The relationship between vivid, poetic language and visual art has always intrigued me. As an undergrad, I majored in studio art and English, and naturally see the two creative disciplines as more alike than they are different. Coming from this interdisciplinary perspective, I’m fascinated with Blake’s unique body of work but was surprised to find that, until the late 20th century, research on Blake was generally divided between art history and literary studies (“Plan of the Archive”).

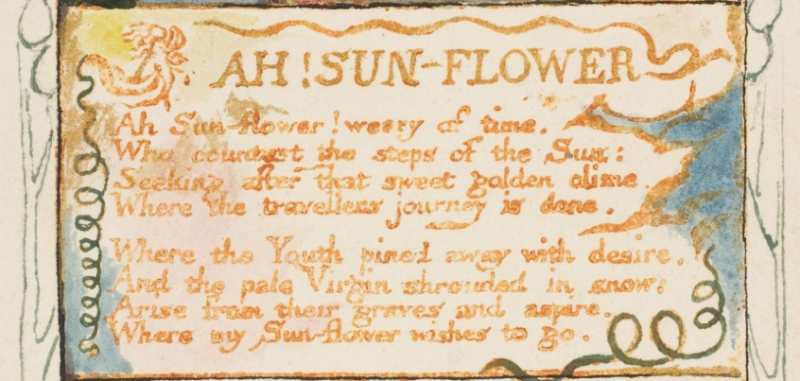

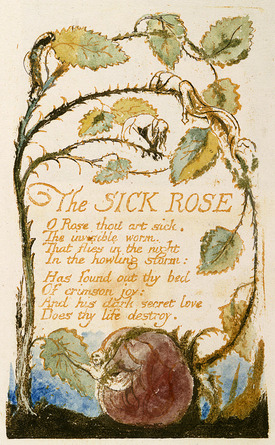

Furthering this divide is the fact that it’s expensive to print images in the anthological tomes English majors carry around, so many haven’t really seen his paintings. Conversely, art enthusiasts sometimes miss out on Blake as a wordsmith; I recently discovered that an artist friend of mine had no idea William Blake was even a poet. Though these relatively isolated approaches still affect the way new readers are introduced to Blake, the Archive has done much to present him as he probably saw himself–neither a writer nor a painter, but a unique blend of both. Blake seems to take full advantage of his creative space, utilizing his artistic skill to not just adorn his work but to heighten its sensory appeal.

The SICK ROSE Object 44 (Bentley 39, Erdman 39, Keynes 39)

He learned to draw early in life but began to write creatively at a young age, too. With the help of friends, his first collection of poetry was published when he was a young adult, just a few years after his engraving apprenticeship was completed (Bentley). Both talents were deeply rooted in Blake’s expressive abilities from the start, and the duality of his creative nature was as unusual as his artistic tastes. Throughout his education, he was inspired by Michelangelo, Durer, and other masters (“About Blake”). These preferences weren’t exactly vogue at the time, but despite being encouraged to study more popular artists, Blake was steadfast in his stylistic choices (“About Blake”). I can only admire his persuasion because it parallels my own training. While abstraction and highly conceptual art were popular styles, I took a more traditional path and studied 16th and 17th-century artists in hopes of developing my technical execution.

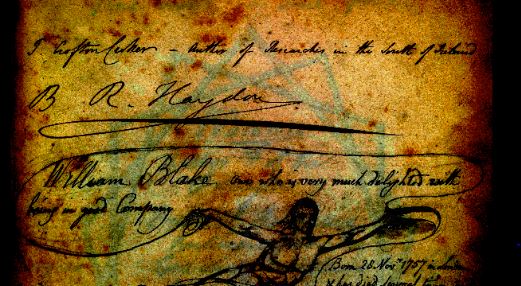

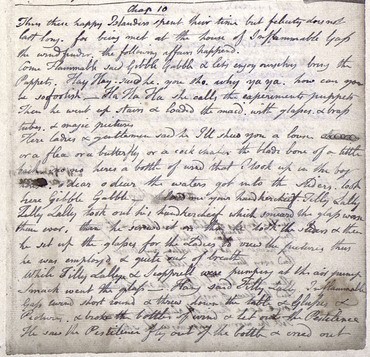

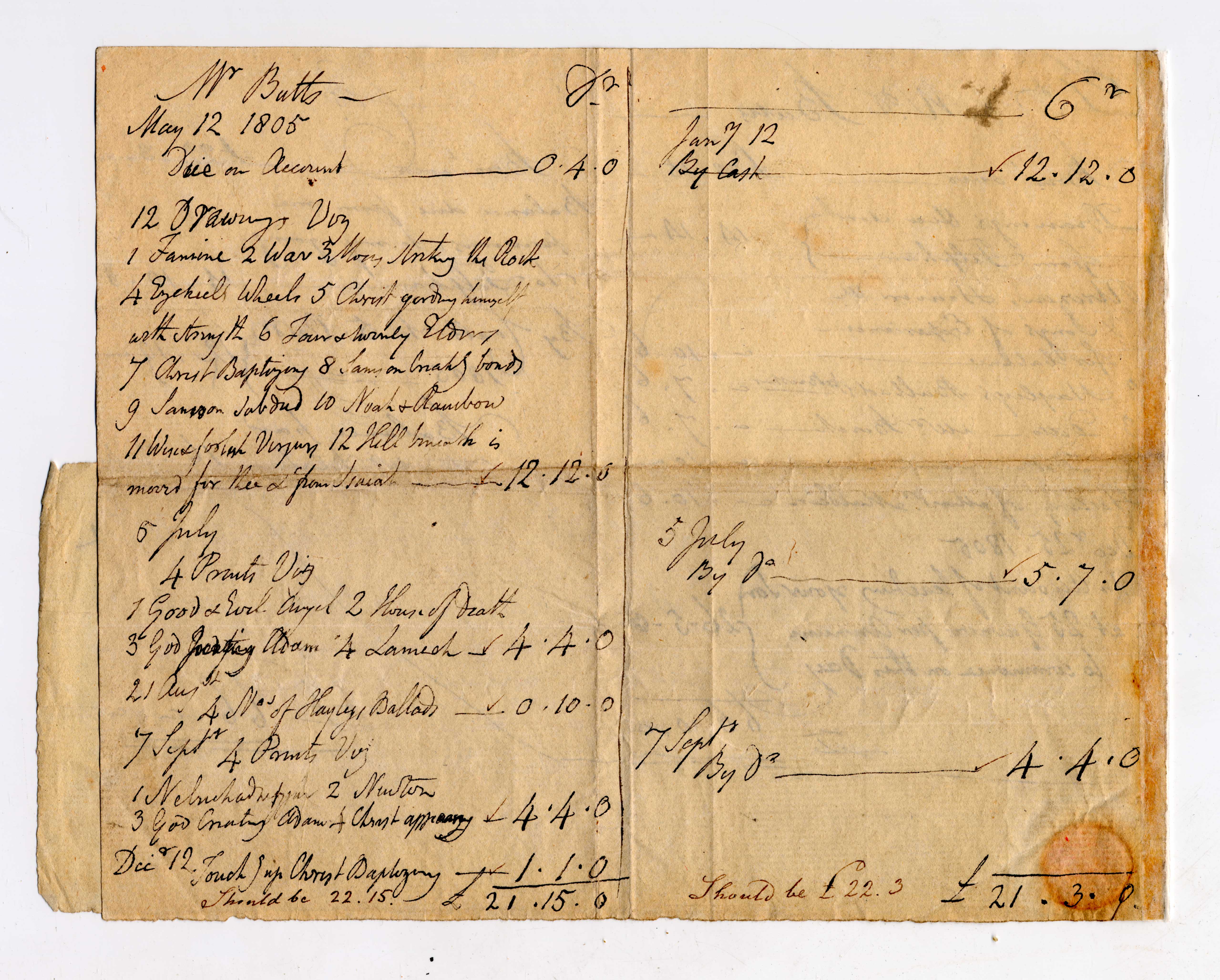

For example, when drawing something true to life, you have to forget that what you’re seeing is an object at all and pay attention to the breakdown of lines, shapes, textures and negative spaces–things your brain automatically synthesizes subconsciously. The visual process for analyzing manuscript images is virtually the same, and it’s a pretty useful perspective to have when proofing the receipts’ transcriptions. Like observing the details of a still-life subject for a sketch or painting, I’ve enjoyed testing the transcriptions by carefully comparing them to the receipt images. Our goal is to be as true to the original object as possible, so the little things really count. Especially when I come across an image that’s a bit more complex than the common 3-5 line receipt:

Looking at images like this, I usually ask myself: does the transcription represent the most accurate amount of spaces between words, dashes, and underscores? Are those dashes or underscores? Do the indentations in the transcription create alignment problems between lines? The irregular sizing of Blake’s handwriting, phrases wedged in between lines, and inconsistent gaps between words are a few of the things that make for interesting trial and error sessions on the testing site. The ever-enigmatic “ink drop or period?” dilemma occasionally arises. At the end of the day, the aim is to ensure that the visual integrity of what’s actually written is preserved after it’s rendered in the uniform font of a transcription.

Considering all the hard stuff is already done, receipt proofing has been a great way to practice the basics of XML. And with a little time and patience, it’s satisfying to finally find the right adjustments that allow a transcription to mirror the manuscript exactly as it should. So far, I’ve had a lot of fun putting my artistic skills to good use, particularly in the scholarly service of poet and artist, William Blake.

Works Cited

“About Blake.” The William Blake Archive, http://www.blakearchive.org/staticpage/biography. Accessed 25 November 2018.

“Plan of the Archive.” The William Blake Archive, http://www.blakearchive.org/staticpage/archiveataglance?p=planNEW. Accessed 25 November 2018.

Bentley, G.E. “William Blake: British Writer and Artist”. Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica Inc. https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Blake#ref211224. Accessed 27 November 2018.