It’s about time for Halloween for the Northern Division of the Blake Archive, and as the numerous Victorian houses of downtown Rochester begin to assume their position amidst the eerie late-October sky, a Blake enthusiast can’t help but wonder where the poet fit into all the ghostly proceedings.

Though the origins of Halloween aren’t clear, most scholars believe that the spooky holiday as we know it can be traced back to the Gaelic festival of Samhain. Samhain, observed from October 31st to November 2nd, marked the end of summer and the beginning of winter, so many of the festivities revolved around celebrating the harvest and beginning to make preparations for winter. However, there were often more than corporeal guests at the holiday table: spirits.

Due to the holiday celebrating the transition between a season of light and a season of darkness, the Gaelic believed that at this time, the world was at its most liminal, and as a result, spirits would be able to re-enter the physical world. In order to prepare for these wandering spirits, families would leave offerings of food to appease them or light bonfires to cleanse and protect their community from any lingering evil presences.

In the 8th century, Pope Gregory moved “All Saints Day” or “All Hallows Eve” (a holiday commemorating those who had died for their beliefs) from May 13th to November 1st, thus colliding directly with the pagan holiday (Moss). Some speculate this was the church’s attempt to Christianize the event, but regardless, the two festivals over time began to merge with one another. As a result, this is where we see the name of the holiday shift from “All Hallows Eve,” to “Hallow Eve,” to “Hallowe’en.”

The holiday saw a rise in popularity during the medieval to early modern period, and though it entered the mainstream, it still maintained many of its traditional Gaelic roots. For instance, bonfires were still widely used to ward off witchcraft or plague (the latter seemingly a nod to its harvest-focused origins), and carved vegetables, too, endeavored to scare off evil spirits with their spooky, illuminated faces. In the more modern traditions, a form of trick-or-treating arose where masked children pretended to be the visiting spirits and, after reciting some verses, would be “warded off” with treats.

In 1647 a number of autumnal holidays were banned by the newly formed parliamentary government, leaving Guy Fawkes Day as the primary fall festival (Moss). However, emigration to America (especially as spurred by the Great Potato Famine) forced voyagers to carry not only their families, but their traditions, across the pond. As a result, Halloween was initially treated as a charming “English” holiday, but it’s abundantly clear that the holiday has firmly rooted itself into American culture, seemingly unable to be scared away.

Now if something seems not quite right, it’s likely that you’ve noticed that the 1647 banning of Halloween and Blake’s time period (1757 – 1827) don’t quite line up. Regardless of the cancelation of the spirited holiday, the supernatural continued to thrive in English culture, and as we can tell through the biographies of Blake and the themes within his work— he didn’t completely shake the spooky spirit either.

Many of us have heard Blake referred to as a visionary, but until I joined the Blake Archive I didn’t realize the literalness of the description. Very early in his childhood, Blake began encountering “visions” not unlike those that we’d expect to see around Halloween. His first, appearing at the age of four, was God, who put his head to the window and “set [Blake] ascreamin'” (Bentley). Though most of them took the form of religious characters, such as angels in a tree (“About Blake”), abbeys suddenly filled with singing monks, or archangels that thoroughly enjoyed his works from heaven, not all of his encounters were benign.

“Did you ever see a ghost?” a friend once asked Blake. Despite regularly seeing what many of us would consider ghosts or apparitions, Blake responded that he had only seen one once. Standing one evening by the back door to his home in Lambeth, Blake happened to cast his eyes about the room and see a sinister figure which he described as “scaly, speckled, very awful” (Bentley 37) looming closer towards him. Terrified, Blake fled the house.

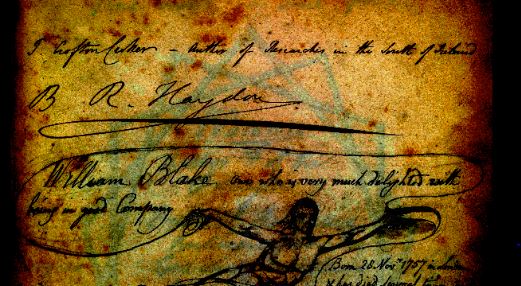

However terrified he might have been by that particular encounter, the supernatural continued to haunt both Blake and his work. In one of his more idiosyncratic pastimes, Blake and his friend John Varley would often hold nighttime séances in which the two would cast for figures of the past, and Blake would sketch them (Davis 146). Of these conjured specters, the most memorable figure is often considered to be the looming, bloodthirsty ghost of a flea. The corresponding painting, in all of its sinister and humanoid glory, is currently held in the Tate Collection.

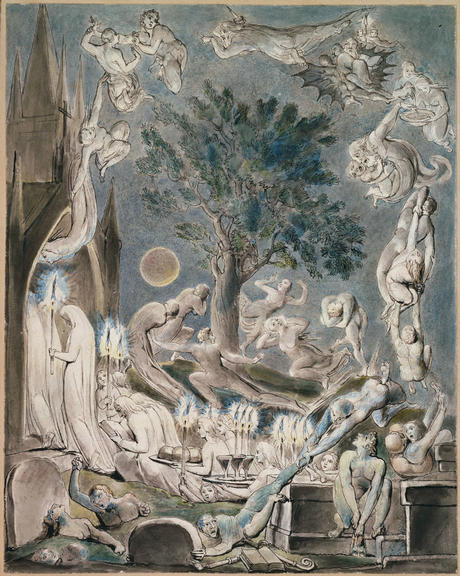

The Gambols of Ghosts, Object 3, 1805

Whether one regards The Ghost of a Flea or The Gambols of Ghosts, Blake’s haunting works often give their viewers a shudder and a hope that these apparitions remain locked within Blake’s imagination, rather than beginning their prowl amidst the physical world this Halloween.

Works Cited

“About Blake.” The William Blake Archive, http://www.blakearchive.org/staticpage/biography. Accessed 16 October 2018.

Bentley, G. E., editor. William Blake: A Critical Heritage. Routledge, 2002.

Blake, William. The Ghost of a Flea c.1819-20, in Nigel Llewellyn and Christine Riding (eds.), The Art of the Sublime, Tate Research Publication, January 2013, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/the-sublime/william-blake-the-ghost-of-a-flea-r1105542, accessed 17 October 2018.

Davis, Michael. William Blake: A New Kind of Man. University of California Press, 1977.

Millican, David. Untitled. 2017. Flickr, www.flickr.com/photos/98336874@N04/33292571440. Accessed 22 October 2018.

Moss, Candida. “Halloween: Witches, old rites and modern fun.” BBC, http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/0/24623370. Accessed 17 October 2018.