about Witch Wife. “The Lamb” has a kind of peculiar shape and prosody to it. Or were you more interested in “The Lamb” for the content and symbolic resonance?

KP: I think both. I write as much by ear as I do by brain. Or by mind. Or by eye. Poems that are memorable to me are poems that have a memorable rhythm, a memorable meter, like the work of Blake. “The Lamb” is a poem I read and studied early on in my career as a poet—and so those early poems become almost part of a shared language with other poets as well as what you share within the English language. That’s why it is important as a teacher—side note—to select poems for young people to read. There are a lot of changes happening now with these canonical works: what work do we take into 2019 and beyond with us? And rescue from being canceled, as it were. And what new voices do we also carry along with us? Because those newer voices, voices of color, women, LGBTQ+ voices, are also in many ways in dialogue with these older voices. While I write poems as an African American woman poet, I am still aware of Blake and I still hear Blake; I hear his rhythms and the other things that I have studied. But I still want to respond and draw out what I hear, what I see in his poems. The idea of the intentional artist—the idea of self-consciousness and self-creation—is extremely relevant today, when we think about branding, personal-branding, social media, and how we are encouraged through these platforms to construct a self that can then stand in as an avatar for our actual self. The lamb in Blake’s poem is just being a lamb. The lamb’s beauty, the lamb’s innocence are supposed to signify something about its creator. It is supposed to be some kind of argument by the creator for something and the speaker of the poem wants to know what that something is. We can ask the same questions about our various social media presences, but we know who made those things: we made them. As a writer, you can try to complicate the issue of intentionality by responding to an older work, which is what I did with “The Lamb.”

SY: I like the idea of our social media accounts being self-portraits that we are making all the time. I think picking something like “The Lamb,” that, as you are saying, is very canonical, and giving it this sort of remodel is, for lack of a better word, quite awesome. Another thing I find notable is the intertwining of imagery and language around youth—“little gal” and “I am nimble. I am young”—and the language of viciousness—“vicious lungs,” “Stuffed thy brain with blooms of blight”—and so the poem then moves between the ideas of innocence and experience. It’s a poem that fits into both of those realms—or, perhaps, weaves in and out of them. Can you talk about how the concepts of innocence and experience influenced your writing of this poem?

KP: That book, Witch Wife, is really personal in the sense that I feel like the speakers of the poems are very closely aligned with me and my own journey. Many of the poems look back on adolescence and early adulthood. They are retrospective in some ways and are asking, was that really the way it was? The way that I remembered something or the way that I responded to it at the time—I suppose the speaker is asking, were those responses the right ones? In the case of an early heartbreak, did I respond, did the speaker respond, in the way that we would today? Looking back on it, are those experiences always the same in your mind when you think about them now?

SY: The interview that I did before this one, with S. Brook Corfman, brought up a similar idea—not necessarily a distrust of childhood memory, but definitely a reconsidering of what actually happened in those childhood moments. It’s interesting that Blake’s work in Songs sparks the desire to go back and think, what are my childhood poems? What was my childhood actually like versus what I remember it to be? And, of course, not actually being able to access that memory, or those truths, but really wanting to. “The Tyger” is, of course, the “sibling” poem to “The Lamb” and the two are often talked about in unison. Were you thinking at all about that poem?

KP: Yes, I did think about that poem. It’s a beautiful one and a great companion, or response, to the questions of “The Lamb.” In many ways the questions are the same, but just more darkly asked. The climax is when the poem asks, “Did he who made the Lamb make thee?” We, the readers, at least in this cultural context, and in Blake’s cultural context too, know the answer is “yes.” The poem celebrates the beauty of the tiger. A lot of the most vivid language comes out of describing how the tiger moves through the forests of the night. It’s another poem that seems pretty simple in construction, but that kind of song form that contains within it a lot of the lyric energy is actually very complicated—that unfolds throughout the poem—especially when you read it next to “The Lamb.”

SY: Speaking of the lyric energy of the poem—I noticed you wrote “Self-Portrait,” for the most part, in a trochaic meter. What was that experience like?

KP: I didn’t think about it too much. Once you start writing in it, it becomes a very propulsive mode. It doesn’t feel unnatural at all—you start to bounce along with it.

SY: Another question I have is about the placement of “Self-Portrait” in Witch Wife. It’s the first poem in the collection. It is a self-portrait poem—so having it first makes sense in many ways. And for those readers who recognize the Blake poem they will probably carry that poem with them at least for part of the reading experience of the collection. Can you talk about your choice to put this poem at the forefront?

KP: I had first conceived of Witch Wife as a book that would be all self-portraits. And I really do feel that all these poems are self-portraits in some way or another. Therefore, I liked starting with a portrait where the speaker doesn’t actually give a lot of attributes to the figure except through references to other poets, such as Blake and, at the end of the poem, there’s a reference to Elizabeth Bishop—“long pig,” which comes from her poem “In the Waiting Room.” In that poem, a young person is coming of age and encounters, in National Geographic, images of unclothed tribal people engaging in some sort of ritual. The speaker in the Bishop poem compares the naked human body, in its mystery and vulnerability, to a “long pig.” The idea in the Bishop poem is that the body is a long pig. That said, the speaker in that poem is contending with all the visceral nature of the body—and is realizing that she has a body, she has a female body, that it will become like all the bodies of the grown women she sees around her. There are also some ideas of race and class in that poem that may not be as fully realized as we would ask them to be in 2019. To me it’s a poem that is about body image, or it can be, or I find a reading with that in it when I read it. Going back to my poem, it’s kind of a self-portrait made up of other poets’ self-portraits.

S. Yarberry is a trans poet and writer. Their poetry has appeared in, or is forthcoming in, Tin House, Indiana Review, the Offing, Berkeley Poetry Review, jubilat, the Washington Post’s Lily magazine, Notre Dame Review, Nat. Brut, DREGINALD, Burnside Review, and miscellaneous zines. Their other writings can be found in Bomb magazine and forthcoming in Zoamorphosis. S. has an MFA in Poetry from Washington University in St. Louis, where they now hold the Junior Fellowship in Poetry. They currently serve as the poetry editor of the Spectacle.

Kiki Petrosino is the author of three books of poetry: Witch Wife (2017), Hymn for the Black Terrific (2013), and Fort Red Border (2009), all from Sarabande Books. She holds graduate degrees from the University of Chicago and the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Her poems and essays have appeared in Poetry, Best American Poetry, the Nation, the New York Times, FENCE, Gulf Coast, jubilat, Tin House, and online at Ploughshares. In fall 2019, she will begin teaching at the University of Virginia as a professor of poetry. Petrosino is the recipient of a Pushcart Prize, a Fellowship in Creative Writing from the National Endowment for the Arts, and an Al Smith Fellowship Award from the Kentucky Arts Council.