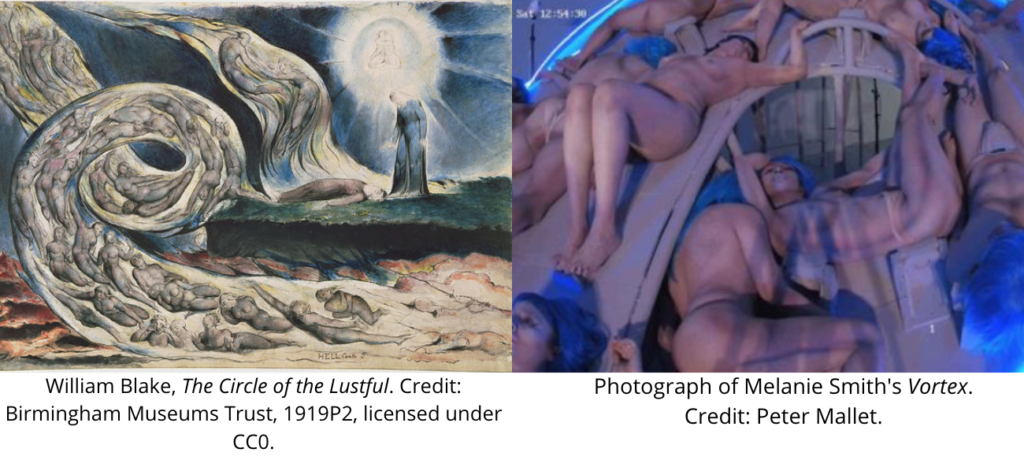

Melanie Smith is one of the leading artists of her generation. Her recent piece Vortex is a multimedia work inspired by William Blake’s The Circle of the Lustful that intertwines performance, sculpture, and moving images. Smith’s installation at the Parafin in London, titled Leave it to the Amateurs, pulls from Vortex, consisting of film, photographs, and collages. These are displayed alongside paintings on panel that are derived from the works of Blake.

This is Smith’s second solo exhibition in London and first with Parafin. Born in the UK in 1965, she moved to Mexico City after graduating from the University of Reading, where she studied painting and post-minimalist aesthetics. While she has played an important role in the art scene of Mexico City, the city itself, as well as Mexico as a whole, has been a huge influence on her work. This can be seen in pieces such as Spiral City (2002) and Aztec Stadium (2010).

Smith is recognized internationally and has exhibited in such institutions as MOMA, the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, the ICA in Boston, and Tate Modern. Writing for Art Nexus in 2018, Ricardo Pohlenz reflected on the multi-dimensional nature of her work:

The work by Melanie Smith relies on images as products of modernity. She explores and demarcates their different substrates to convey their genealogies in the exhibition space. The trick behind her illusions depends on what she chooses to show and to keep hidden, their inherent weight, what is kept vs what is lost. She is interested in sediments—in the sedimentation process, in visual decantation—approached through their multiple gestures, trapped but also freed in film and video, deconstructed until they become abstractions that rely on their processes for signification.

We encourage readers to learn more about Smith’s groundbreaking work by visiting her website and exploring her exhibition at Parafin. Below, in her own words, she explains how Blake has influenced her work, particularly Vortex.

*

Since my experience of living and working in Latin America, I have been considering the history of art through gazes and viewpoints that differ from a westernized perspective. This has been clear in various other film projects where I question abstraction, the monochrome, and more recently – medieval painting. In 2017, I made a multi-faceted performative piece in La Tallera (David Alfara Siquieros’ ex studio), Cuernavaca, Mexico. This performance piece created spatially complex theatrical perspectives, putting the backstage on the front stage whilst making the workplace a continuous exhibit. The space became a studio where carpenters, students, local seamstresses, scenographers and a restoration specialist came together to recreate a mixture of tableaux vivants from Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Brueghel the Elder’s paintings. Over three months, seven live activations from fragments of the original paintings were made with students from the local theatre school and were simultaneously recorded on nine different security cameras. During the activations, musicians played accompanying interpretations, conjoining unfinished fragments and multiple itineraries. This whole process produced a lapsus of bodies and histories while questioning the status of painting and the sequential nature of movement-image.

Like many artists, Blake has been at the back of my mind for a long time. There is something in the sensitivity of his lines and expressions of the human condition that seems particularly relevant to our time. Beyond this current pandemic moment we are passing in history, Blake’s figures seem to be characters that compose all ages – as if they represented the same condition repeated again and again. He depicts constricted and distorted forms of life and spirits that seem to break with the systemization of the rational, drawing them out from his unconscious. From afar, living in Mexico City, I thought of Blake’s interpretation of Dante’s Inferno and how he saw industrial London as a city of hallucination and hell. Blake adapted Dante’s medieval ideas of damnation to his vision of London in an unrepressed state during a time of despair. In turn, I was thinking of parallels in the human condition in contemporary Mexico City. Just at the moment when I was considering spending more time in London, I came to the idea of making a tableau vivant with CCTV cameras, similar to what I had worked on with Bosch and Brueghel.

I decided to work with Blake’s illustration The Circle of the Lustful interpreted for Dante’s Divine Comedy, because of its narrative. The sin of Lust (in Latin luxuria) was listed among the Seven Deadly Sins, which were used by Dante Alighieri to craft his versions of Hell and Purgatory in The Divine Comedy. Lust originally was not only an obsessive desire for sex, but also expensive items and excessive comforts, also defined as an overzealous longing for something or someone. In many ways, Blake’s work becomes a point of departure for ways of expressing or responding to historical layers that become distorted and fragmented through my particular perspective. For example, the motif of the spiral (the central symbol in the illustration), is a constant recurrence in my work. As well as this, the bodies that were used in the performative recreation of the illustration in the form of a tableau vivant are not Blake’s white bodies but mestizo Mexican ones. With six surveillance cameras, and through the use of digital bandwidth including a peephole system, I directed the live-action from one museum space to another. The reactivation of the original was also done with amateurs, that come together through a one-time collaboration into a sort of squashed up but stretched out picture plane through time and distance. I filmed the distance from afar. This “afar” is a metaphorical afar, in as much as the one who directs the action (me in this case) comes from afar, from one could say, a different gaze, or a different time-space. Distance becomes a raw factor in the work, where the cameras zoom in on different details and bodily connections.

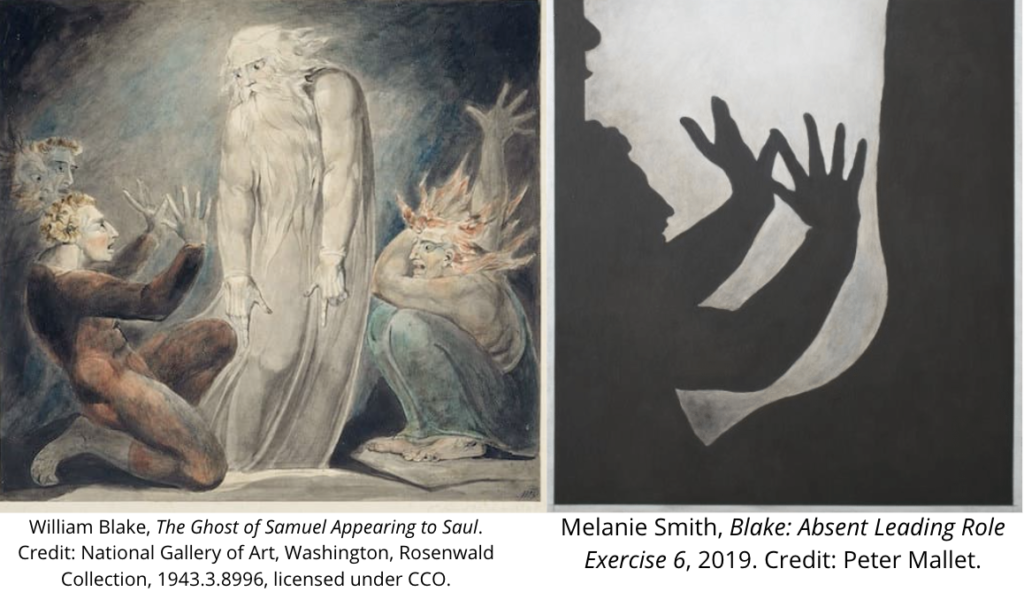

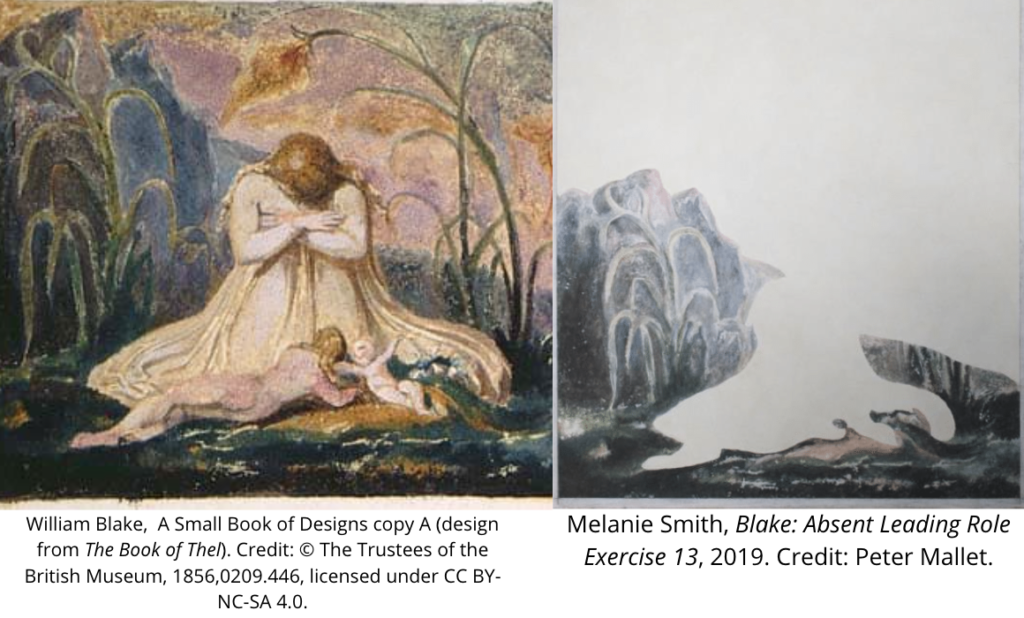

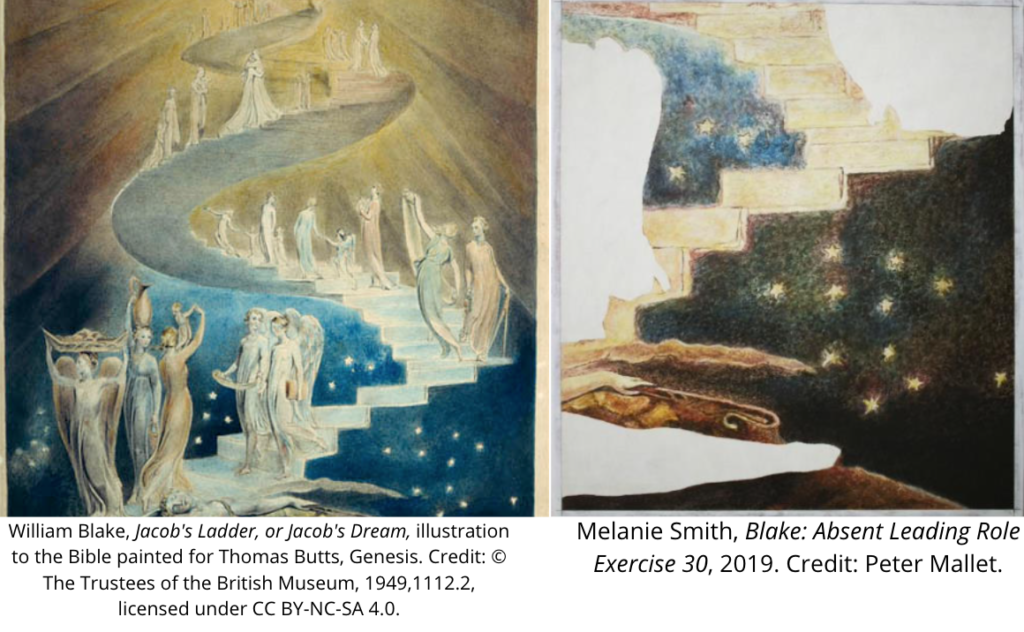

The small paintings that accompany the video are fragments from different Blake illustrations where the lead character has been taken out and left as a blank. In my works, it’s as if the background has become more important than the bodily gestures which are so crucial to Blake’s work. The roles have been reversed and the melodrama of the paintings is presented as a series of abstract scenic backdrops. Blake’s illustration work was never a mere passive visual commentary; he departed from a considerable figurative license through which he advanced his perspectives. In the same way, I propose the stormy composition of Blake as a kind of hallucination of our current condition.—Melanie Smith, 2021

*

We are very grateful to Celia Higson from Parafin and Luisa Calè, the Blake Quarterly exhibitions editor, for making this blog post possible.