This interview was conducted by Elizabeth Effinger, who has edited and condensed it for publication. It will also appear in the fall 2023 (vol. 57, no. 2) issue of the Blake Quarterly.

The year 2022 marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of the publication of Helen P. Bruder’s William Blake and the Daughters of Albion (Macmillan, 1997) (hereafter WBDA), the first book that brought feminist criticism to bear on Blake studies. Bruder’s WBDA wrestles with Blake’s complex representations of gender and sexuality. While earlier essays brought much-needed critical focus to Blake’s representations of women (see Susan Fox and Anne Mellor),[1] Bruder’s book-length study argued for a radical feminist spirit in his works. This strident call to arms would advance Blake scholarship in exciting new directions, and WBDA has been widely cited ever since. Bruder is also the editor of Women Reading William Blake (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007) and prolific co-editor with Tristanne Connolly of four collections: Queer Blake (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), Blake, Gender and Culture (Pickering & Chatto, 2012), Sexy Blake (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), and Beastly Blake (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). Currently, she is an independent scholar living in Oxfordshire. I met with her on 3 October 2022 at St. James’s Church, Piccadilly, in London, where we talked in the vestibule near the font where Blake was baptized in 1757. In the interview that follows, Bruder reflects on WBDA and what has changed in Blake scholarship since then.

EE: How did you come to Blake? Do you have an earliest memory of Blake?

HB: I had a very religious upbringing. The thing that got me into Blake was I wanted to continue being a Christian but adult life buffeted my basic faith. … My early education was woefully bad but when I read my first Blake poem at Brookes University, I liked it so much. I was just seized immediately. We did all of Songs. It was probably the whole experience of studying that collection of poems. I had two fantastic teachers. And then I just knew. First Songs and then Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

EE: I think those texts are still the gateway drugs into Blake.

HB: Marriage of Heaven and Hell is the text that just gets you. It’s because you can understand it, or you think you can understand it. There are some bits where there aren’t weird characters immediately. The narrative is so important—that’s the incentive of the Proverbs. … I was lucky because the two people that taught me Blake, one of them was a Marxist, so he wasn’t interested in religion, and the other one had been a priest. So, I had two good influences, each taking me in completely different directions with Blake.

EE: What was it about Blake that seized you?

HB: Initially, it was the idea that you could have a very vibrant religious faith, but it didn’t have to be attached to moralizing, or judgmentalism or salvation in the sense of sorting the sheep from the goats, and an incredibly inflated sense of what it is to be human and divine in yourself at the same time, but for that to mean something completely different from what it might mean in the church.

That’s what seized me emotionally, but that isn’t what I wrote about ever. Until now. That’s the latest project. That’s what Tristanne Connolly and I are doing now: a book called Blake Sees Jesus. And I see it as a kind of a completion of or being a little bit more honest about what my actual initial attachment was to Blake. It feels like coming full circle.

EE: I’ll loop back to your new project later, but first let’s talk about the book that started your long career in Blake studies. Your widely cited first book, William Blake and the Daughters of Albion, celebrates the twenty-fifth anniversary of its publication this year, and is the occasion for us sitting down and having this conversation. Why do you think that this book was considered such a game changer in Blake scholarship?

HB: I think it’s because of the timing. WBDA was published in 1997, but, like I say in the book, feminist Blake studies came a bit late. So, I think somebody had to write this book. It wouldn’t have to be written particularly in this way, but I was full of this sense that there was something terribly unjust and wrong in Blake scholarship, and I wanted to sort it out. I put that down to my religious upbringing. It’s a bit like what Jeanette Winterson says: once you’ve preached inside the tent, whatever you do, you’re still preaching. I wouldn’t take such an emphatic tone now. I think the broad stroke of saying that feminists can be really good Blake scholars and we’re going to illuminate things that you’ve ignored is a fair point, and one that is really well proven.

EE: Personally, I enjoyed your choice of voice; it felt charged, like Blake’s “awake! awake! awake! / Jerusalem thy Sister calls!” (Jerusalem 77.1-2, E 233). Your criticism of misogynistic interpretations of The Book of Thel was especially eye-opening for me.

HB: I really didn’t feel like it was a choice. When I wrote the chapter about The Book of Thel, I felt that femininity shouldn’t be so despised, because that’s what motivated so much of that criticism that had grown up around it. It was obvious once you plunged into it; it’s not just one person, it’s like fifty people. Sometimes you must point out the obvious. I don’t know if I’d come down on the same side in my interpretation of the poem now. Maybe I wouldn’t. But then, critics seemed to hate this character [Thel] and really, all she’s doing is saying “I’m not sure.” I took the same sense of indignation because I sort of felt it.

EE: That sense of indignation comes through! I’d say your writing in WBDA has teeth. It also strikes me that your rhetoric echoes the way you see Blake’s voice as socially engaged with his world, a direct rebuttal to those critics who see Blake as someone speaking only to himself. I think that’s what I really enjoyed about your book, that sense of how affected you were by the material. It’s one that resonates with my own encounter with Blake’s work, that it just gets under your skin.

Something else I appreciated was your methodology of paying attention to the “cultural effluvia” of Blake’s day, as you put it. What’s the attraction to these sources?

HB: Traditionally, there’s a lot of talk about Blake as a genius. The idea that he wasn’t affected by the time of his writing is obviously profoundly wrong. You can be both, which is what he is, because he’s a genius, giving us a genius sense of history and of his own time. But that seems obvious, doesn’t it? There were all these things that are happening around him. Everybody’s interested in political history, and I’d just like to say, well, there’s other history too.

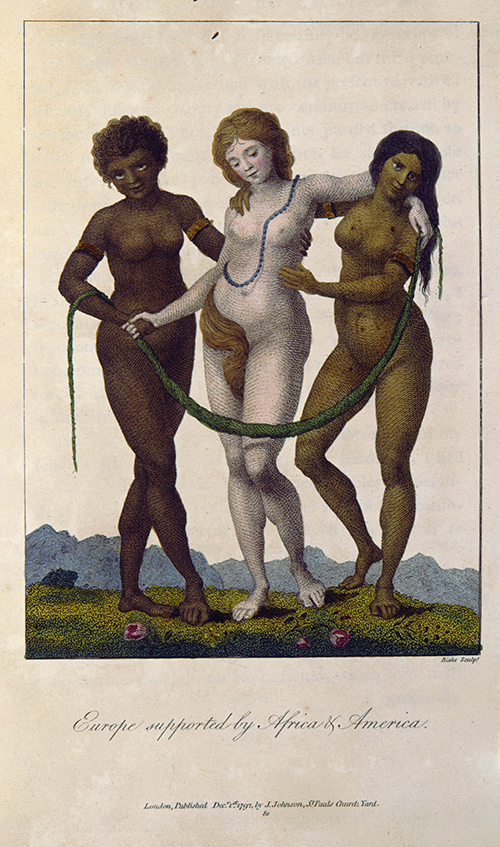

So, let’s go back to the basic things. Take Blake’s Europe, for example. I mean, you’re in the middle of a European war, and a queen [Marie Antoinette] has been guillotined and very close to the production of this poem. Could there be a connection? There were loads of pornographic cartoons of the queen. Do you think it’s possible this man [Blake], living in London, looking at pictures, may have seen one of them? It was not hard to find. You might not be interested in it, but it’s literally not hard; there’s loads of political pamphlets. Do you think you might have read any of them? There are loads of political cartoons, and they’re obscene some of them. Do you think that could have anything to do with the bodies as they appear in Europe?

In WBDA I ran out of energy and space. I would have liked to get on to the Urizen books because they’re more complicated. But also, the argument about what’s human or not human in Blake, about what embodiment is and how that affects identity, that’s everywhere in Blake’s work and I didn’t get to it.

EE: What do you think has changed most in your own work, or in Blake scholarship, since the publication of WBDA?

HB: In thinking about how things progressed after this book, I think the most striking thing is the collaborations. In looking back at the end of WBDA, it’s a little bit sad when I’m saying I feel like I’m speaking into a void, and there’s not a big conversation of it. There genuinely wasn’t. That’s probably the biggest difference now. I think there’s more collaboration now, and different kinds of collaboration.

Back then, I think there was much more of a sense of there being an establishment, a genuine establishment that really wasn’t open. It was the prescribed readings, and that some things were appropriate, and some things weren’t, and some works more important than others. And we all know what the important ones are and which ones aren’t. And the visual must be separated from the poetry. And if you’re an expert on this, you can’t write about that. It’s different now.

I think I always start with the most obvious things and work out from that. I’m never going to have the same kind of insights as somebody who knows a great deal about Christian iconography. I just come at it with my own eyes and am informed by at least my relatively wide knowledge of Blake.

I’m quite pleased with collections that I’ve done since WBDA. With Women Reading William Blake, I wanted to get as many of these women that haven’t necessarily been seen together as part of a critical landscape. And then it brought me to meet other people. Tristanne Connolly and I have collaborated multiple times, which has been fantastic.

I think collaboration is a very good way of seeing directions open up. Because when you ask people what they want to write about, beyond offering them the broad theme, you’re asking “What would you like to say?” And you, you’re learning; you’re not prescribing. If you invite people under a broad theme to write something, you don’t know what you’re going to get. With Beastly Blake, Tristanne and I thought that might be one kind of book, and it turned out to be another kind of book. But then also, you’ve got to be careful that you don’t become part of the problem, and just keep on asking the same people, or people that you know you’re going to agree with.

EE: It’s just as Blake says: “Without Contraries is no progression” (Marriage 3, E 34). It sounds like your ongoing interest in collaboration, as a concept and as part of your own scholarly practice, folds back into some of the ideas about what you were pushing against in this book, around the gatekeeping and policing in Blake studies at the time.

HB: That’s exactly right. I think the sense is that Blake is this genius, and then he’s taught to us by these other genius characters, these “great fathers” of Blake studies. But I don’t think so. I think we probably learn a lot more if we are all toiling in the field together.

EE: How would you feel if you were called one of the great mothers of Blake studies?

HB: (laughing) I don’t know. I guess that would be nice, but only in the sense that that’s just the beginning. I think there was a good point to be made in WBDA, but I could have done it without quite swinging the hammer so much. And I think it needed to be followed by all these things that have proliferated into these multiple voices. That’s the way it needs to be.

EE: Collaboration is a form of partnership, and that also makes me think about the connections with the public and forms of public scholarship. Not only do we have these multiple collaborative voices in Blake scholarship, but we also have public engagements with Blake. I’m thinking even beyond the widely recognized scholarly resources that make Blake’s work freely available (e.g., the Blake Archive)—for example, Jason Whittaker’s Zoamorphosis blog, the free online journal VALA from the Blake Society, and even books on Blake aimed at a wider audience. These all potentially shape the image of Blake in the popular imagination. Is there anything about Blake that you think still needs to be reshaped in the popular imagination?

HB: Going back to first principles and things that are obvious is important. Take the role of Catherine Blake. How can it possibly be that this person who collaborated with Blake, who helped produce his creative work for his entire life, is cut out? For many years, Catherine’s role has only been acknowledged in a minor way, as having done the printing and a bit of coloring. But that is clearly not going to be the only way that this partner influenced Blake’s genius. It’s just another bit of the mythology which still lingers, but it can be changed.

And then there’s also the generic hierarchy within Blake’s own work. For example, the Thomas Gray watercolours for Ann Flaxman, why are they not taken more seriously when people are trying to have a whole sense of Blake’s visual progression? I think that is because they see the watercolours in some broad sense of feminine aesthetic. These are just things that are obvious, but still, we could do something about it.

EE: Let’s talk about what’s changed in the last twenty-five years—or maybe what hasn’t. Do the kinds of critiques you make about Blake studies still hold true today? Are gender and sexuality still neglected in this discourse? Are there other areas that you consider to be neglected in Blake scholarship?

HB: I haven’t reached a fixed position about that. In many ways I’m not the right person to ask. I’ve been an outsider, a passionate and interested amateur, for years now and I genuinely feel others are in a much better position to answer this question. Perhaps also because my thinking about gender and identity refuses to catch up with the virtual world, and future directions now can only be envisaged, I think, by digital natives.

I would have liked to see some more book-length studies on Blake and gender and sexuality. There’s lots of articles. Loads of people have written great things, and the issue of gender doesn’t tend to stay entirely on the margins now, which is good. I’d also like to see something like this on the longer poems.

I think what VALA, the Blake Society journal, is doing is fantastic; its first issue was about women and gender. That was great.

EE: Do you think there’s something about Blake’s treatment of gender and sexuality that makes it resistant or inhospitable? Why are people not writing these books?

HB: I wonder if academics are not writing these bigger books because maybe academics think it [Blake’s treatment of gender and sexuality] is too simple, or it’s too obvious or it’s too abundant. Because it’s absolutely in everything that he writes or draws. I know it’s clever to find something that’s hidden, that nobody else has found, but this is hiding in plain sight. It’s not just in these obvious poems—The Book of Thel, Visions of the Daughters of Albion—it’s in every poem, in every artwork, and in probably every annotation, and in every bit of biography, and I feel like it should be woven into the mix of whatever. … Whatever your interest is, you must have an interest in this too, because that’s what Blake puts at the centre of everything he speculated about, whether it’s aesthetic, or religion, or politics. It’s never on the margins of his thought, even if it is on the margins of his interpreters’.

EE: One of the things that WBDA does is boldly call out scholarship for the absence of feminist readings of Blake’s work. What was it about the fact that it was the 1990s that struck you as part of the scandal?

HB: The work that was going on in literary criticism was just part of a bigger women’s movement. I think we all kind of thought the revolution was about to occur. And once you explained how appalling or dreadful this sexism was, of which these men interpreting Blake were just a tiny example, that everything would change. Also, it wasn’t just about feminism; it was about that larger sort of radical politics at the time. And Blake was obviously, as he still is, a bit of a totemic figure for all revolutionaries.

EE: So, you felt like you were part of a revolution?

HB: Yes, and I was both right and wrong. History has been different. There’s been a gender revolution, maybe without the sexual revolution, without those kinds of changes more broadly in society. … It was definitely a motor for writing this book.

EE: Looking back at this book, I was wondering how your own cultural political moment might have been shaping the tone and your focus here. Were you involved in any kind of political activism at the time?

HB: Yes. But it was generally kind of depressing. I don’t think anybody I ever voted for was ever elected, and then we got Tony Blair! So, we carried on, going on numerous marches, trying to end violence against women, to reclaim the night, to obtain affordable childcare, and so on.

I had this sense that the women’s movement wasn’t changing society quite as quickly as we wanted, but the academic world was the one place where actual change was happening, and it was very positive. It doesn’t sound like much now, maybe, but once women’s history started to be taken seriously, and there were whole conferences just about women’s history, this was very exciting. There was the feminist academic network, and this was very exciting.

EE: You were building that New Jerusalem.

HB: It was a real stark change, and it took off in the 1990s. Personally, it was very exciting. I felt part of it, that there was a real cultural activity that was gathering steam.

EE: It seems like your work has run parallel to other movements of change. Do you see a through line with what you’re doing here in your first book running into those subsequent projects?

HB: If you had walked up to the person that wrote this book [WBDA], I would never have believed we’d be where we are now. This is really great, you know? I wouldn’t have believed that there’d be so many women writing about Blake that you could pitch to a publisher, “I want to do this book, Women Reading William Blake,” and they would say, “That’s good.” Or that then you go back and say, “I want to do one called Queer Blake,” and they would say, “That’s great!” This person wouldn’t have believed that.

EE: I’m glad you bring up Queer Blake (2010), your edited collection with Tristanne Connolly, which I think stands as another landmark in Blake studies. Building on the important work begun a decade earlier by Christopher Hobson in Blake and Homosexuality (Palgrave, 2000), your book brings the insights of queer theory, rooted in gay and lesbian studies scholarship, to bear on Blake. Like Hobson’s book, we can see Queer Blake as a key event that helps fold Blake into a larger queer intellectual history. But perhaps even more importantly, this collection created a space that fostered new lines of thought and queer ways of engaging with Blake’s work that continue to energize queer approaches to Blake today. What struck you as “queer” about Blake? What kind of new intellectual work was afforded by queering Blake?

HB: Oh, come on, what isn’t queer about Blake!? I’ve always specialized in revealing the screamingly obvious and Blake’s queerness is surely more apparent than even his, what shall we call it, proto-feminism. His visual art is a Pride parade of gaping garments, sly gestures, naked audacity. If you can name it, I feel Blake gives us a glimpse of it—often from some very alarming angles. And more seriously, I think Blake’s obsessional belief that he “must Create a System, or be enslav’d by another Mans” (Jerusalem 10.20, E 153) is especially true and urgent when he confronts and creates gender systems. Perhaps surprisingly, I’ve never been very bothered by the seemingly tedious heterosexist inequality of his zoas and emanations. Because, yes, they are gendered asymmetrical pairings, but they erupt and fragment and dissolve and re-form in queer ways, almost as soon as the concept emerges. I’ve also not really been troubled by the “Four Mighty Ones” which there “are in every Man” (Four Zoas 3.4, E 300) because there’s a good chance this refers to a universal human condition, which creates infinite possibilities for interpersonal connections between infinite identities.

Of course, Albion in Blake’s lifetime was not a gender-fluid utopia any more than it was a feminist one—and sexual power always matters—which I guess is why much of the early scholarship rightly focused on the political and criminal aspects of same-sex relationships, in a historical context, and so on. Yet again, Blake studies was a bit late to this party, the queer party, and I still remember how surprised and delighted I was seeing Chris Hobson’s book on the shelf in Blackwell’s in Oxford around the year 2000. There probably should have been other people working to forward this direction in Blake studies but after Women Reading William Blake (2007) I thought, why not? So, I pitched Queer Blake to Tristanne Connolly, she embraced it wholeheartedly and our wonderful co-editing relationship began. I love what that collection represents: an eclectic, open-minded, thoughtful, and imaginative first flourish. Now, I’m very content to sit back and see where newer, younger writers and artists go with queer Blake!

EE: Pandemic aside, I was really struck this particular year, 2022, with how we are living in a very scary time. Politically, in America, we’ve just witnessed the shock of the historic Supreme Court overturning of Roe v. Wade, which declares that the constitutional right to abortion no longer exists. Throughout your work, and especially foregrounded in your first book [WBDA], you’re showing us that Blake is somebody who is thoroughly interested in those relations between sexual politics and political power. Is there something about Blake that can help us in this moment where it does seem like gender and sexuality are coming into all sorts of trouble with power? If so, what kind of lessons?

HB: That’s very profound, isn’t it? Because in some senses, there is infinitely more freedom—for some people clearly more than others. And that’s great, but that’s often at an individual level. And if political structures can change a law of that kind, identity politics are hitting up against the end of a boot. It’s frightening. I think Blake could help us navigate every contemporary issue. If everyone who was making the laws had read Blake’s comments about laws, our current systems might be better.

EE: Tell me about which of Blake’s texts are most on your mind these days. Is there something that you keep coming back to?

HB: The Urizen books, because I don’t understand them. I’m not sure I understand any of the epic epics; I’ve read them many times, and I’m not sure I do. But for some reason, the Urizen books I understand the least. I do find that there’s some of the most disturbing visual images in those three poems. Maybe that is partly because of the times we’re in.

Also, for the Blake and Jesus project, I’m just enjoying looking at endless pictures of Jesus. Because they are absolutely fantastic and really surprising. I’m really interested in where there’ll be a gospel story and then Blake will step just outside of the text, just beyond the narrative margin and imagine, and then picture, things about Jesus which aren’t quite stated but which he uniquely sees. These are very embryonic ideas now, but I guess I’m trying to get a glimpse of what it means to have divine visions in times of trouble.

That’s the other thing that’s obvious: just how much Blake did. Now that I’m fifty-five years old, that feels quite old, I like to see how much somebody [Blake] managed to produce out of their human years and days. You know, it’s kind of a wellspring. I think I have a more free and ecstatic enjoyment of Blake now than I did when I was writing WBDA. Now, I think there’s a lot to be had just from the experience of the encounter with Blake. Especially with the visual art; it’s transformative as an object, as an encounter, and not just for the ideas.

EE: Tell me more about this new project on Blake and Jesus, and any other projects on the horizon.

HB: It started as an idea ages ago, but it’s now resurrected as a proper project, and I think it is very timely. I think Jason Whittaker’s book Divine Images (Reaktion, 2021) is really good and needed to be published. I think that when people who are not experts pick up a book on Blake, they should be able to understand at least some of it, and that’s a great introduction, and very richly illustrated.

For many years I’ve wished Tristanne [Connolly] and I could produce a coffee-table format book of Blake’s gospel pictures along with gospel texts. I spend lots of time in church bookshops and dream of something like that, Blake’s gospel, or even Blake’s everlasting gospel. So far, though, that’s not been practical, so until it is, we’re editing another diverse collection called Blake Sees Jesus. Each contributor focuses on a single image, which is reproduced, so it’s the beginning of a larger “Seeing Jesus” project. In the future, I’d like to continue the dialogue with people outside academia who’re interested in that mission, vocation, faith—not least because I’ve been spending a lot more time inside churches lately—but for now it’s a scholarly foray and seeking to see in that way is wonderful too.

EE: It sounds like your new project promises to reach out across the aisle, as it were, and break down some of the disciplined ways of thinking about Blake. And what a fitting place we are in [St. James’s Church, Piccadilly] to be hearing about this direction in your work.

HB: Once you start something with Blake, something else always emerges from this, and not just in terms of a new idea. It always leads to new experiences, just like this encounter we’re having here. I don’t think that Blake is a supernatural force that is changing the universe—(laughing) I’m not one of those people. But Blake is still very abundant and protean once you start to engage, so that’s kind of hopeful. And I do think it is interesting that the person that wrote this book [WBDA] would never have ever thought that this would be where we are now. I find that quite hopeful.

Thanks to Rev. Lucy Winkett and Rev. Dr. Ayla Lepine of St. James’s Church for granting us access to the space. All references to Blake’s text are taken from David Erdman, ed., The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake.

[1] Susan Fox, “The Female as Metaphor in William Blake’s Poetry,” Critical Inquiry 3.3 (spring 1977): 507-19; Anne K. Mellor, “Blake’s Portrayal of Women,” Blake 16.3 (winter 1982–83): 148-55.