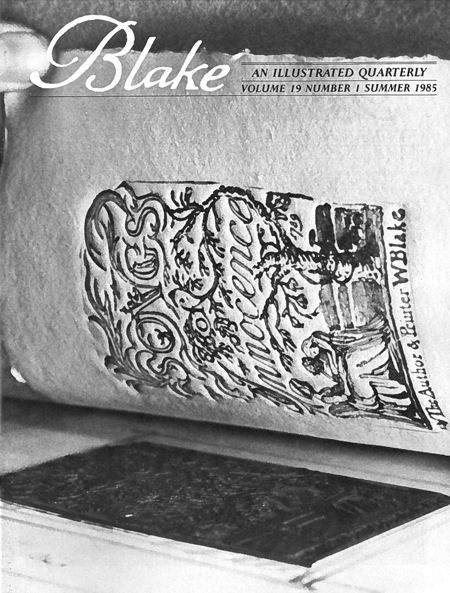

For my most recent task as one of the project assistants digitizing Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly, I had to resize and rotate images from the journal that are blurry, crooked, or otherwise aesthetically displeasing. This task is about as complex as it sounds. I enter width values into XML documents or slightly rotate files, finessing how the pictures appear on the page until I am satisfied with the result. The images that require attention are not the materials from the William Blake Archive, which appear as high quality scans in the articles with links to objects in the archive, but instead are images the archive does not have, either because they are not Blake’s work or they are unavailable, and so have been cropped from PDFs made from scans of the printed editions that include grey-scale photos of the originals. Which, as that convoluted sentence suggests, means these cropped PDF images are fairly removed from their origins. And as a nascent book historian fascinated by materiality, in relation to both print and digital editions, I am reminded of the significant consequences of editorial choices even when they are as minor as adjusting how images appear on a page. Along with the other graduate students completing this project, I am leaving fingerprints of yet another mutation on the material.

Bibliographers and digital humanists have an ongoing debate about the effects of transmission and reproduction, especially in relation to technological advances. Thomas Tanselle, writing in 1989 before the digital boom, argued that “every reproduction is a new document.”[1] Albeit he was considering reproductions in terms of Xeroxes as replacements for original materials, but as scholars like Matthew Kirschenbaum and Bonnie Mak have persuasively argued, the materiality of digital objects also necessitates each reproduction to be considered unique, believing like Tanselle that “with characteristics of its own […] no artifact can be a substitute for another artifact.”[2] Each modification leaves traces behind. For Mak, a palimpsest serves as a useful metaphor to comprehend this layering of meaning through mediation since “Palimpsests, by definition, are evidence of an effacement that is incomplete; they transmit vestiges of their former lives […] [and] digitizations may be recognized as vibrant and historically situated sources in their own right that offer alternative points of entry into enduring debates about the production and transmission of knowledge.”[3]

According to these definitions, even the minute changes in size, which are mostly arbitrary and based on aesthetics, add another layer of meaning that both changes the object and affects readers’ experiences of it. This dilemma is nothing new—it’s one that has been raised by the editors from the project’s beginnings—and it reveals the issue of theory versus practice. In theory, each action made by editors and project assistants alters the material. But in practice these many of these changes occur below the threshold of human vision. There are alterations that meaningful and discernable, and there are ones that are not.

Of course the adjustments I make on these images are not to efface the original, but rather to better represent the articles in a different medium. The main goal is to improve the appearance of image quality. By shrinking the scans, grainy pictures become sharper. My tinkering is well-intentioned and never purposefully distorting, instead done with an eye to clarify what appears blurry. But these modifications do have consequences, perhaps inescapable in the transition from print to digital. For instance, the size difference online prioritizes the images from the Blake Archive, and rightfully so in a journal that emphasizes Blake’s illustrations. To look more closely at the cropped scans requires more engagement by the reader, who must click on the image if they want to see a larger version, or open the link to the full PDF of the issue (though again, they will download a reproduction). So I can’t help but wonder about the effects of medium on interactions with the journal, and what is enabled and lost in the process of editing it, even when making the smallest of changes. As to how meaning changes with difference in image size, however, is up for readers to decide.

[1] Thomas Tanselle, “Reproductions and Scholarship,” in Literature and Artifacts (Charlottesville: Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia, 1998), 70.

[2] Ibid., 70.

[3] Bonnie Mak, “Archaeology of a Digitization,” JAIST 65.8 (2014): 1516.

Continue reading