Chris Hobson wrote the main article, “Blake, Paul, and Sexual Antinomianism,” in the winter 2018–19 issue of Blake. In the course of our correspondence he told me that he’d just published James Baldwin and the Heavenly City: Prophecy, Apocalypse, and Doubt, and that he sees Baldwin and Blake “as very similar figures despite the obvious differences in century, nationality, race. They share ideas of social change adapted from Revelation (for each, the central Bible text), as well as on sexuality and a rejection of false holiness.” Thus the germ of this Q&A was planted; many thanks to Chris for taking part.

Which author did you encounter first, and what are the themes their works share that are of interest to you?

I read Baldwin first, starting with The Fire Next Time on publication (1963), then Giovanni’s Room (extremely influential for me) a year or so later, then Another Country—Baldwin’s breakout 1962 social conflict novel—a couple of years after that. I didn’t read the rest of Baldwin until the 1980s, and, except for some of the Songs, I hadn’t read Blake seriously until then. So I read a good part of each author more or less in the same period. I was struck by how many central issues they shared: social conflict and possible liberation, understood in biblical and apocalyptic terms; sexuality, the holiness of the body, and hostility to moral law; prophecy as a literary mode. (A real understanding of the religious ideas in both came more gradually.) That two such writers so widely separated in time and background cultures share so much has long fascinated me. The commonalities extend even to secondary matters—for example, Baldwin uses “the righteous” and “the damned” in If Beale Street Could Talk, his fifth novel, almost exactly in the inverted, ironic-polemical way Blake uses “the Elect” and “the Reprobate” in Milton. Yet, judging from actual quotations, Baldwin knew little of Blake besides some Songs, “Auguries of Innocence,” and (importantly) “The Everlasting Gospel”—some of the more accessible works found in an anthology such as Alfred Kazin’s The Portable Blake (1946).

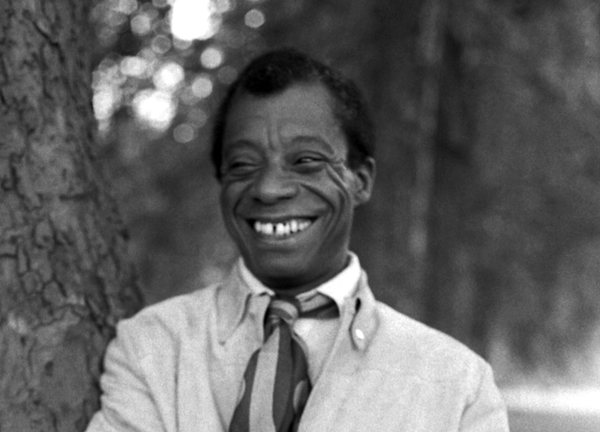

Attribution: Allan Warren [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)].

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:James_Baldwin_08_Allan_Warren.jpg.

How does Baldwin’s religious background compare to Blake’s?

It’s different. Blake, we know, had the Church of England as a primary reference, and may have been influenced by various earlier and contemporary antinomian and “enthusiastic” currents, including his mother’s Moravian history. Baldwin’s family were Baptists and he was lastingly influenced as a teenager by African-American Holiness and Pentecostal churches, in which he was briefly a youth preacher. He probably knew next to nothing of the currents that have been theorized as influential for Blake. The Holiness-Pentecostal theologies descend from John Wesley’s Methodism, but Wesley was notably non-apocalyptic—these theologies added their apocalypticism, so influential for Baldwin, much later—and Wesley was also sexually very conventional. It wasn’t easy, in other words, to account for the similarities I saw on the basis of a common religious heritage.

Your recent article discusses ways in which Blake revises and challenges Paul’s teachings. How does Baldwin use the Bible?

That is one of the resemblances I see. They use the Bible—meaning the King James or Authorized Version for both—in some very similar ways. Most specifically, the centrality of Paul in Christian sexual ethics is a point of connection. Baldwin, I argue in my book, gets to his sense of the body’s holiness by rejecting Paul’s flesh-spirit dualism but also by appropriating Paul’s teaching that God favors the world’s despised, much as, in my article, I argue that Blake both contested and appropriated Paul. More generally, both use biblical (and for Baldwin, gospel music) references everywhere; both structure their works around the Christian pattern of Eden, fall, redemption, and apocalypse; they use some of the same books and even the same passages, such as the Valley of Bones in Ezekiel. And both contrast a liberatory potential in the Bible—a counter-tradition, which is why Baldwin’s knowledge of “The Everlasting Gospel” is important—to actual church practice. Baldwin, however, is not a believer as an adult, so these uses of the Bible are analogies for him, but with a genuine holiness at their core.

How would Baldwin react to Blake’s statement that everything that lives is holy?

In Another Country, Reverend Foster, a Harlem minister, is speaking the elegy for Rufus, a major character who has committed suicide. In reference to the idea that suicides shouldn’t be buried in holy ground, he says, “All I know, God made every bit of ground I ever walked on, and everything God made is holy.” Rev. Foster is talking only of this one issue, yet he is stating a deep belief. Readers, however, have an additional dimension, since they know, as Rev. Foster doesn’t, that an hour or so before he died, Rufus was standing at a urinal, “holding that most despised part of himself loosely between two fingers of one hand.” For readers, Rev. Foster’s words make the same point that the body’s sacredness must not be despised that Blake is making with his words, whether in America, Marriage, or Visions, and this is, in the whole context of Baldwin’s novel, a central thematic point. I think, then, that Baldwin not only would approve Blake’s formula, but replicates it. It’s possible he remembers it from some reading of one of these works; he never quotes it directly.

Do you see parallels between the evolution of Blake’s and Baldwin’s ideas?

Some parallels, yes. For instance, both begin as religious iconoclasts—Go Tell It on the Mountain, Baldwin’s first novel, is quite commonly read as declaring his opposition to Christianity, much as Marriage, Urizen, and other early Blake works expose religious hypocrisy and power-seeking. Both later make a kind of truce with the religious attitudes of ordinary people. Both also begin with a sense of the holiness of the body and sexuality, which Giovanni’s Room, Baldwin’s second novel, emphasizes with a sudden flood of biblical and sacral language as its protagonist comes to terms with his homosexuality; and both keep this sense, but add to it a later conviction of our deep imperfection. And, finally, both are deeply influenced by living through periods of near-revolutionary social struggle, the 1790s and 1960s respectively, but both later witness the collapse of these struggles and must work to maintain and recalibrate their faiths against temptations of doubt and acceptance of the world as it is.

One theme in your book is a focus on blues and gospel as representing sensibilities in Baldwin’s work. Are there parallels with Blake’s mythology?

A partial parallel. For Baldwin, gospel is the music of transcendent hope and represents, quite directly, the eschatological perspective of the later prophets and the “good news” that is the literal meaning of gospel; blues is the music of life as it is, struggle, betrayal, and endurance, and represents the perspective of the biblical Ketuvim, the Writings in the Jewish Tanakh that deal with the existing world. Baldwin uses gospel quotations along with allusions to Revelation and other New Testament apocalypticism to suggest a possible new world; the similarity between these literary devices and Blake’s depictions of eschatological renewal and an end to the “Covenant of Priam” are clear, though the modes of expression are different. Parallels with Baldwin’s blues are more indirect. Blake’s evocations of ordinary life on the ground, whether in “The Ecchoing Green” or in the injunction in Jerusalem to “attend to the Little-ones” (55.51) are a rough parallel. But for Blake, ordinary life is profoundly divided, partly sustaining and partly terrible and destructive. For Baldwin, the blues bridges this division in a kind of half-rueful, half-joyous recognition of human fallibility, a way to experience daily calamity and, as he says in a 1964 essay on blues, “sort of ride with it.” It’s a very African-American sensibility, and one wouldn’t expect an exact parallel in Blake.

Would the title of your Baldwin book be equally good for Blake if the names were changed?

I love this question! For most of the terms in my title and subtitle—“the Heavenly City,” “Prophecy,” and “Apocalypse”—the application will be plain to Blake people. As for my last term, “Doubt,” in his final novel, Just above My Head, Baldwin dramatizes this idea through the contrasting outlooks of the protagonist, a gospel singer who eventually loses his sense of vocation and the purity of his art, and his brother, the narrator, a worldly skeptic who still desperately needs to believe in the gospel vision. For Blake, I’m finding in ongoing work, the presence of doubt is real, if less obvious. It’s apparent, for example, in the struggle between Los and his Spectre, one that is by no means as triumphal as it may seem. So yes, William Blake and the Heavenly City: Prophecy, Apocalypse, and Doubt—why not?