Blake Exhibit: Petit Palais (Paris)

Michael Phillips will be curating the first retrospective of Blake’s work in France at the Petit Palais April 2 – June 28, 2009. View the press release here.

Continue readingCategory

Michael Phillips will be curating the first retrospective of Blake’s work in France at the Petit Palais April 2 – June 28, 2009. View the press release here.

Continue readingThe William Blake Archive is pleased to announce the publication of the electronic edition of Milton a Poem Copy B. There are only four copies of Milton, Blake’s most personal epic. Copy B, from the Huntington Library and Art Gallery, joins Copy A, from the British Museum, and Copy C, from the New York Public Library, previously published in the Archive. Blake etched forty-five plates for Milton in relief, with some full-page designs in white-line etching, between c. 1804 (the date on the title page) and c. 1810. Six additional plates (a-f) were probably etched in subsequent years up to 1818. No copy contains all fifty-one plates. The prose “Preface” (plate 2) appears only in Copies A and B. Plates a-e appear only in Copies C and D, plate f only in Copy D. The first printing, late in 1810 or early in 1811, produced Copies A-C, printed in black ink and finished in water colors. Blake retained Copy C and added new plates and rearranged others at least twice; Copy C was not finished until c. 1821. Copy D was printed in 1818 in orange ink and elaborately colored. The Archive will publish an electronic edition of Copy D in the near future. Like all the illuminated books in the Archive, the text and images of Milton Copy B are fully searchable and are supported by our Inote and ImageSizer applications. With the Archive’s Compare feature, users can easily juxtapose multiple impressions of any plate across the different copies of this or any of the other illuminated books. New protocols for transcription, which produce improved accuracy and fuller documentation in editors’ notes, have been applied to all copies of Milton in the Archive. With the publication of Milton Copy B, the Archive now contains fully searchable and scalable electronic editions of sixty-eight copies of Blake’s nineteen illuminated books in the context of full bibliographic information about each work, careful diplomatic transcriptions of all texts, detailed descriptions of all images, and extensive bibliographies. In addition to illuminated books, the Archive contains many important manuscripts and series of engravings, sketches, and water color drawings, including Blake’s illustrations to Thomas Gray’s Poems, water color and engraved illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy, the large color printed drawings of 1795 and c. 1805, the Linnell and Butts sets of the Book of Job water colors and the sketchbook containing drawings for the engraved illustrations to the Book of Job, the water color illustrations to Robert Blair’s The Grave, and all nine of Blake’s water color series illustrating the poetry of John Milton. As always, the William Blake Archive is a free site, imposing no access restrictions and charging no subscription fees. The site is made possible by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the continuing support of the Library of Congress, and the cooperation of the international array of libraries and museums that have generously given us permission to reproduce works from their collections in the Archive.

Morris Eaves, Robert N. Essick, and Joseph Viscomi, editors

Ashley Reed, project manager

William Shaw, technical editor

Continue readingBlake/An Illustrated Quarterly (sometimes known as the Blake Quarterly, BIQ, or just Blake) is an academic journal that was founded in the late 1960s by Morton Paley at UC Berkeley; in the years since, its production offices (actually office) have moved first to the University of New Mexico and then to its present home at the University of Rochester with the other editor, Morris Eaves, who is also co-editor of the Blake Archive.

We are currently print only, but are negotiating the journey from hard copy to an electronic existence. Our first task is to digitize our back issues, currently cloistered in a windowless storeroom but before long hopefully available on the web. After that we’ll turn our attention to getting new issues online.

Along with chronicling this transition, I’ll post about Blake-related events that come to our attention. This year, the Tate is planning to display works from Blake’s one-man exhibition of 1809, and from April to June there will be a major exhibition in Paris.

Continue reading

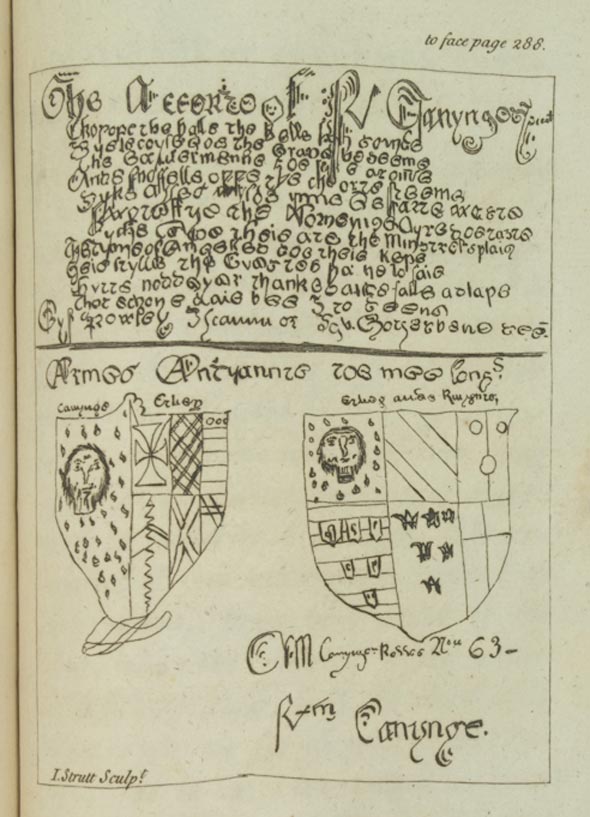

Thomas Chatterton. Poems, Supposed to Have Been Written at Bristol, by Thomas Rowley, and Others, in the Fifteenth Century. London: T. Payne and Son, 1778.

Via the “Book of the Month” feature of the Rare Books Library at the University of Rochester. Curator Pablo Alvarez’s description of this volume (and more pictures!) can be found here.

Thomas Chatterton: genius, forger, suicide, and Romantic hero. Chatterton created the 15th century priest and poet, Thomas Rowley, forged manuscripts of poetry, and published them as real historical finds (complete with marginal glosses and explanatory footnotes). The image above depicts an engraving of one of Chatterton’s forged manuscript pages. As Alvarez describes, his hoax was well researched:

Chatterton examined medieval manuscripts not only from St. Mary Redcliff Church but also from local libraries and bookstores in order to create a fifteenth-century hand. He consulted medieval glossaries and etymological dictionaries to fabricate what he erroneously thought was a version of fifteenth-century English—his medieval vocabulary included some 1,800 words. More dramatically, he did not hesitate to manufacture manuscripts that looked old by rubbing the parchment with dirt or dying it with tea. If he didn’t produce a manuscript, he simply claimed that the poems in question had been copied from an original version that existed elsewhere (Grafton, 1990: 50-3; Rosenblum, 2000: 57-105).

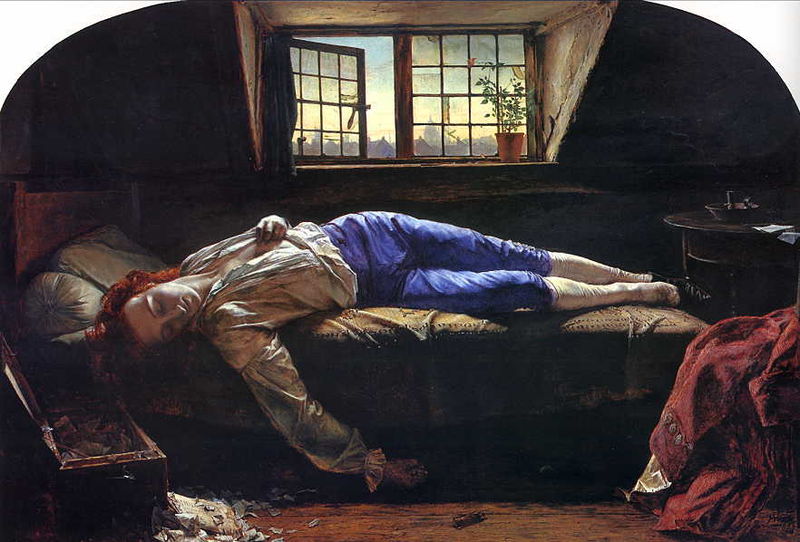

Chatterton died at the age of 17 by arsenic, an apparent suicide (although Nick Groom argues that his death may have been accidental, as arsenic was used to treat sexually transmitted diseases). His poetic genius and tragic death made him a Romantic hero; the “marvellous Boy,” as William Wordsworth calls him in “Resolution and Independence,” was commemorated in works by Percy Shelley, Samuel Coleridge, John Keats, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Henry Wallis, The Death of Chatterton. 1856.

——–

Grafton, Anthony. Forgers and Critics: Creativity and Duplicity in Western Scholarship. London: Collins & Brown, 1990.

Rosenblum, Joseph. Practice to Deceive: The Amazing Stories of Literary Forgery’s Most Notorious Practitioners. New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2000.

Continue readingA research project of the Humanities Division of the University of Oxford, the Electronic Enlightenment invites you to “explore the original web of correspondence: read letters between the founders of the modern world and their friends and families, bankers and booksellers, patrons and publishers.” While EE clearly defines itself as a digital project, “a ‘living‘ interlinked collection of letters and correspondents” (FAQ), its foundation is made of paper; that is, the primary source of its content (at this point) have been the print editions of academic presses.

From “Principles of the Edition:”

To date, most of the content of EE has been provided by printed editions of correspondences from academic presses worldwide; nevertheless, it should not be viewed simply as an aggregation of these editions. Rather it is a database of individual letters and correspondents that can be searched or browsed as a complete collection.

From the “Introduction:”

EE has as its foundation major printed editions of correspondence centred on the “long 18th century”. From the correspondence itself, the supporting critical apparatus and additional research carried out by EE, we have developed a set of information categories, from dates and names to textual variants — indeed, any piece of information that contributes to our understanding of the documents. The data captured within these information categories enriches EE as a digital academic resource, by creating an intricate network of connections between the documents.

EE provides access to over 53,000 letters and documents from several centuries (the earliest letter is from 1619), correspondent bi0graphies, and explanatory notes (depending on the source edition, these might be editorial, textual, linguistic, or general notes). The searching capabilities appear extensive; users can search for letters by content (words or phrases), author name, place of origin, date (including day, month, and year), recipient, and the city or country where it was received.

Moving beyond its bookish roots, EE openly invites user collaboration. Users can supply missing information about biographies, dating of documents, locating correspondents, and translations. Readers can submit new letters for electronic publication. Scholars can even develop their own born-digital projects. From “Contributor Services:”

EE will provide a creative space for scholars to develop new born-digital critical editions of correspondences online. It will offer a central area where progress reports can be posted or linked, discussion lists for collaborators and testers maintained, and project results published. When prepared, these editions can be integrated seamlessly into the full collection of EE.

EE offers born-digital editions the possibility of publishing correspondence collections online, integrated into our network of biographical and documentary links.

Despite all of this exciting, collaborative coolness, however, access to the project seems to be by institutional subscription only. (Even the “free trial” available through Oxford University Press seems to be tied to institutional affiliation.)

Continue readingLisa Spiro at Digital Scholarship in the Humanities started her review of the digital humanities in 2008. She starts with the “Emergence of the Digital Humanities,” and considers NEH’s establishment of the Office of the Digital Humanities as “giving credibility to an emerging field (discipline? methodology?).” The next section is (fittingly) “Defining ‘Digital Humanities,'” where Spiro traces critical key definitions of the “Digital Humanities,” such as discussions of whether it is a method, field, or medium. The last section of this first part of her review is “Community and Collaboration,” which surveys virtual networks of scholars, Humanities Research Centers, and Twitter as “a vehicle for scholarly conversation.”

Continue readingIn 2006, the University of Rochester started The Humanities Project, “an interdepartmental endeavor designed to champion work by Rochester faculty in all fields of humanistic inquiry.” Each year, several projects are selected to receive funding to sponsor speakers, films, symposia, conferences, panels, and exhibitions.

Last fall, one of the projects was on the work of John Dryden (Restoring Dryden: Music, Translation, Print). Faculty from the departments of English, Modern Languages and Literatures, Art/Music Library, and Rare Books, Special Collections and Preservation planned a series of events that included relevant undergraduate courses (on drama, literature, translation, and the history of the book), evening concerts (chamber arrangements, arias, and songs), dramatic readings, and panel discussions of Dryden’s poetry and drama.

In conjunction with the humanities project, Pablo Alvarez curated an exhibit in The Rare Books Library (John Dryden and the Book: 1659 – 1700). While this brick-and-mortar exhibit consists of real books in glass cases, Alvarez also highlights several of Dryden’s books in the Rare Books virtual exhibit, the Book of the Month. Alvarez presents really nice digital images of each book, and gives a thorough bibliographic account, including relevant biographical information of the author, printer, and other key figures in the book’s production, contemporary catalog descriptions, general plot summaries, a bibliography of sources, and how the item ended up in the collection.

The selected Dryden works are here:

A bit of Blake trivia: Blake made woodcuts for Thornton’s Pastorals of Virgil (1821). Proofs from these woodcuts were at one time bound with Blake’s manuscript An Island in the Moon, although they have no relation to the content of the MS, and were removed in 1978 (when the MS was rebound).

Continue readingFrom the Romantic Circles Blog : A fascinating exhibit at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts in Birmingham focuses on how the changing technologies of the Industrial Revolution altered societal values and created a new spirit of pride and nationalism in England. From their website:

The face of Britain changed beyond recognition in the nineteenth century following intense industrialization and urbanization, advances in agriculture and developments in international trade and finance. New private banks employed celebrated engravers to create intricate and beautiful banknote illustrations, portraying aspects of the changing Britain and illustrating a sense of national pride and civic identity.

This extraordinary exhibition of banknotes, tokens, medals, paintings, prints, silverware, pottery, and models of locomotives and ships, reflects those monumental changes and provides an invaluable insight into the economy and society of the time. A collaboration with the British Museum, it also features items lent by the Science Museum, Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, Wolverhampton Art Gallery and the Cadbury Collections of nineteenth-century Britain.

The exhibit offers a glimpse into a changing society that saw the effects of technological evolution more rapidly than ever before. Blake himself was invested in the technologies of his time, particularly given his belief that he invented a new printing method. The exhibit runs from March 7, 2008, until March 6, 2009.

Continue readingA discussion on the listserv for the North American Society for the Study of Romanticism (NASSR) has turned up some fascinating musical adaptations of Blake’s work, ranging from indie rock to garage to singing Beat poets. Contributors to the discussion and the links they provided are below.

James Rovira: The discussion began with his announcement of a CD put together by William Blake and the Human Abstractions, which includes some of their work for an Blake exhibit at the Martin Art Gallery at Muhlenberg College last June. Information about ordering the CD is available on their MySpace page. You can hear two songs from the CD, “Spring” and “The Sick Rose,” on the page. Rovira notes that the CD, according to the exhibit’s curator, will include “Spring,” “The Sick Rose,” “Night,” “The Human Abstraction,” “Chimney Sweeper,” “The Ecchoing Green,” “Ah! Sunflower,” “Little Boy Lost/Found,” “Infant Joy/Sorrow,” “Hear the Voice of the Bard!”, and an improvisational piece, “Wings of Fire” (also the title of the exhibit). Although the MySpace page gives the release date as Fall 2008, I was unable to locate any further information about whether or not it’s actually out. You can e-mail brkirchner_AT_hotmail.com for more information. Songs are also available for purchase on iTunes, although I’m having some trouble searching for it. An iTunes search for “William Blake” did, however, pull up some Patti Smith songs, including “My Blakean Year,” which is well worth a listen.

Dennis Low pointed the list to this interview with Sparklehorse’s Mark Linkous from the BBC Culture Show, who has been heavily influenced by Blake’s poetry in his life and music. The interview includes a performance of “London,” as well as Linkous reading an excerpt from “A Poison Tree.”

Avery Gaskins noted that The Fugs, a folksy band with a good dose of garage rock/psychedelic sound, set “Ah! Sun-flower” and “How Sweet I Roamed” to music. I was able to find a recording of “How Sweet I Roamed” on Last.fm.

Peter Melville provided a link to Kevin Hutchings’ essay on the musicality of the Songs of Innocence and experience from Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net (RaVoN). Hutchings has also released a CD, “Songs of William Blake,” available for purchase here.

Misty Beck brought up Greg Brown’s versions of some of the Songs, as well as Allen Ginsberg’s renditions, recorded in New York December 15, 1969, and available for your listening pleasure at PennSound. Beck also reminded me of Iron Maiden’s cheesy, and oddly catchy, adaptation of Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner.”

Steve Jones points us to poet Anne Waldman singing “The Garden of Love,” for the Romantic Circles Poets on Poets series. Download the MP3 here.

Dorothy Wang and David Latane both suggest classical composer William Bolcom’s Songs of Innocence and Experience, available at Amazon.

Nelson Hilton mentioned the Songs hypertext site, hosted by UGA. Choosing a song pulls up the page along with a piper icon in the corner. By clicking on this icon, you can access musical adaptations of that song by musicians like Finn Coren, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Ginsberg, and Gregory Forbes.

Timothy Morton brought up Jah Wobble’s album, The Inspiration of William Blake, available on Last.fm here. Tangerine Dream’s version of “The Tyger” is also available on last.fm via this YouTube video that is sure to liven up any party.

Last but not least is Joseph Viscomi’s stage adaptation of An Island in the Moon, with songs by Margaret LaFrance set to flute, piano, and voice in traditional 18th century ballad formats. The play, performed at Cornell in 1983, is available here.

Update: Melissa J. Sites and Dave Rettenmaier, the Site Manager for Romantic Circles, has consolidated all the recommendations from the NASSR post within the Scholarly Resources section of Romantic Circles, including some of the adaptations I didn’t get to for folks like Byron and Percy Shelley. The list, Pop Culture Interpretations of Romantic Literature, also includes suggestions from an earlier discussion (about 10 years ago) on the same subject.

Continue readingVia A Repository for Bottled Monsters (“An unofficial blog for the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, DC.”): The Washington Post has a story up about the Smithsonian’s efforts to join the digital age, starting with “Smithsonian 2.0,” a gathering of Smithsonian curators, staff, and such digital luminaries as Clay Shirky (we wrote about an interview with him here), Bran Ferren (co-chairman and chief creative officer of Applied Minds Inc.), George Oates (one of the founders of Flickr), and Chris Anderson (editor in chief of Wired). [Update: Dan Cohen was also there, and wrote about his responses here.]

Probably the most provocative point raised in the article is the role of the curator, or expert, in the Smithsonian’s digital future. Institutions like museums (or presses) have traditionally occupied the role of gatekeepers (to steal a term from mass communication), choosing “the best” from the masses to display (or sell). For example, less than 1% of the museum’s 137 million items are on display. As many have pointed out, digital technologies change how information is generated and shared, and within the context of 2.0 technologies, crowd-sourcing, and remixing, the role of the expert and conceptions of authority are also transforming – transformations actively “promoted” in the digital humanities imagined in the forward-thinking “Manifesto” from UCLA’s Mellon Seminar in Digital Humanities:

Digital humanities promote a flattening of the relationship between masters and disciples. A dedefinition of the roles of professor and student, expert and non-expert. (paragraph #20)

For those involved in historically curatorial institutions like museums, archives, and the ivory towers of higher education, an identity crisis looms. Anderson’s message to the Smithsonian is that gatekeepers “get it wrong,” the influence of curators will never be the same, and that in fact, the “best curators” have not yet emerged from the crowd.

“The Web is messy, and in that messiness comes something new and interesting and really rich,” he said. “The strikethrough is the canonical symbol of the Web. It says, ‘We blew it, but we are leaving that mistake out there. We’re not perfect, but we get better over time.’ ”

The problem is, “the best curators of any given artifact do not work here, and you do not know them,” Anderson told the Smithsonian thought leaders. “Not only that, but you can’t find them. They can find you, but you can’t find them. The only way to find them is to put stuff out there and let them reveal themselves as being an expert.”

Compare this optimism, emphasis on shared knowledge, and confidence in the hidden expertise of the public with a new project called brainify.com, a social-bookmarking site only for academics, or more precisely, those with university email addresses (which already excludes a great number of academics in the position of adjuncts, who often don’t get university email accounts). The Chronicle of Higher Education just ran an article about the site’s debut (“‘Social Bookmarking” Site for Higher Education Makes Debut”), and cites creator Murray Goldberg’s rather different take on the value of public contributions:

Mr. Goldberg said that he wanted to focus on solidifying the site’s functions for students and faculty members before exploring the possibility of expanding membership. “As soon as we open up membership for bookmarking to a broader audience, we risk dilution of the quality of the site.”

Hm, so Anderson sees expertise revealing itself from within the public, while Goldberg fears a dilution of “quality.”

In general, I agree with Goldberg’s assertion that “the world needs an academic-bookmarking tool.” Filters are important; they allow users to manage and control the overwhelming amount of information available on the web. Clay Shirky asserts that the charge of “information overload” is actually a problem of inadequate filtering. And as a graduate student and instructor, I can understand that academic needs and interests might vary from that of the general public, necessitating different sets of tools. But ultimately, I question whether the deliberate construction of a “walled garden” (as Melanie McBride calls it) is the best way to meet the varied needs of academics. That is, using exclusivity to order and manage the “messiness” of the web – trying to avoid the strikethrough – is not truly engaging the huge potential for networked knowledge.

I’ll leave Anderson with the final word:

Continue reading“Is it our job to be smart and be the best? Or is it our job to share knowledge?”