Recently, Oishani posted about the different choices scholars have made in their transcriptions of the “quirky” punctuation in Blake’s receipts. Currently, the protocol has been to attach a note to the specific line of the transcription in which these punctuation discrepancies occur. However, as Oishani points out, though Bentley and Keynes do not treat punctuation systematically, we still have many nearly identical notes about minute differences in punctuation. What is the importance in noting these differences? Should we focus on punctuation in the receipts on a larger scale? Oishani ends her post asking us to consider if it would be more useful to have individual notes on each of the receipts, or to have a set of notes that covers the entire set of receipts and discusses recurring issues like punctuation in detail?

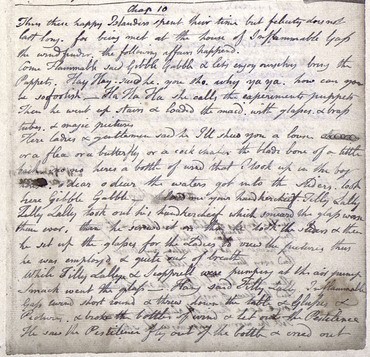

- Blake’s “quirky” punctuation

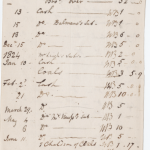

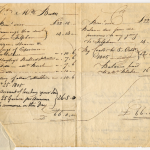

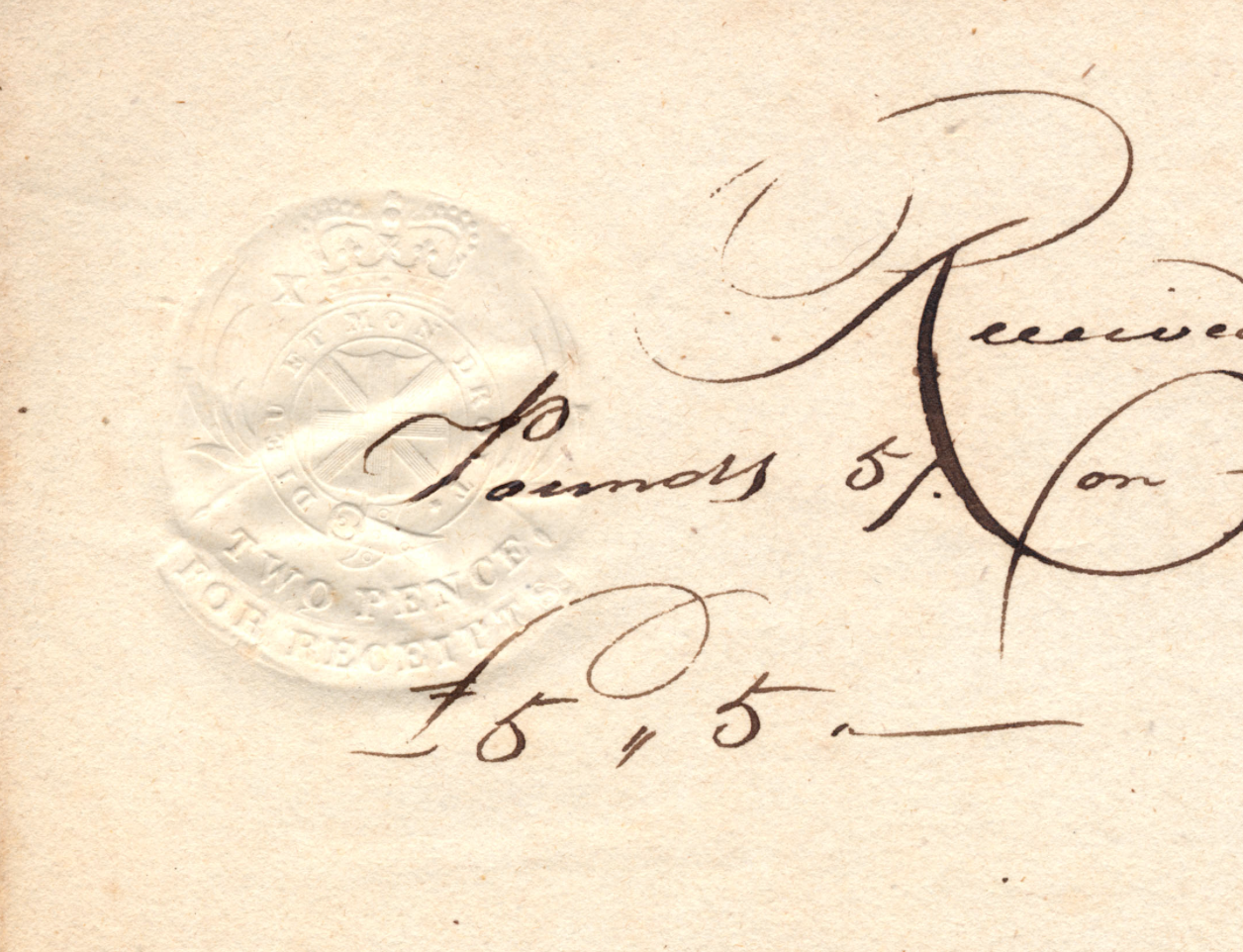

I began to think more seriously about this question not as I was finishing transcriptions and attaching notes to individual lines in the receipts, but as I was gathering provenance information for the receipts. How should I organize the notes in this section? What have we done for other, already published, works in the Archive? For example, we have been putting the embossed stamp information in the “Object Note” section, but would it better fit for another category—as a subset of the “Copy Information” section perhaps? I realized that while Bentley and Keynes may have dealt with Blake in a less than systematic way, our project should strive to be as standardized as possible. Notes are a useful aspect for the Archive because they allow us to discuss various features of Blake’s work and also provide additional sources of scholarly information. But, I think, when creating notes, the most important thing to keep in mind is the audience.

Embossed revenue stamp for October 15, 1806. Where should we include notes about this feature?

The most challenging (and rewarding) element of editing for the Archive is that we have so many potential audience groups to consider. The Blake Archive is used as an educational tool for students of all ages, across numerous fields. It is also a useful resource for more serious Blake scholars. And, as a public website, it can be accessed by anyone looking to learn a little more about Blake, engraving, or Romanticism (to name just a few things). How do we relay the information important for our various audiences? And how do we introduce specific, appropriate information to our audiences in a manner that can provide them with what they might not necessarily be looking for, but might find interesting and useful? Returning to the example of the embossed stamps, we must consider which of our audience members are interested in embossed stamps and what other aspects of the work they might be interested in—how can we organize the notes of the receipts to be useful for everyone who might read this section of the Archive?

The notes we choose to include and how we lay out these notes demonstrate, above all, our awareness of audience. When dealing with Blake’s punctuation, it might be useful to include a general note about the importance of punctuation variation and the way it varies among different scholars. Perhaps we can format and use the “Group Information” tab for these notes or even include some of this information under the receipts “blurb” in the Archive. Other, more specific notes detailing Bentley and Keynes’s scholarly discrepancies might fit well under the “Work Information” or “Copy Information” sections.

Notes can also be used to explain differences in our transcription from the object. These differences are mostly due to the limitations imposed on us by our software. That said, how do we transcribe, much less make notes on receipts like these?

The receipt project, though seemingly simple, allows us to consider our audience in a new way. It is important to use notes as a tool to explain both our own editorial decisions and those of past scholars;however, notes become the most useful and relevant when we remember to keep our audience in mind.