2018 marks the 100 year anniversary of the ending of WWI, (that is if you do not factor in the Treaty of Versailles in 1919) and just so happens to coincide with a graduate seminar I am currently enrolled in called “The Great War and Modern Memory.” This class has curiously overlapped in subtle ways with my time spent pondering Blake in the Archive. Blake, of course, did not fight in WWI, but in a strange mixture of past and present, similar to this blog post, he inspired many of the WWI poets and even artists who lived through the Great War and who drew upon his poetry and art in inspiring their own.

One of the most important ways Blake was utilized in WWI was through the poetry being written in the trenches. W.B. Yeats unequivocally voiced his derision of the artistic merits of this particular brand of poetry, famously opting not to include Wilfred Owen in his Oxford Book of English Verse (1936). Since then, the canon has been more kind, particularly to Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, Isaac Rosenberg, and Ivor Gurney. A recent (2013) Oxford World Classics edition edited by Tim Kendall has widened this canon to include other voices such as Mary Borden and Charlotte Mew to name just a few.

What, you may be asking, does all of this have to do with Blake? Well, Blake as has been previously pointed out, was an important Romantic influence, particularly on the work of Wilfred Owen. Owen’s poem “Futility” owes a passing resemblance to Blake’s “Tyger,” The last stanzas in the poem reading:

Think how it wakes the seeds-

Woke once the clays of a cold star

Are limbs, so dear achieved, are sides

Full-nerved, still warm, too hard to stir?

Was it for this the clay grew tall?

-O what made fatuous sunbeams toil

To break earth’s sleep at all? (Poetry First World War 169)

Blake’s now classic question in “The Tyger,” “what immortal hand or eye/ could frame thy fearful symmetry?” is repurposed in Owen as an inquiry as to “what” would create the “limbs, so dear” of a young soldier, only to have them die in battle. According to Tim Kendall, this repurposing of the Romantics shows Owen punishing “Romanticism by underscoring its indulgences and trumping its glorious illusions with the horror of modern warfare” (57).

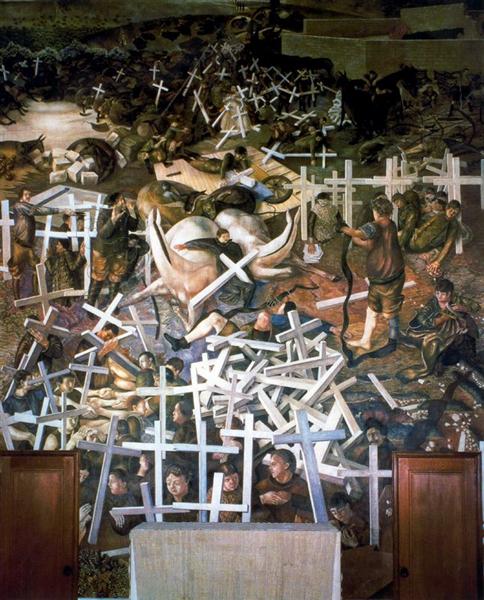

It was not, however, just the WWI poets who drew inspiration from Blake. As Jay Winter suggests in Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning, “the work of Blake was a frequent point of reference, through many canonical texts about the end of time as sources of inspiration and invective” (197). One artist in particular was Stanley Spencer who went to the Slade School of Art, had exhibited his artwork at Roger Fry’s exhibits in 1912 and 15, later joined The Royal Army Medical Corps (168). After the war Spencer continued to devote his life to painting and imbued his art with a combination of religious spiritualism and post-apocalyptic imagery. He was commissioned to create a series of images for the Burghclere War Memorial, The Resurrection of the Soldiers (1928-32, see below) being the most famous. The painting shows a mixture of Pre-Raphaelite realism mixed with a Blakean surreality. The canvas is littered with white crucifixes in a sea of troubled chaos, perhaps echoing the state of post-war Europe. Winter notes that “his was a spiritualism with marked similarities to that of Blake, albeit it on a less powerful and certainly less beautiful plane” (168). One of the things the painting does articulate is the interesting way that Blake continued to inspire artists and writers into the 20th century. On the centenary of WWI, it is fascinating to see the way Blake shaped the work and imagination of those who lived through the Great War.

THE RESURRECTION OF THE SOLDIERS