My name is Esther and I’m an undergraduate student working for the William Blake Archive. I joined in January of this year. At first, I was working on the transcription for bb35.1.1 and bb35.1.2 of The Everlasting Gospel. After it was decided that the transcription didn’t have a place on the website right now, I transferred over to helping maintain the site’s collection lists.

The collection lists is a massive bibliography page for the site, containing a record of all the institutions we pull Blake’s pieces from, the specific pieces linked to their locations on the site, and works by Blake that are not included on the site yet but housed at their institution. I originally joined because I wanted to become more familiar with the site, and because I thought it would be a good experience for a field of work that I’m looking at (librarianship). Working with the collections lists has been an interesting journey. Sometimes it’s overly tedious, other times I find myself discovering something new. Sometimes I run into an issue due to my dwindling attention. For example, at one point I mistakenly tried to match the British Library’s collection list call numbers on Corsair. How disturbed I was on that Thursday evening when I couldn’t find any of the British Library’s holdings recorded on Corsair! My confusion was quickly resolved when I remembered that Corsair was the website for the Morgan Library & Museum. The best part about that experience was that I actually came pretty close to solving my imaginary problem — I managed to find potential candidates on Corsair to match “There is No Natural religion, copy A 1788-1794” listed under the British Library’s list. The first candidate almost matched because it listed its included copies: A-Z. The second candidate almost matched because the time period of its holding for “There is No Natural religion”, was 1788-1794. None of the candidates could have matched, since the call numbers were different, in a much larger sense, because they were on the website for the Morgan Library and Museum.

After laughing at myself for the ridiculous experience I managed to have, I started to think more about why I joined the Archive in the first place — why I started to like Blake in the first place.

The texts that introduced me to William Blake were Songs of Innocence and of Experience. I was a freshman in college, and I was enrolled in a class called British literature II, which studied English literature from the end of the eighteenth century and through the nineteenth century. My notes tell me that my initial impression of Blake was a deeply emotional and spiritual artist. I also reflected that he took a special interest in the cultural and economic shift that England endured during industrialization. The transition from innocence to experience in his most renowned and widely taught text not only captured a spiritual concept, but referenced the very real suffering of children that he witnessed in his rapidly changing country.

During my time as a member of the William Blake Archive I learned that the website aimed to appeal to a scholarly audience. While working on the collections lists specifically, I learned that the art and transcriptions presented on the website are comprehensive. While certainly some of the materials may be used to introduce Blake to students, the scope of the materials preserved on the site, and the details that the objects are presented with are definitely more accessible to those who’ve passed through initial levels of Blake study. The Archive is primarily for those who have decided to delve even deeper into Blake’s collaboration with other writers and artists, the style, publication, and distribution of his works during his life and after, and the different kinds of works he produced across the span of his life.

Studying just one section of the William Blake Archive “Robert Blair, The Grave”, for example, can teach you about art history, Blake’s disruptive relationships with colleagues, and, fast forward to modern times, the way in which Blake’s works are organized and distributed across institutions. Between the general description of “Robert Blair, The Grave (Composed c. 1805-08)” in Commercial Book Illustrations, and in Illustrations to Robert Blair’s “The Grave” (Composed 1805), Drawing and Paintings, I learned that twelve of Blake’s 1806 black and white designs for the poems are not engraved by him due to hostility between himself and the editor Robert. H. Cromek, and that they are kept in the collection of Robert N. Essick. Identical colored illustrations are kept in the Art Institute of Chicago, with disseminated ownership across private collections, due to a “dramatic rediscovery” of nineteen finished watercolor drawings in 2001, which were sold at an auction in 1836.

Indeed, if all of the details about publication and distribution enhances the website’s scholarly appeal, archival exhibitions serve a similar function. Exhibitions are a space to present a particular series or collection of Blake’s — and sometimes works not by Blake but related to Blake — along with literary and historical analyses that designs the exhibition to be teachable to an academic audience. The most recent exhibition, William Blake’s Biblical Illustrations (Apri-21), explores Blake’s philosophy of Christianity in detail by analyzing his art on the Bible. In one illustration, “Christ in Carpenter’s Shop,” Blake positions Christ in between his mother and father as a way to represent the center of feminine (human intelligence) and masculine (divine wisdom) attributes that Judaic thought conceptualized as the two main aspects of creation. The carpenter’s shop is then, “the World of Fact in which restoration is to begin” (Spector). This gallery then provides competing and converging analyses of the compass that Christ points down in the middle of the foreground. “Leslie Houlden (1: 94) and Morton Paley (56) both suggest that the compasses’ appearance here indicates the integration of reason with imagination or spiritual vision” (Micheal), which align them with Europe’s compass. However, while in Europe, symmetrical spheres indicated the mutual forces of imagination and reason coming together, in Carpenter, Christ points his compass asymmetrically. The compass emerges at the level of his “generative organs”, and “mirroring of form between the compasses and the legs of Jesus” (Michael), emphasizing imagination. This exhibition certainly draws on the general concepts associated with Blake’s character — his view on creation and the division of imagination and reason — while also providing a detailed repertoire of scholarly analysis to encourage deeper contemplation of familiar themes.

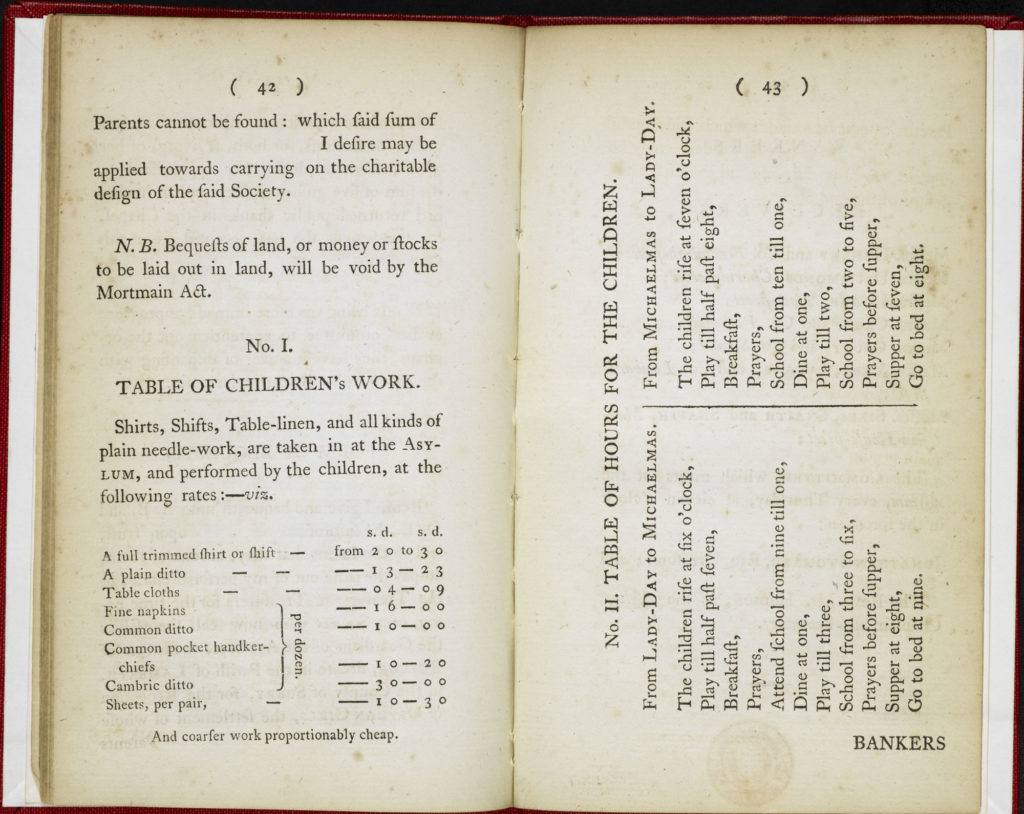

The Apr-21 exhibition references Europe’s spiritual themes in relation to Blake’s biblical illustrations, embedding the familiar themes evoked by Blake’s work in the religious philosophies of the time. During my work with the collection lists, I found myself contemplating the connection between Blake’s works, such as Songs, and the conditions of industrial England which they emerged from. This started as the fault of The British Library’s feature “An account of the Asylum for Orphan Girls”, in William Blake’s page, that I stumbled upon while checking the consistency of the call numbers between that institution’s online record and the Archive’s collection list. My feelings were further exacerbated by an industrial novel I just read a few weeks prior, North and South by Elizabeth Gaskell, for my English seminar. Like Songs, The novel also presented the abuses of industrialism alongside religious themes.

Reeling from this experience of learning and discovery, I was briefly inspired to propose an additional section to Archive, one where other genres by other authors, such as investigational reports and social commentary, can be put in dialogue with the issues at the philosophical center of some of Blake’s most widespread works. However, the more I thought about it, the more it seemed like an unrealistic project. Many 19th century works discussed abuses of industrialism, the shock of its transition, and the rights of children during that period, and could thus easily fit the criteria of what I wished to connect with Blake’s works. As Sarah Jones, the quarterly’s managing editor, put it, “where will we end, and where will we begin?” This could have been a good idea for an exhibition then — if not for the complexity of retrieving and gaining rights to these related works, and the more advanced scope of Blake Exhibitions in general that is perhaps out of my expertise as an undergraduate.

Therefore, I have decided to use the end of my reflective blog post to present a “mini-exhibition”, inspired by the British Museum’s An Asylum for Orphan Girls feature. The text I choose to put in dialogue with Blake is North and South. North and South is an industrial novel whose realism arises from the disconnect between the suffering of city children and factory workers and the communal ideals of “Christian Socialism” (Rajan) that radiates through the main character, a noble-minded Vicar’s daughter. Many of Blake’s poems in Songs may be considered “industrial poems”, and although they precede the 19th century novel North and South, they dealt with similar themes. Both attempted to reconcile the suffering of industrial children with religious thought. Indeed, images of everyday suffering are literally positioned alongside religious action in Blake’s poem, “The Chimney Sweeper”, “Crying “weep! ‘weep!” in notes of woe! / “Where are thy father and mother? Say?” / “They are both gone up to the church to pray” (2-4). Just as Europe imaginatively describes the clash between old feudal and aristocratic systems and enlightenment philosophy during the French revolution, forecasting a potential apocalyptic aftermath, North and South continually reiterates a tension between the old and the new from different worldviews. The old-world southern aristocracy fluctuates from being nostalgically ideal to realistically rigid, and the new-world of northern industrialism is liberating and mobilizing for some and unjust and compassionless for others.

An “apocalyptic aftermath” does take place in North and South, in the form of a disastrously failed revolution, which caused the arrests, suspensions and deaths of the factory workers, all the while leaving the labor shortage unresolved, causing a business crisis for the factory masters. Indeed, the chaotic and animalistic portrayal of the revolters may have pointed to Gaskell’s philosophical point about the fundamental impediments of revolutions. The factory worker’s violent attempt to impress their concerns on their masters, to undo a system they do not understand by force, is inferior to the change that can be achieved by sympathetic reconciliation between the classes. This viewpoint can be compared to interpretations of Europe, “Competing theories suggest that Blake may have intended the Continental Prophecies to highlight the inherent limitations of political revolutions” (MacLean, Robert Glasgow University Library Special Collections). The two primary characters the fueled the spirit of revolution represented in Europe, Los, a manifestation of the individual’s creative imagination, and Orc, a manifestation of physical revolution, suggests that, “Blake is arguing for a nonviolent revolution through the use of poetry to discover the creative imagination – or the poetic genius, – which inhabits every individual” (Hongxi Su). Indeed, Gaskell’s proposal to cultivate sympathy between different groups of people as a way of enacting social change speaks to Blake’s nonviolent approach to revolutions.

“The Meeting of a Family in Heaven”, Object 5, 1805, British Museum. The initial sketches of a piece are the truest representations of imagination in my opinion. So I put this here to highlight the ending of my piece that discusses Blake’s ideas concerning the imagination. Imagination as an antidote to the violent chaos of revolutions parallels Gaskell’s philosophy that sympathy is a superior method over rebellion to resolving inter-class differences, the article explains. The love and connection portrayed in Blake’s sketch thus connects Gaskell’s sympathetic argument and Blake’s creative argument while displaying the initial stages of Blake’s creative process.

Citations

Michael, Jennifer Davis. “Archive Exhibition: William Blake’s Biblical Illustrations (April 2021).” Archive Exhibition: William Blake’s Biblical Illustrations (April 2021).” The William Blake Archive, April 2021, http://www.blakearchive.org/exhibit/biblicalillustrations. Accessed 22 October 2021.

Rajan, Supritha. “North and South.” English 380: The Real World of Fiction. University of Rochester. Rochester. 21 October 2021. Discussion.

Maclean, Robert. “Book of the Month, William Blake, Europe: A Prophecy.” Glasgow University Library Special Collections Department, University of Glasgow, November 2007, https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/library/files/special/exhibns/month/nov2007.html. Accessed 8 November 2021.

Su, Hongxi. “Revolution Through Poetry.” Willliam Blake and Enlightenment Media, https://williamblakeandenlightenmentmedia.wordpress.com/tag/europe-a-prophecy/. Accessed 10 November 2021.