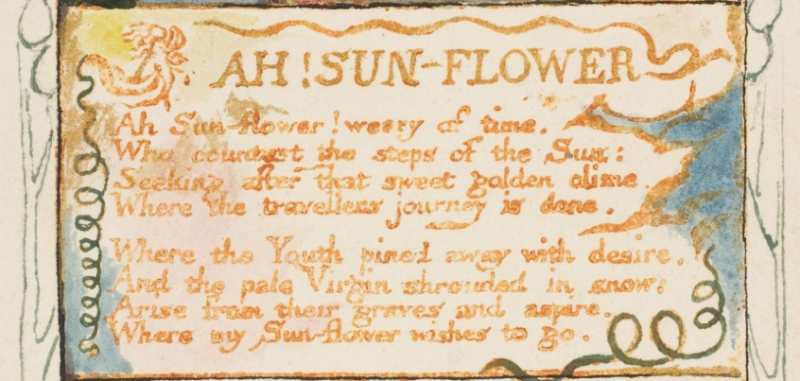

Since re-grouping in January, the members of BAND have been working earnestly on a variety of new and ongoing projects, including Blake’s Descriptive Catalogue, Receipts, The French Revolution, Chaucer, Prospectus, The Four Zoas, Genesis, Tiriel, and additional groups of Blake’s letters. In an effort to do more shameless plugging for our imminent letters publication, I’d like to share why I decided to continue with the letters project.

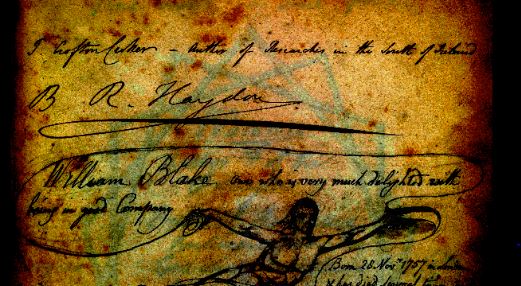

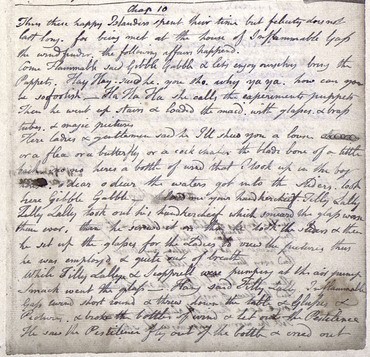

On a more practical note, I wanted more experience in building XML files from the screen-up and in gathering provenance info for problematic or untraced letters. Yet there’s another reason I couldn’t stay away from the correspondence of Will Blake. As a Romanticist who has read and studied Blake’s poetry, I find that it is sometimes easy to forget that beyond Blake’s artistry, beyond his philosophical and mystical Ideas, there existed an actual human being. After working on one of Blake’s letters last semester, I realized that we often think of Blake the Poet, or Blake the Engraver, but not Blake the man—someone who lived, breathed, socialized, gossiped, fell ill, worried about money and work, conducted business with a host of acquaintances, expressed opinions, and often let his imagination wander into the realm of the visionary.

As my fellow members have mentioned in previous posts, Blake’s letters are indeed a microcosm to the editorial process and an important means of contextualizing Blake’s body of work, as well as his network of acquaintances. I would also add that the letters, by virtue of their brevity and personal nature, compel us to ask the following questions:

What is the relationship of digital editing to the individuality of the writer?

How does metadata allow us to enhance and expand our understanding of the writer’s life and work?

As digital editors who deal with Blake’s handwriting, manuscripts, and typographical works, we often find that individual letters—as symbols used to represent speech-sound—are spaces of interpretation. No matter what medium we may encounter them in, our task as editors is to figure out how to visually represent these letters and encode meaning using the technological tools at our disposal. And Blake’s letters, both as symbols and as written messages addressed to others, reveal not only the mundane and transcendent aspects of his day-to-day life, but also remind us of the stuff that makes up our own daily lives.

So I say: onward to the letters. (Besides, where else can you read about Blake being on a good train, his Work in Abundance, and the sound of harps before the Sun’s rising all in one convenient package?)

—