The William Blake Archive recently published seventeen pen and ink drawings by Blake that span the majority of his artistic career. As one of the art historians on staff at the WBA, I was tasked with the responsibility of creating XML documents to accompany each of the works—files that we call Blake Archive Documents or BADs. These BADs are incredibly important as they include not only textual descriptions of the drawings but also tagged search terms, which enable the new drawings to be plugged into the existing search function of the WBA.

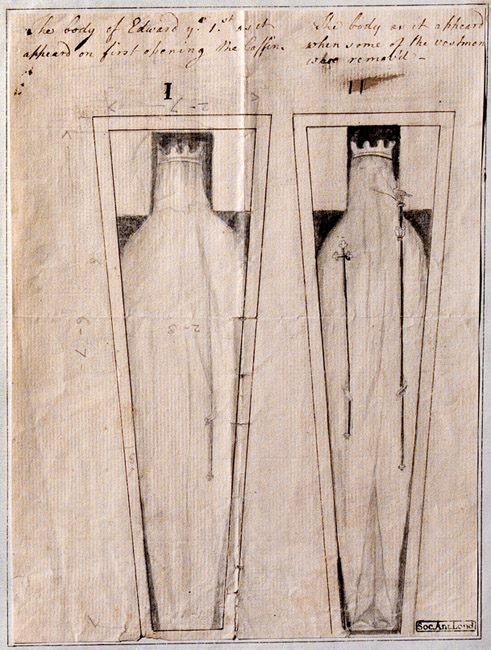

For example, if a visitor to the WBA is interested in finding all of Blake’s works that illustrate kings, he or she could search the term “king,” and the resulting list would now include two of the newly published pen and ink drawings as they too were tagged with the term “king”: “The Body of Edward I in his Coffin, Two Rough Drawings” and “Saul and David: ‘And Saul Said Unto David, Go, and the Lord Be With Thee.”

We call this process of describing and adding tagged search terms to individual works “markup.” The WBA maintains a comprehensive list of search terms from which all project assistants marking up works draw their vocabulary. Terms on the list include figural types, specific names, objects, structures, types of vegetation and gestures, actions, and many others. My personal favorite is undoubtedly “streams of gore,” which actually produces eighteen hits when searched! As additional works enter the WBA, we continue to add new terms to this list with the ambition to represent as closely as possible the range of material available to be searched and explored.

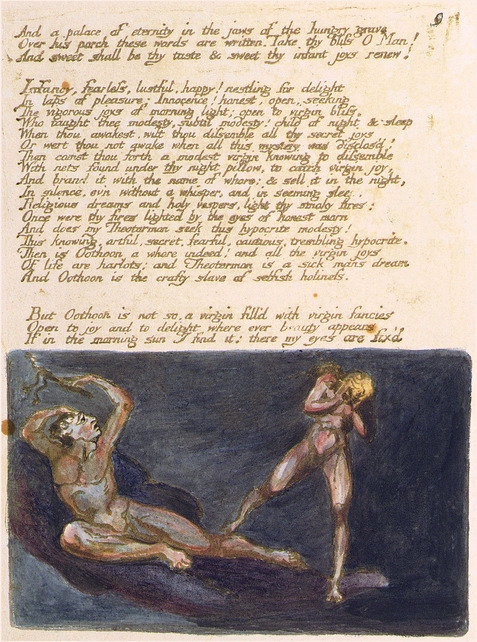

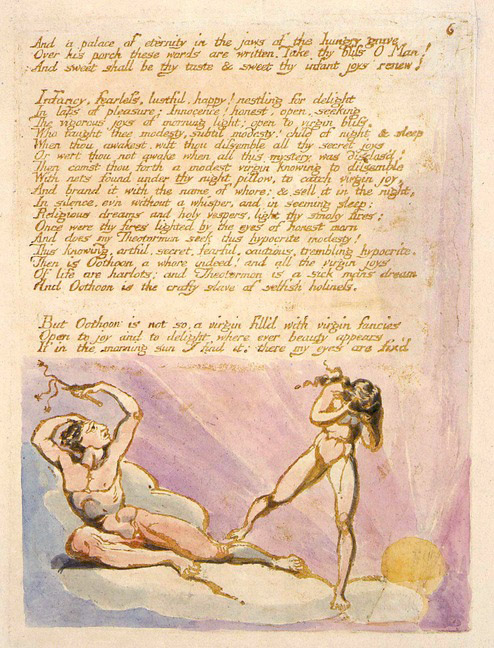

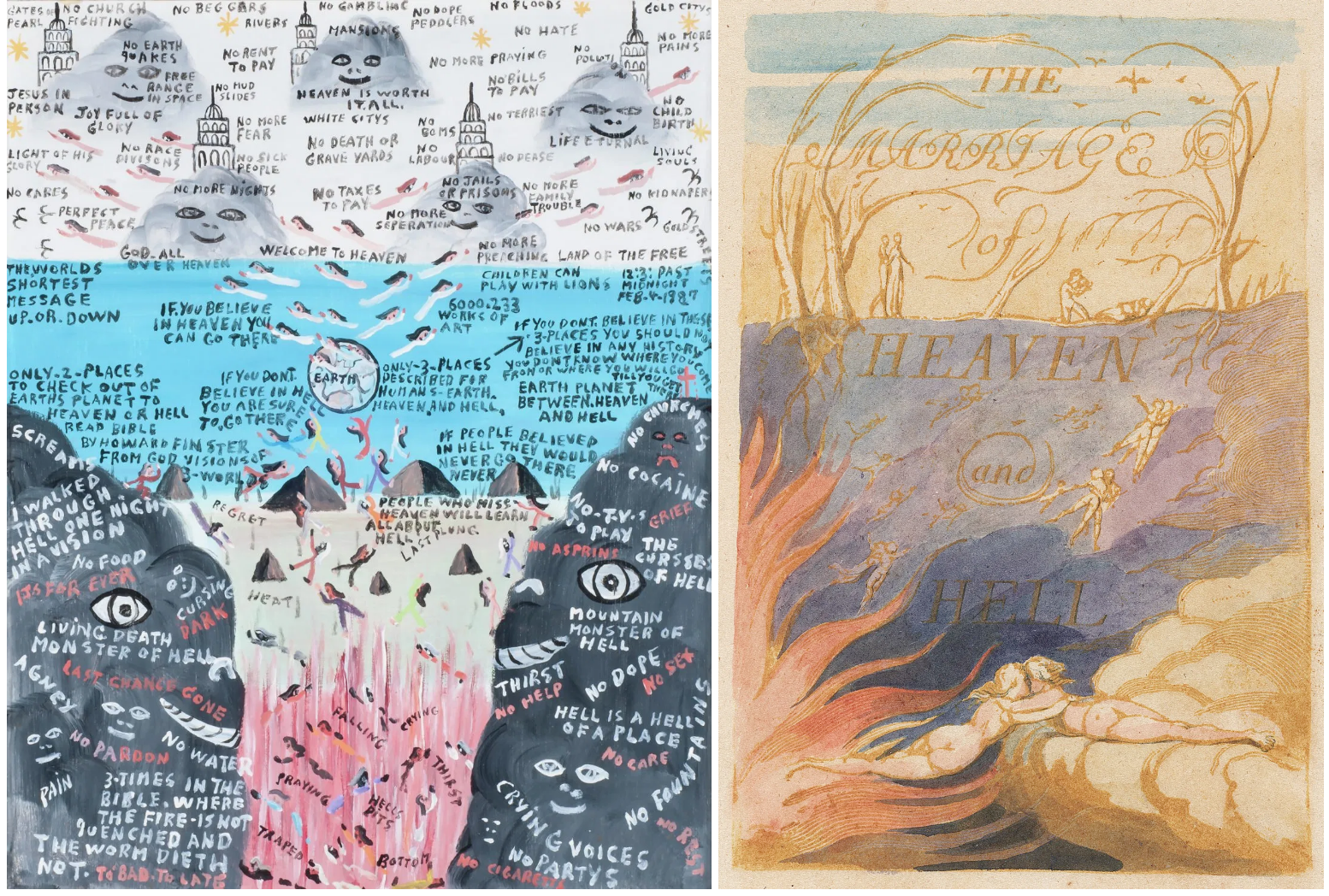

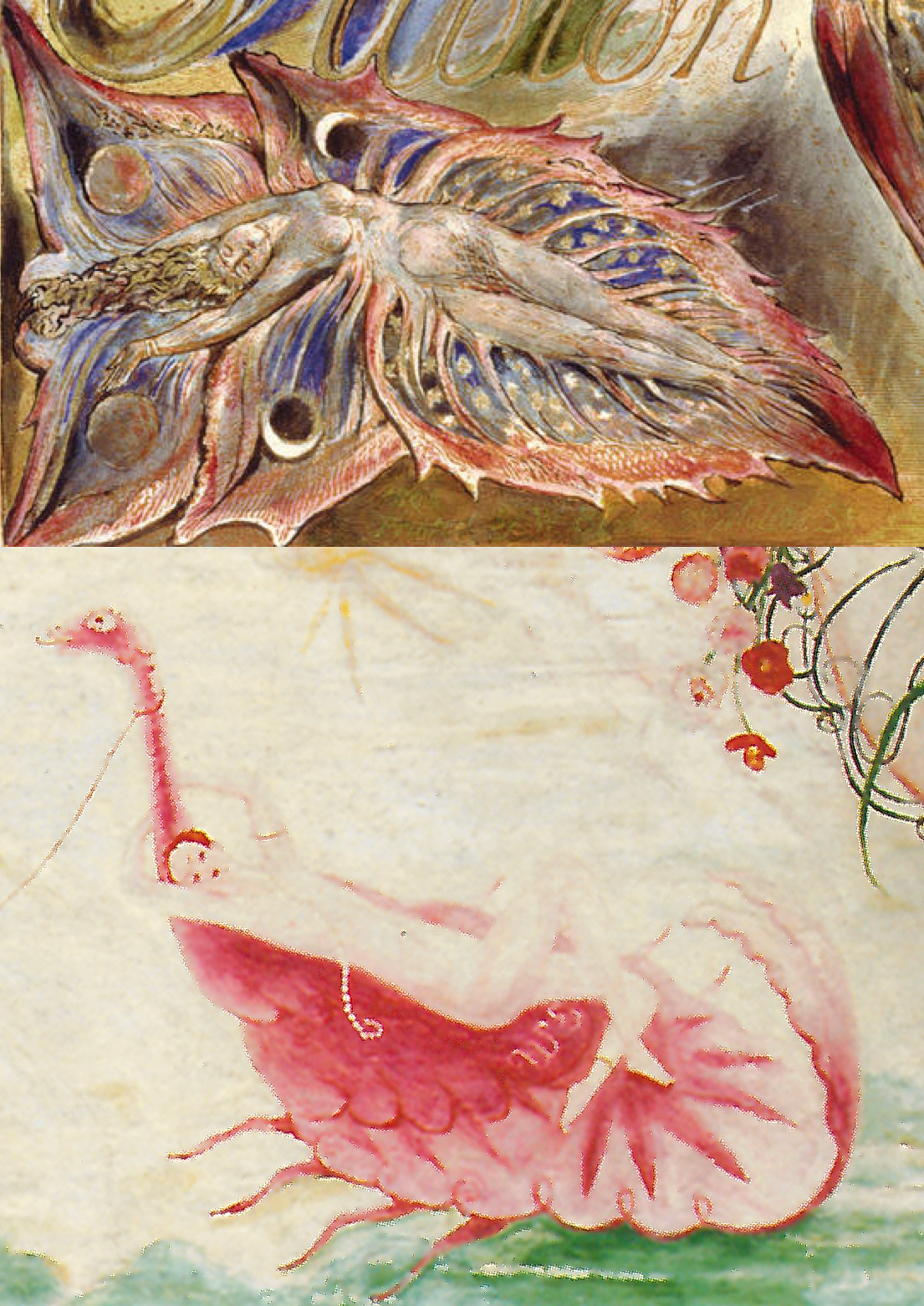

Sometimes this process of adding terms to objects is relatively straightforward. For example, the WBA may acquire the images of a particular copy of one of Blake’s illuminated books, such as Visions of the Daughters of Albion. When creating the BAD for this object, we would use the existing BAD of another copy of the work as a template—or “copy text”—for the new copy and only make changes according to variations particular to the newly received copy. For instance, we might add the search term “night” for copy G of Visions from 1795 while including “sunrise” or “sunset” for copy C from 1793.

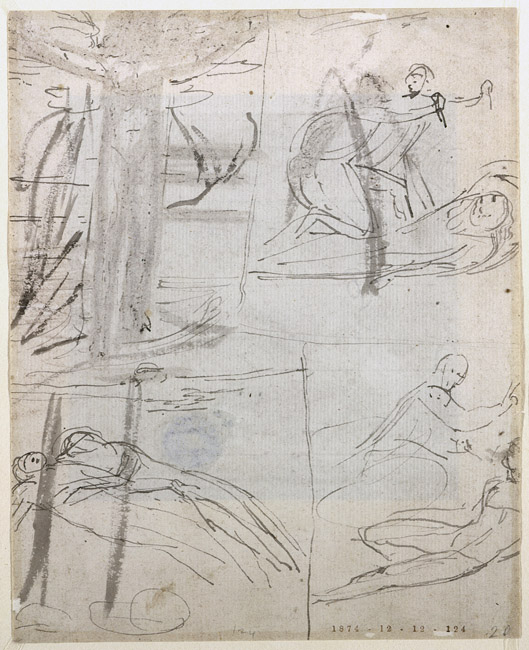

When marking up pen and ink drawings, however, this process becomes much more complicated, in no small part because you encounter many forms or marks that are difficult to make out—to figure out what the marks represent—but mostly because there are no templates for unique objects. We call this type of markup “working without a net.” Although Blake’s illuminated books are certainly all unique objects, grappling with graphic media is more difficult, in my opinion, because there is not even a common plate or source from which the works were derived. Thus when faced with a drawing such as “Four Composition Sketches,” seen below, it is often difficult to even pinpoint a place to begin translating image to text since the forms themselves are sketchy, often fragmentary, and very faint. I find myself turning to other staff in the WBA office and asking questions like, “does this look more like a rock or a severed head to you?”

Thankfully for me (and everyone who uses the WBA), the markup process is by no means singularly subjective. Martin Butlin’s nearly comprehensive catalog of Blake’s paintings and drawings from 1981 remains a crucial resource for image markup. I also collaborate closely with WBA senior editor Robert Essick, always relying on his expertise to confirm (or revise) readings suggested by both Butlin and myself. After creating a BAD, I send it to Essick along with a supplementary document explaining certain choices, asking questions, and hoping frequently for a new perspective. This process often leads to an e-mail exchange that may persist over several days as we piece together the best possible description and tags for each new work entering the WBA.

Thus, like most aspects of the WBA, markup is a collective effort that involves many people grappling not only with Blake’s particular way of rendering form and narrative but also the difficult issue of condensing such visual variety into often single-word text tags. At the same time, however, perhaps the most challenging aspect of dealing with Blake, always with one foot in the image and one in the text, is also the most exciting, particularly because of the greater accessibility these pen and ink works now enjoy on the internet as part of the WBA.