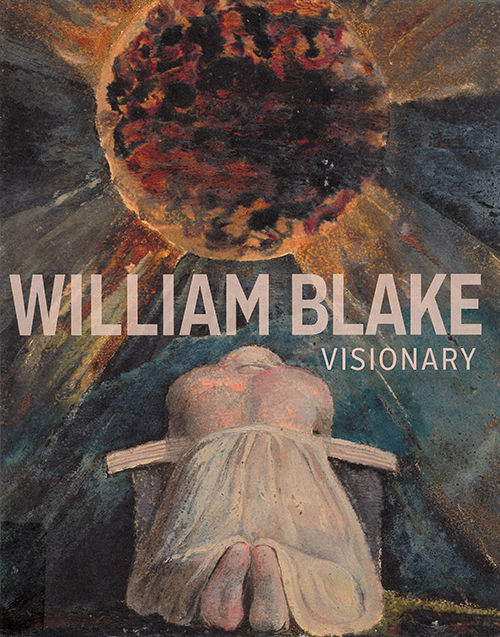

The Tate Blake exhibition closed its doors in February and the many works on display are presumably now all safe and sound at their home institutions. At the Blake Quarterly I’ve been consulting the exhibition catalogue and referring to installation photos in the process of laying out Luisa Calè’s review for our upcoming spring 2020 issue.

As comprehensive as the catalogue and photos are, they don’t reflect the wizardry of the ghost of a flea striding along the facades of houses on Broadwick (formerly Broad) Street in Tate’s promotional trailer or Urizen circumscribing the universe—”The Ancient of Days”—on the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral for four evenings in late November and early December 2019.

We asked Tate’s marketing department about the impetus for and logistics of these ventures. Many thanks to Kathy Maniura, Tate Britain marketing officer, for responding to questions from Luisa and me; to Chris Condron, head of marketing, and Martin Myrone, co-curator of the exhibition, for facilitating the Q&A; and to animation director Sam Gainsborough for permission to post the video of the trailer. The exchange has been edited slightly.

How did your advertising campaign extend the space of the exhibition into the city? What was the strategy behind your animations?

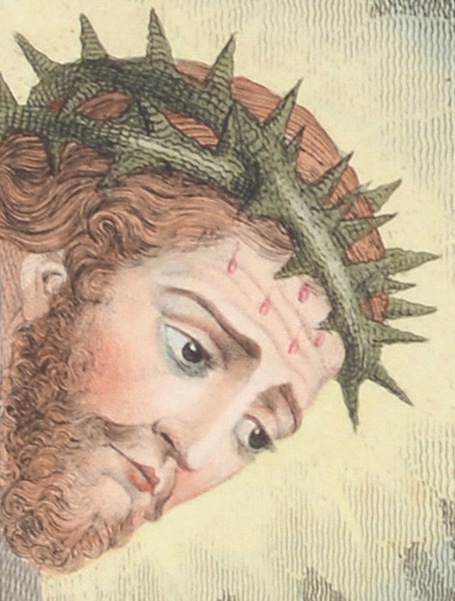

Tate is committed to promoting access to art, including bringing it outside the gallery in a way that feels authentic and appropriate. A key strand of the strategy for our William Blake exhibition was positioning Blake as an iconic Londoner. This, coupled with his desire to see his works on a large scale, meant that projecting his artwork onto such a central London landmark [St. Paul’s] was the perfect way to communicate these messages. It also built on the marketing trailer for the exhibition, which brought Blake artworks to life by animating his famous figures moving through the city towards Tate Britain.

Thus the projection was a natural extension of the overall creative approach. For Blake’s 262nd birthday, we wanted to celebrate the iconic London artist by making one of his dreams a reality and in doing so, making this masterpiece available for all Londoners to enjoy.

Why did you choose St. Paul’s?

St. Paul’s was an important site for Blake—one he referred to in his poetry, a building whose grandeur influenced his religious and historic visual artworks. The ambition of the project was to activate this powerful link, and remind people of Blake’s status as an iconic Londoner by linking him to a central landmark.

How did you go about getting St. Paul’s to collaborate?

We approached the cathedral through a contact with a written proposal that outlined our ambition for the project and Blake’s links to the building. More detail was added following a meeting with their head of visual arts, and the proposal was then circulated for approval from their senior stakeholders. From then on there were regular meetings between teams as the project progressed, with Tate leading on the logistics. Overall it was very collaborative and great to discover such a historic institution so willing to use their space in innovative and engaging ways, working with a variety of partners. The team there were very accommodating and interested in highlighting the link between Blake and the building and discussing the questions this raised.

What is involved in taking artworks outdoors and projecting them on the facade of other buildings in the city?

A huge number of logistical considerations! We needed to work very closely and were in constant contact with the projection company and the council. From an aesthetic point of view, getting an artwork to reproduce faithfully on a difficult surface (in this case a curved, grey dome) required a considerable amount of planning, retouching, and testing. In general the activation itself needed to feel authentic—both in terms of how the artwork is used and where it was displayed. There needs to be a clear reason behind it for it to resonate with the audiences.