The William Blake Archive is pleased to announce the publication of a digital edition of Blake’s Notebook, based on fresh digital photography from the British Library and presented in Preview mode—with enlargements and basic bibliographical information but without transcriptions. Usually works in Preview mode lack illustration descriptions as well, but in this case the minutely detailed descriptions for each illustration in the Notebook are available and fully searchable.

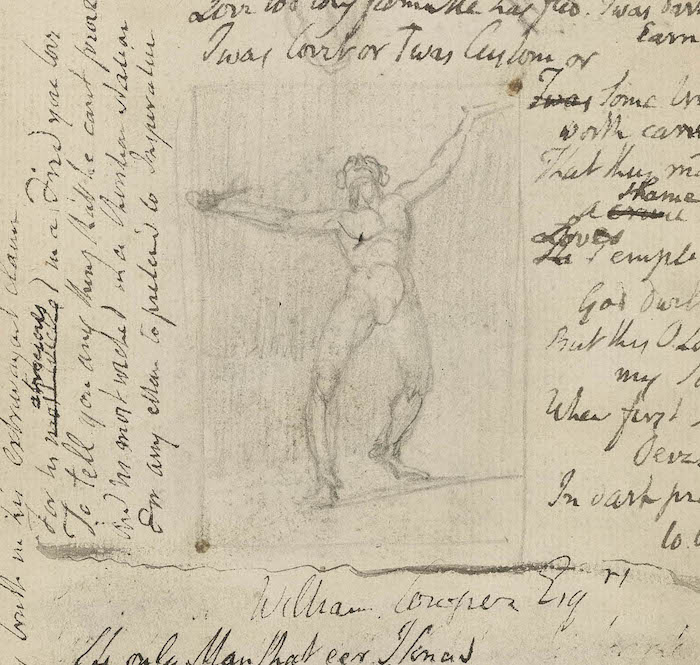

What we now think of as Blake’s Notebook was probably begun by his younger brother Robert for sketching and then preserved by William after Robert’s early death in 1787. Used sporadically, first for sketches—among many others, the early illuminated book Songs of Experience, the emblem book Gates of Paradise, and later Jerusalem—and then for more and more poems and prose, from A Vision of the Last Judgment to a projected Public Address on the history and state of engraving to miscellaneous memoranda on his craft—“To Wood cut on Pewter”—and his life—“Tuesday Jan ry . 20. 1807 between Two & Seven in the Evening—Despair” or, more upbeat, “23 May 1810 found the Word Golden.”

He filled the book from front to back and then turned it around and filled it from the other direction. He crammed its nooks and crannies. Then in 1818 he returned to the Notebook to draft the remarkable Everlasting Gospel in the few scattered spaces that remained—not quite enough, because he tacked on an extra fold of previously used paper for a bit more writing room.

We are fortunate that, shortly after her husband’s death, Blake’s wife Catherine seems to have passed the Notebook on to artist William Palmer (brother of better known artist and closer friend of William Blake, Samuel Palmer). Why William Palmer we don’t know, but that route bypassed Frederick Tatham, who inherited what was left of William Blake in Catherine’s hands at her death. In an outbreak of religious fervor that led Tatham to reject Blake’s infernal heresies, he eventually burned a considerable stash, contents mostly unknown. Safe from the flames, the Notebook went eventually from Palmer to Dante Gabriel Rossetti at a propitious time before Blake was slated for dramatic revival through the efforts of Alexander Gilchrist, his wife Anne, and their helpful associates and informants, including the Rossetti brothers, Dante and William. They were careful to minimize Blake’s objectional side as they shaped surviving materials. Dante Rossetti bound the Notebook with his own heavily edited transcription of “All that is of any worth in the book.”

The underlying pattern is familiar. Blake’s work became a well from which his sponsors withdrew the items “of any worth” for their project of rehabilitating Blake in a form suitable to advanced tastes of the third quarter of the nineteenth century—featuring an archetypal multimedia artistic genius with spiritual dimensions while downplaying elements that might feed the notion that their “Pictor Ignotus” was simply insane. It would take a new generation, led by E. J. Ellis and William Butler Yeats, in their lavish and extensive three-volume Works of William Blake, Poetic, Symbolic, and Critical, Edited with [296] Lithographs of the Illustrated “Prophetic Books,” and a Memoir and Interpretation (1893), to reach deeper into the well to retrieve stranger (and in most quarters less acceptable) writing and images as they constructed their unorthodox Blake with strong mystical inclinations.

Artists’ notebooks are often dissected and analyzed, of course, as part of the deep background for the genesis and evolution of texts and images. Editors of twentieth century printed editions almost always sorted items from the Notebook into meaningful literary categories—“Satiric Verses and Epigrams,” “Songs and Ballads,” “Miscellaneous Prose”—leaving little trace of the book as a whole—and of course omitting images altogether. But Blake’s Notebook, like its artistic kin, can and should also be considered as an integral work, in this case the work of a lifetime, unlike any other that he left us.

In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell Blake imagines a Printing House in Hell whose apocalyptic output—created by dragons, vipers, eagle-like men, and lions of flaming fire—”took the forms of books & were arranged in libraries” (Plate 15, Erdman page 40), there to await suitably apocalyptic readers to open the pages and liberate the volatile content. Artists’ notebooks, more than most books, declare their dynamic energies outright. Open the pages and you know instantly that you must participate. Blake’s Notebook, taken as a whole, as its own special kind of book, makes potent demands on its readers—and promises to connect us to an artistic life lived more than 200 years ago in ways that the preprocessed letterpress versions, indispensable as they are, simply cannot.

As always, the William Blake Archive is a free site, imposing no access restrictions and charging no subscription fees. The site is made possible by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with the University of Rochester, the continuing support of the Library of Congress, and the cooperation of the international array of libraries and museums that have generously given us permission to reproduce works from their collections in the Archive.

Morris Eaves, Robert N. Essick, and Joseph Viscomi, editors

Joseph Fletcher, managing editor, Michael Fox, assistant editor

The William Blake Archive