This post is by S. Yarberry, who approached us with the idea of interviewing poets about Blake and his infuence on their work: “I’m interested in bridging contemporary poetry with the academic study of Blake—academia and creative circles sometimes sit so far apart that we forget how much common language we have.” It has been lightly edited for style. Bios. are at the end of the post.

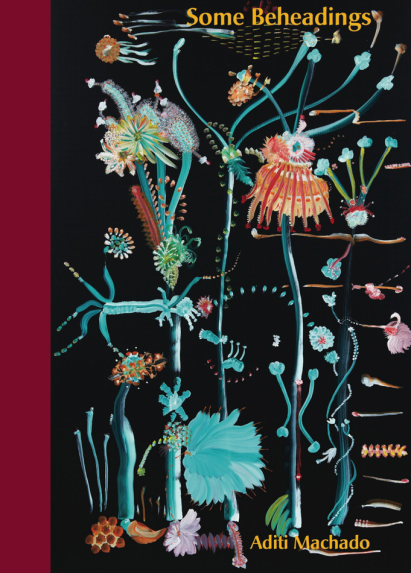

Some Beheadings (Nightboat, 2018) by Aditi Machado is a collection most readily described as labyrinthine—both in where it takes you, but also in how: formally, grammatically, syntactically. In one poem she writes, I thought this was a way a new way. and later she writes, A new way I kept thinking a new grammar of replacement not I / I’d rather be spit. In Some Beheadings I don’t always know where I am going, but I am always pleasantly surprised at where I end up.

The works of William Blake are like this, too—even in poems that appear straightforward, like “The Fly,” there are turns one does not, cannot, expect. Machado and I met up for a cup of coffee in her St. Louis apartment—we sat surrounded by her many books. This interview stems from her poem “If Thought Is,” which can be found in Some Beheadings as well as online at The Offending Adam.

S. Yarberry: What attracted you to the Songs of Innocence and of Experience, and what in particular interested you in “The Fly”?

Aditi Machado: I was reading the Songs at the time I was working on “If Thought Is,” and realizing some exciting possibilities—answers to a question that was troubling me. It was this question of ideas in poetry. Contemporary poetry seemed to suggest that you could have ideas in poetry but only by being impenetrable and “difficult,” or even that the texture of that sort of poetry was cold somehow. The other way to go was emotion and voice, and rampant but somehow restrained subjectivity. I was trying to figure out how to do both: be intellectual and sensuous at the same time. What I found in Blake was exactly that, many times over. He is profoundly philosophical and always very sensory, and his prosodic intelligence is amazing. I don’t have an academic interest in Blake and haven’t read nearly half his writing, but what I have read always has ideas, ideas that are presented vividly and imagistically. Blake helped me realized you could have a sensuous intellect in writing.

For the poem, I borrowed language very straightforwardly from “The Fly,” particularly from the last two stanzas:

If thought is life

And strength and breath,

And the want

Of thought is death,

Then am I

A happy fly,

If I live,

Or if I die.

This connection between thought, life, and death, I found terribly exciting. I know by “want” Blake means the lack of thought is death, but I can’t help also reading “want” as desire. So I end up in this place where thought is both utter vitality while it is also a kind of death. I love these dual imperatives. The other thing I love is the “if” condition, the conclusion of which is:

Then am I

A happy fly,

If I live,

Or if I die.

The happy fly seems to be this tiny happy body flitting around, which is how I like to think about a life of thought—not shut up in an ivory tower.

SY: You’re right—Blake is so confident in stating philosophical comments and then using images to surround these big ideas. He’ll make a lofty statement, which doesn’t necessarily get reduced to an image, per se, but instead gets complicated by the simplicity of an image—like a fly, or a rose. Or a tyger.

AM: Another poet I was beginning to read when I was working on Some Beheadings is the Arab-American poet Etel Adnan. In an interview with Lisa Robertson she says something like “The image is something with which you think.” She’s speaking of Baudelaire and her own work, but it applies to Blake too, I think. It might be that ideas always exist first in art, before they get articulated in other discourses. This might be a contentious thing to say, but so far I believe it.

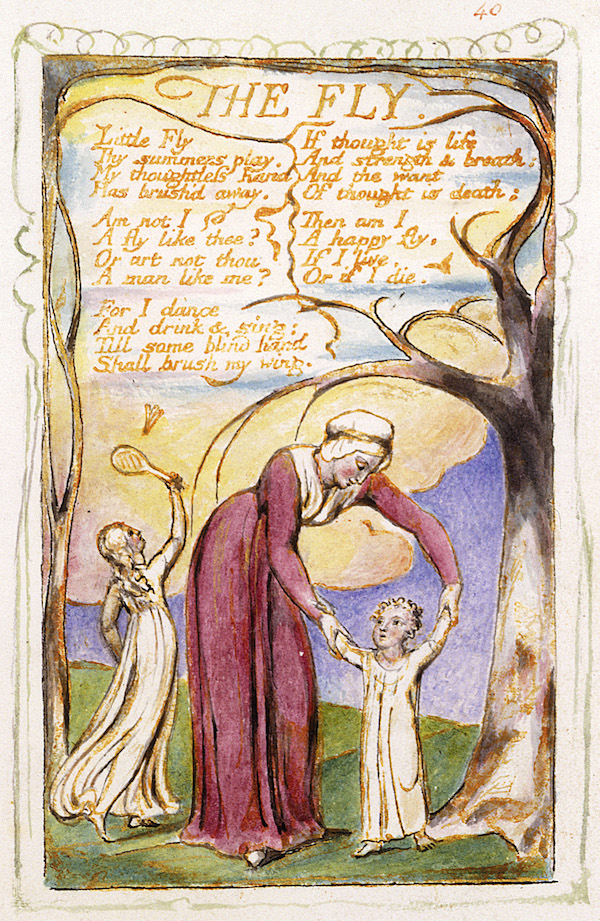

SY: Image is even more complicated with Blake, too, since there are visual illustrations that go along with his poems—“The Fly” being one with a particularly strange image. There’s this biography on William Blake, Eternity’s Sunrise by Leo Damrosch, who proposes that experience is taking place in the language, while innocence is taking place in the imagery surrounding it.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image courtesy of the William Blake Archive.

AM: I like that reading! Something that I noticed now, re-reading “The Fly” with you, is that the fly is happy. It’s thought-ful or thought-less, alive or dead, and it’s happy. The thoughts (inextricable perhaps from language?) come with experience; the idea that the want (desire for/lack) of thought is death comes from experience; and (not but) the affective condition of the fly is utter joy. This feels to me correct. The image of the scholar as morose is true to some extent, I’m sure, but I prefer the scholar-as-happy-fly. The image is all innocence; maybe it captures the naïveté of the thinker too, some rawness and curiosity. But then the image is given to us, in the poem, as language, and that takes experience. My other major association with flies in poetry is Emily Dickinson’s poem (“[I heard a Fly buzz—when I died—]”) where the fly buzzes at the window while the speaker is on her deathbed. The fly and the corpse are linked. Perhaps the fly enjoys some amount of decay, and maybe decay is the mark of lived experience in the world.

SY: Flies come up a lot in Blake’s work, and it is more popular to read images of the fly as a butterfly. This reading of it definitely brings in more symbolism—Greek mythology, the soul, etc.—but I’ve always preferred, in this poem in particular, to imagine it as a house fly, or a common fly, as it seems you do, too—especially as it begins Little Fly, / Thy summer’s play / My thoughtless hand / Has brushed away.

AM: I definitely get more out of the poem thinking about it as a fly, especially because of the mention of death.

SY: To circle back to your poem, “If Thought Is,” you end that poem with a riff on Blake’s stanza:

If thought is life

& the want

of thought is death

the incendiary dress

I’m curious if you could talk about how you arrived at that last line through the language of “The Fly” or the conceptual nature of Blake’s poem?

AM: I looked through my notes and drafts earlier today and discovered that “If Thought Is” was the first poem written for Some Beheadings, though I placed it at the end of the book. The early drafts had more of a summation at the end, more like “& the want / of thought is death.” But I was discovering with this first poem that certain kinds of summation were troublesome for me. Thought is ongoing and I wanted some sense that the thought could continue outside of the poem, or dissolve and become mysterious. Or so I assume, as I try to reconstruct what I was thinking. Eventually I came to three possible images: “the incendiary burns” (which is pointless), “the incendiary clothes,” and “the incendiary dress.” I chose “the incendiary dress.” It’s a way of ending on an image, the way Blake ends with happy fly floating around.

SY: Right, and I think what you’re saying is that you’re trying to end on something more open, something continual, instead of a dead thought, or a single thought. Which is interesting in Blake since he uses the logical sentence structure, “If this, then that,” which causes his poem to sound like it’s being concluded. Whereas in your poem you omit the “then” and end on an image-flash.

AM: Exactly. And it’s not always true that the dead poets have closure in their poems. It seems like closure, but really it’s more open. That’s another reason I like Emily Dickinson, because she’s quite experimental in her endings, which are often unsettling. And there is something unsettling about the ending of “The Fly”—one has to wrestle with this proposition of being happy whether you live or die.

S. Yarberry is a trans poet and writer. Their poetry has appeared in, or is forthcoming in, Indiana Review, The Offing, jubilat, Nat Brut, Cape Cod Poetry Review, FIVE:2:ONE’s #thesideshow, and miscellaneous zines. Their work will also be anthologized in Queer Voices: Prose, Poetry, and Pride, forthcoming from Minnesota Historical Society Press in May of 2019. Their other writings can be found in Bomb Magazine. S. is an MFA candidate in poetry at Washington University in St. Louis and the poetry editor of The Spectacle.

Aditi Machado is the author of Some Beheadings (Nightboat), which received the Believer Poetry Award in 2018, as well as several chapbooks, among which Prologue | Emporium (Garden-Door Press) is the most recent. She has translated Farid Tali’s Prosopopoeia into English (Action). Her writing also appears in Lana Turner, The Rumpus, Western Humanities Review, and other journals. Currently she guest edits FOLDER Magazine and works as the visiting poet-in-residence at Washington University in St. Louis.