The William Blake Archive is pleased to announce the publication of digital editions of Blake’s receipts.

“Commerce is so far from being beneficial to Arts or to Empire that it is destructive of both” (“Public Address”). “Where any view of Money exists Art cannot be carried on.” “Christianity is Art & not Money” (Laocoön). Rail as he might about the destructive force of commerce and money as “The Great Satan,” Blake had to recognize that money is also “the lifes blood of Poor Families” (Laocoön)—and Catherine and William Blake were often a poor family. Blake’s biographer Gilchrist tells the story of Catherine Blake’s way of reminding her husband that money was running out—by putting an empty plate in front of him. One hoped-for effect was money exchanged for goods or services, perhaps paintings, engravings, or drawing lessons—verified by a receipt.

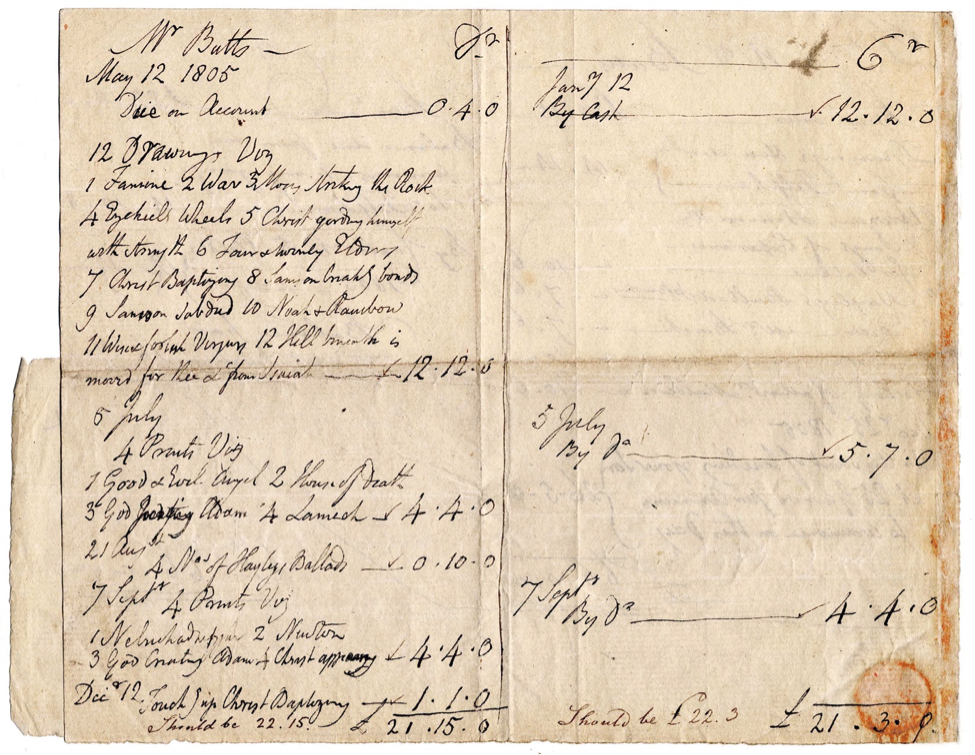

Receipts remind us of bookkeepers and taxes. For most people most of the time, receipts surely fall near the bottom in rank order of interest and importance—until we need one that is missing or discover one that proves something otherwise uncertain or unknown. Their unstable place in the hierarchy of documents makes them rare. They tend to be small, easily overlooked, or discarded when the works they signify move along from place to place, generation to generation. The ones published here are survivors, and most have never been reproduced.

Blake’s receipts often help to establish the first buyer of his works—and the date when a specified amount of money was exchanged for specified objects. Beyond that, the receipts teach lessons in the easily overlooked business side of Blake’s arts and the arts of his era, in which he was a full if frustrated participant. And the documents are often striking. There are beautiful receipts in formal words, numbers, and symbols precisely inscribed in fancy handwriting, decorated with colorful seals that certify the transactions. Equally eye catching, there are scrawled, scratchy composites that are simply fascinating to look at. And there are, of course, plain, practical lists laid out more or less neatly in columns.

In our treatment of the receipts, we are departing from the editorial principles favored by earlier editors: Geoffrey Keynes mixed receipts and letters in a single chronologically ordered category; David V. Erdman largely excluded them; G. E. Bentley, Jr., excluded them from his edition of William Blake’s Writings and moved them into an elaborate appendix to Blake Records that attempts to cover a broad range of transactions from multiple angles—including, for example, the receipts generated by Blake’s customer, promoter, and friend John Linnell, a careful keeper of accounts, in the course of producing Blake’s engraved Illustrations of the Book of Job (22 plates, 1823-26). Bentley assembled Linnell’s payments to Blake but also to dealers in copper, “french paper” and “Drawing paper,” in specialized printing for engravings, and cloth bindings, among other products and services (BR 2nd ed., appendix 3, “Blake’s Accounts”).

We have decided instead to publish the receipts in adjacent but separate categories to focus attention on a distinctive commercial genre with some striking historical features. But the border between receipts and letters is porous because Blake’s financial and personal dealings are entwined. As he embeds poems in his letters, complicating distinctions between them, he similarly personalizes sterile lists of products and prices with greetings, inquiries, and news. And sometimes what we label a receipt is strictly not—but rather, say, a formal contract to carry out a project on specified terms, such as the 25 March 1823 “Memorandum of Agreement” to engrave the drawings that would be published as Illustrations of the Book of Job—on copper plates that would be provided by Linnell. The agreement is in Linnell’s hand, with signatures by both men. Deciding how to treat documents that defy the rules of our rigid categories is one of the questionable pleasures of editing.

Special thanks to the City of Westminster Archives Center for their courteous assistance, excellent digital images, and willingness to share Kerrison Preston’s Blake library with the world.

As always, the William Blake Archive is a free site, imposing no access restrictions and charging no subscription fees. The site is made possible by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with the University of Rochester, the continuing support of the Library of Congress, and the cooperation of the international array of libraries and museums that have generously given us permission to reproduce works from their collections in the Archive.

Morris Eaves, Robert N. Essick, and Joseph Viscomi, editors

Joseph Fletcher, managing editor, Michael Fox, assistant editor

The William Blake Archive