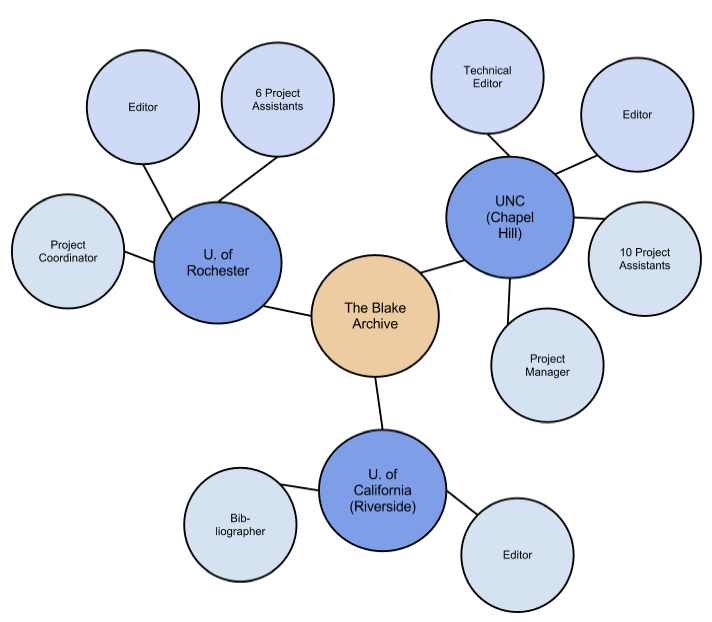

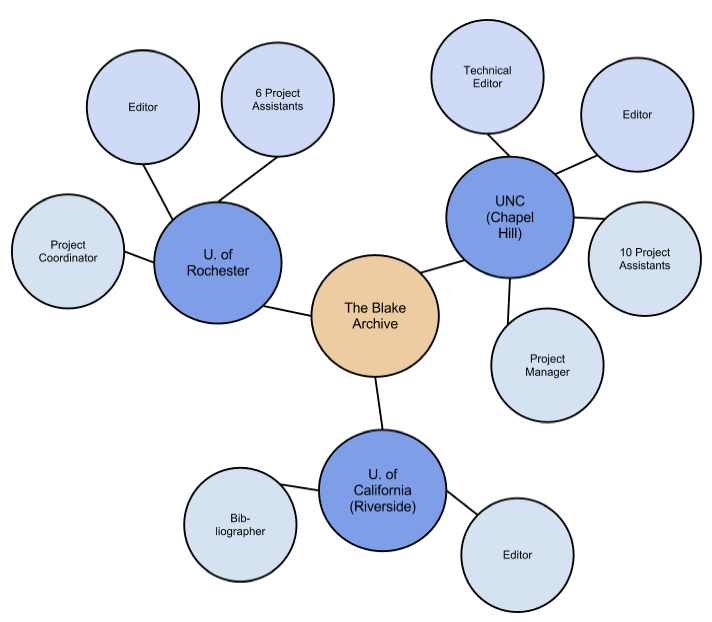

The Blake Archive has people all over the place. Three editors at three different institutions in three different states, two “teams” of project assistants/graduate students, a Technical Editor (grad student), Project Manager (grad student), and Project Coordinator (grad student—that’s me!).

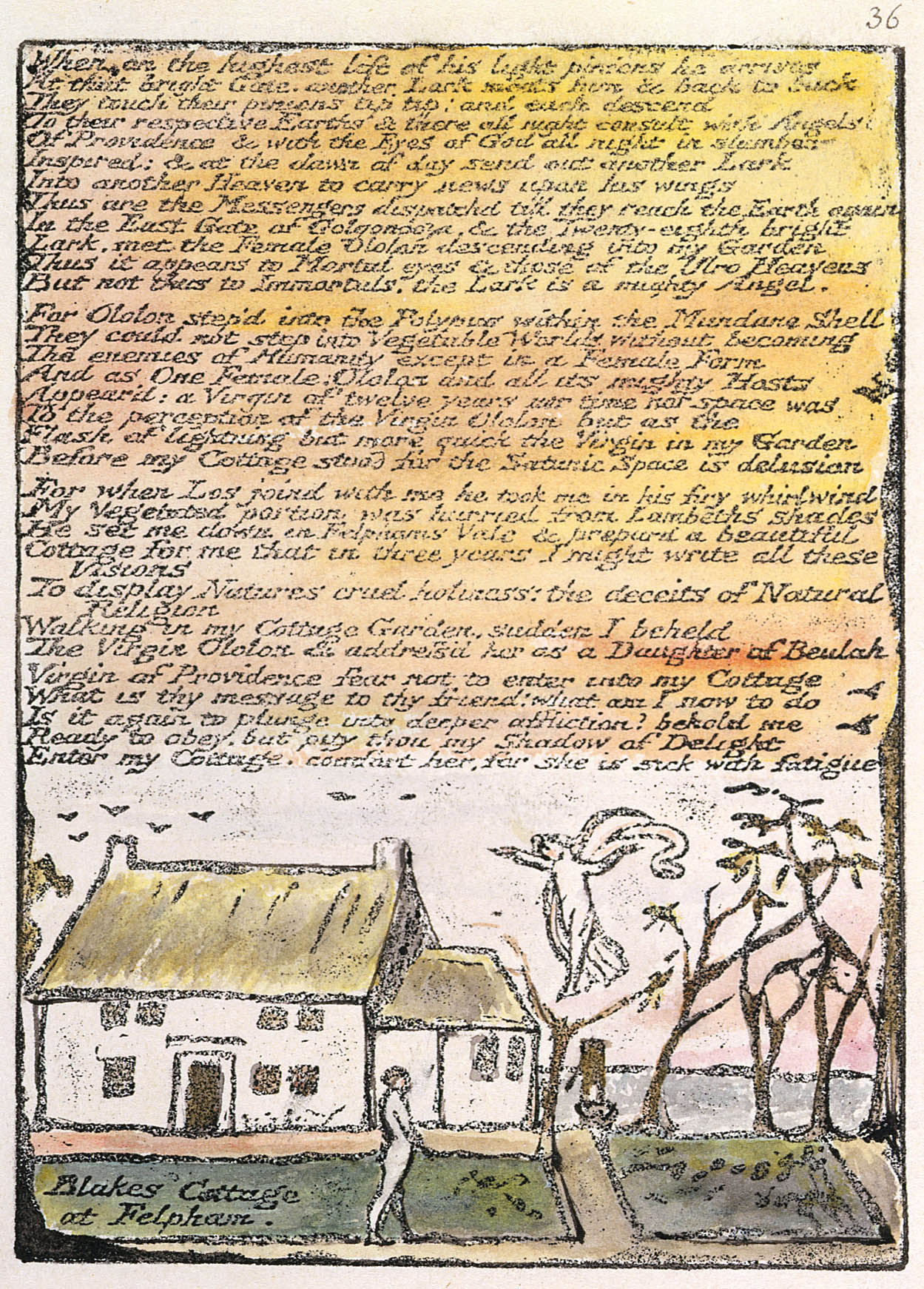

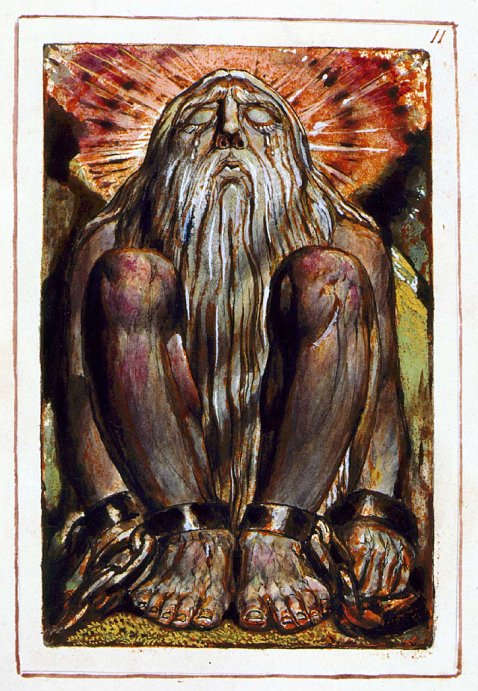

The domain of Team Rochester (or more informally, BAND: Blake Archive Northern Division) is Blake’s manuscripts and (more recently) typographic editions. Our first publication was Island in the Moon and we’re currently working on electronic editions of Blake’s letters, the Genesis Manuscript, Poetical Sketches, and Four Zoas. Typically, teams of project assistants work together on a single text or group of texts (as in the case of the letters), but sometimes individuals work alone on “easy” manuscripts (which is really a misnomer for anything of Blake’s).

As the job title (Project Coordinator) implies, my job is to coordinate projects. This means several different things, but mainly I keep track of who’s working on what at the UR and I coordinate BAND’s activities with the Project Manager, Ashley, at UNC. The digital heart of the Blake Archive—its servers—is at UNC. Which means that the work we do at the UR involves complicated procedures to log in securely from far away. BAND is also the newest “wing” to the Blake Archive. Combine a bunch of people relatively new to the Blake Archive and the world of electronic textual editing with the labyrinthine world of servers, “tunnels,” and “run this command in the terminal window” [“What’s a terminal window??!”] and you can see the need for some coordination.

As the job title (Project Coordinator) implies, my job is to coordinate projects. This means several different things, but mainly I keep track of who’s working on what at the UR and I coordinate BAND’s activities with the Project Manager, Ashley, at UNC. The digital heart of the Blake Archive—its servers—is at UNC. Which means that the work we do at the UR involves complicated procedures to log in securely from far away. BAND is also the newest “wing” to the Blake Archive. Combine a bunch of people relatively new to the Blake Archive and the world of electronic textual editing with the labyrinthine world of servers, “tunnels,” and “run this command in the terminal window” [“What’s a terminal window??!”] and you can see the need for some coordination.

At the UR, I keep track of who is working on what and how they’re doing. This is primarily accomplished through our weekly staff meetings, for which I set agendas (and during which another project assistant takes minutes). These get posted to BAND’s Google Site, which we use to keep track of things like meeting minutes, technical documentation (for example, the XML tagset for transcribing manuscripts), project documentation (such as proofreading questions), and the links we use frequently. We had been using Blackboard for a while, but we recently migrated to a Google Site, and that seems to work really well for us.

One of the advantages of using a Google Site is that it plays well with Google Docs, which we use extensively. All of our project tracking and proofreading takes place in and through shared Google Docs. As team members begin transcribing and encoding Blake’s text into XML, questions tend to arise. At that point, someone will start a Google Doc for that project, record their questions, and then share it with the rest of BAND. Some of the easier questions (such as “Do we transcribe the handwriting of librarians or archivists?” (Answer: no)) will be answered via the comment feature, or in differently formatted text. Trickier questions (by far the more common species) we address during our weekly meetings, and occasionally escalate to the Blake Archive’s listserv, which gives non-UR folks (typically the other editors, the Project Manager, and/or the Technical Editor) a chance to weigh in.

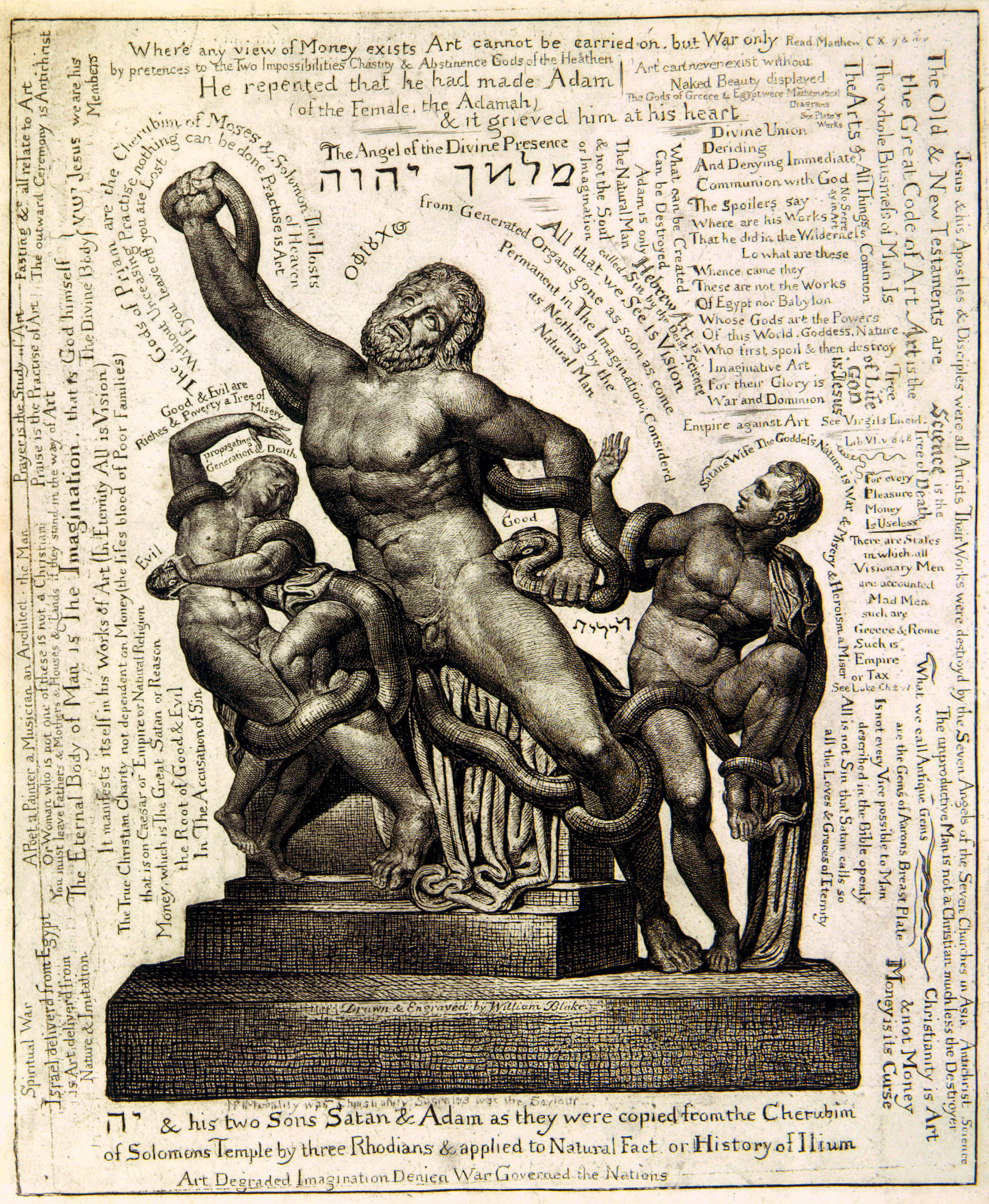

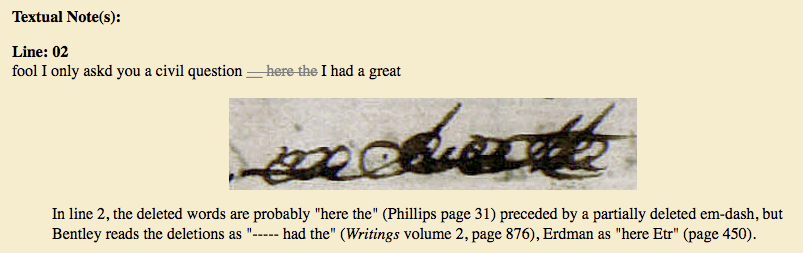

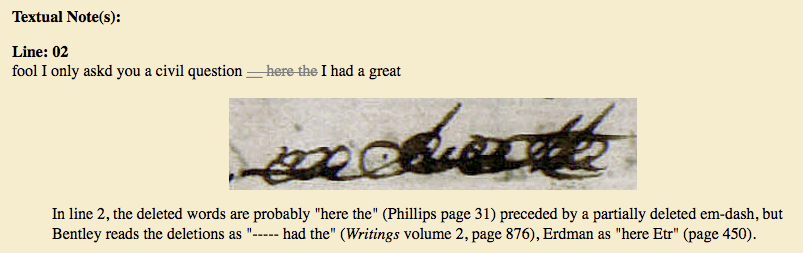

Once a MS has been transcribed and encoded, it’s ready to be proofed. Once again, we record errors (such as typos) and questions (“Is that a comma or a period?”) in a Google Doc. BAND spends a lot of time scrutinizing small details and discussing at length whether or how to record/transcribe/encode something. In a few seconds and with just a few clicks, project assistants can neatly snip a close-up of whatever mark, letter, word, or line they have a question about and insert that into the proofreading document. Having images right next to specific interpretive questions makes our detailed discussions (which have been known to induce brain-death and existential confusion) about things like dashes much easier to manage. In fact, our reliance on these kinds of images contributed to one of the new features in the Archive, which debuted with Island in the Moon: text-note images in the editorial notes to help explain particularly knotty editorial cruxes. Here’s an example from Object 2 of Island in the Moon:

One last word about managing the work of proofreading. We just started using a Google Survey to make proofing more consistent. Nick Wasmoen, one of the project assistants at the UR, built a proofreading form in Googledocs, which we now use for all of our proofreading. It details everything a proofer needs to check, from typos in the title to errors in copy information or the transcription. Using the document maintains consistency in proofing across texts—this is especially important as we all proofread each other’s work, and this ensures that we all look at and for the same things.

Another aspect of my work at the Blake Archive is being the link between BAND and the folks at UNC—especially the Blake Archive Project Manager, Ashley. When BAND members run into problems I can’t solve (such as log-in issues on the server) or questions I can’t answer, I talk to Ashley. We have regular video chats, during which we share updates about project progress and I get to ask lots and lots of questions about how and why the Archive works the way it does. We’re using Google Video Chat, which seems to work well a majority of the time. We occasionally have issues where one of us can neither be seen nor heard, but it usually works.

Sometimes I’m conflicted about relying so much on Google for tracking and managing our collaborative editing projects. But it’s just so easy! And free! And right there! And easy! And when you spend hours scrutinizing ink splotches or determining whether that “s” is *really* capitalized, “easy” works.

Continue reading