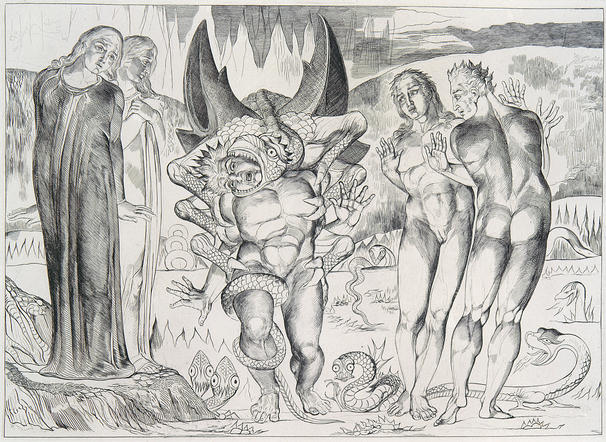

Back in January as everyone slowly made their way back to campus here at UNC, Blake Archive editor Joe Viscomi and I had a chat in one of the Archive offices. After talking about our winter break and our plans for the spring semester, the conversation of course turned to Blake. A framed Blake Trust facsimile reproduction of one of Blake’s illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy hanging on the wall caught our attention. The image shows a dragon or serpent attacking the thief Agnolo Brunelleschi.

Our discussion turned from the serpent in this illustration to Blake’s depiction of serpents more generally. Serpents wrapped around the torsos or legs of human figures are common motifs in Blake’s artwork, and some of the more famous examples come from his biblical scenes, particularly his illustrations of the events leading up to the temptation of Adam and Eve.

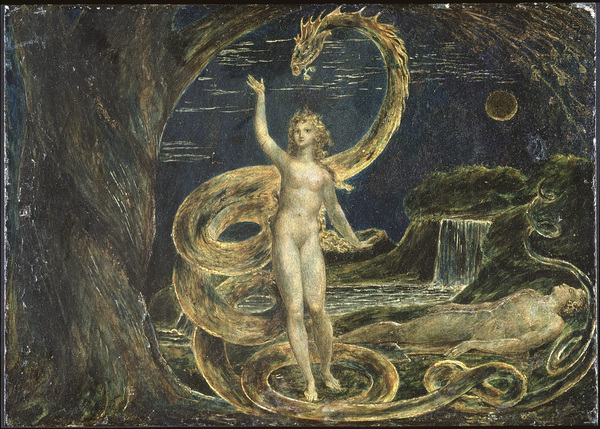

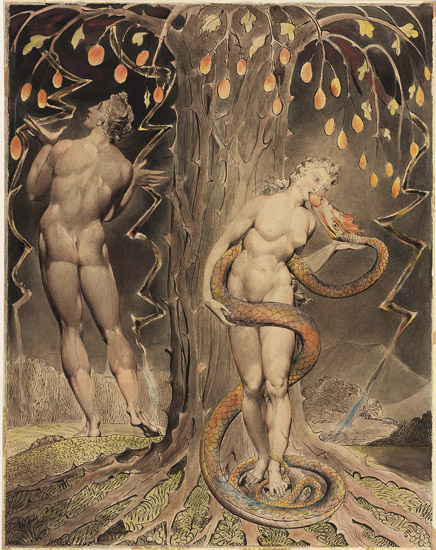

Of course, the serpent is a nearly ubiquitous image in Christian iconography as a representation of Satan, particularly in Eden scenes. Imagine any painting of the temptation and there’s a good chance that Satan as serpent will be in it, perhaps wrapped around the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. Throughout his body of work, Blake depicts the temptation scene several times, and Satan is usually presented as a serpent, although Blake often wraps the serpent around Eve instead of the tree. Take for example Eve Tempted by the Serpent or The Temptation and Fall of Eve.

Having the serpent coiled around Eve instead of the tree makes for a much more sexualized temptation scene in both of these images. This is especially true in the second, in which the two figures eat from the same apple, Lady and the Tramp style. In both images Adam is also oblivious, making the temptation particularly illicit, like an affair.

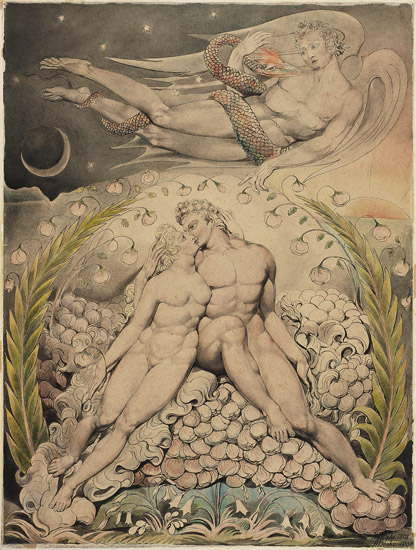

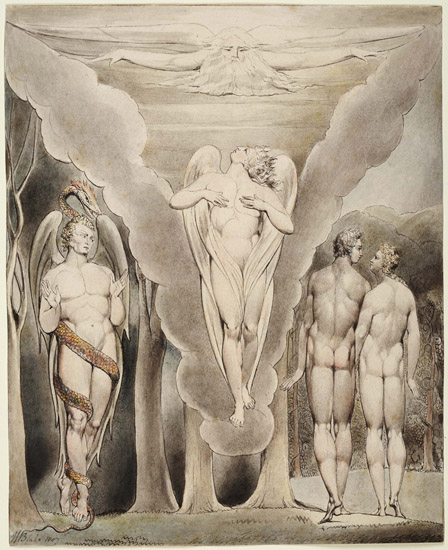

In other images, Blake’s use of the serpent differs even farther from iconographic tradition, as Joe pointed out. He said, “You rarely see depictions of both Satan and the serpent in the same image before Blake.” Although the serpent often has a woman’s face or even a female upper body pre-Blake, images of a full-bodied Satan and the serpent are not as common. Blake plays with this tradition by including both forms in many of his images, such as Satan Watching the Endearments of Adam and Eve from the Butts set of Paradise Lost illustrations.

Viewing this image makes one question why Blake would include both forms of Satan. In this case, I think the sexualization of the serpent offers some explanation. The serpent wraps around Satan, covers his genitals, and becomes a phallus. Satan strokes the serpent’s head and stares into his eyes longingly, mirroring the sensual stare of Adam and Eve below. Finally, Satan points to the couple, in a gesture of covetous desire. By including the serpent, Blake heightens Satan’s sexual voyeurism in this scene.

However, the use of both the serpent and angel forms of Satan in the same image is not always so overtly sexual. Take for example Satan Spying on Adam and Eve and Raphael’s Descent into Paradise, the image that immediately precedes Satan Watching the Endearments of Adam and Eve in the Thomas set of illustrations. Here, the serpent still coils around Satan’s body and covers his genitals. However, the two are not looking into each other’s eyes, but are both staring at Adam and Eve. Their gazes here seem to be less sensual and more aggressive, as if they’re sizing up an opponent. The serpent even has its head reared back ready to strike.

In both this image and my previous example, the serpent and angel forms of Satan mirror and amplify the emotions of the other, whether that be sexual desire or defensive aggression. In this way, the serpent acts much like a daemon from Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy, serving as a pseudo-soul which provides insight into Satan’s motives and mental state.

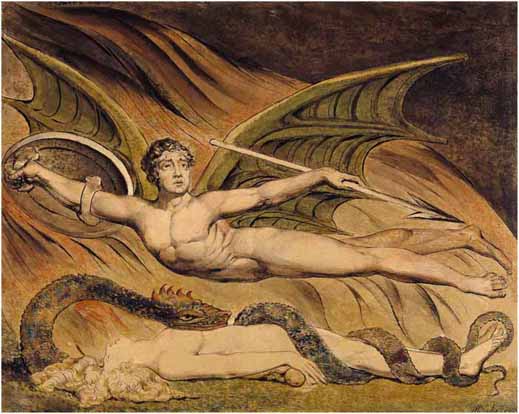

Satan Exulting Over Eve—which predates my last three examples by twelve or more years—separates the two forms instead of coiling the serpent around the angelic Satan. However, even with the separation, the image still maintains a daemonic link between the two forms. Here, Satan flies over an unconscious Eve in full regalia celebrating his victory and guarding his prey. The serpent mirrors Satan by coiling around Eve, emphasizing possession of and control over her. The coiling serpent and nude Satan might also carry sexual tones, but both figures are looking at someone or something out of the frame instead of at Eve. Therefore, the lack of sensual gaze makes the scene overall less sexualized than might be expected.

As I mentioned earlier, Satan is far from the only character that Blake depicts alongside serpents. For instance, in an illustration to Job, he coils a serpent around the hoofed false God of Job’s vision. There is also the scene from Dante’s Divine Comedy that sparked my conversation with Joe to begin with. However, the Satan-serpent pair is an image familiar to most readers, and thinking about that pairing in Blake can lead us to consider how he experiments with artistic precedents and traditions.

Excellent but it would be even more interesting to relate Blake’s Satanic imagery to our own spiritual problems and to those of present day society.