I am far from the first to point out the parallels between Stettheimer and Blake. When the Museum of Modern Art mounted the first retrospective exhibition of Stettheimer’s work in 1946, art critic Henry McBride explained her lack of mainstream, popular success as analogous to Blake’s:

Now what pleases the ‘discerning few’ can please the general if the general be given a chance at it. In art, as in religion, the public finally arrives at the true values. […] At a time when no one else in England thought much of William Blake, Charles Lamb said: ‘But there really is something great in ‘Tiger, tiger burning bright.’’ The six people […] who believed in Blake have all had followers. The first step in the process of acquiring fame is to obtain the six believers. These Florine Stettheimer had. We will shortly be able to estimate their leavening power.

McBride invokes Blake to show that though many of his contemporaries may not have understood or appreciated his expressive, visionary work, Blake has received posthumous fame. McBride suggests that only after Blake’s death could his work enjoy the critical acclaim it deserves; likewise, Stettheimer never garnered widespread attention during her life, but her spirited and original style will earn their due praise.

In spite of McBride’s predictions, Stettheimer remained relatively obscure in the public art world until second-wave feminism inspired many art scholars to revive the overlooked work of women artists. Linda Nochlin, who famously penned “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” in 1971, wrote an article that highlights Stettheimer’s ability to reconcile confectionary, decorative tropes with keen social insight, thereby constructing an early camp sensibility. Nochlin demonstrates Stettheimer’s tact in drawing from art-historical precedents, including William Blake:

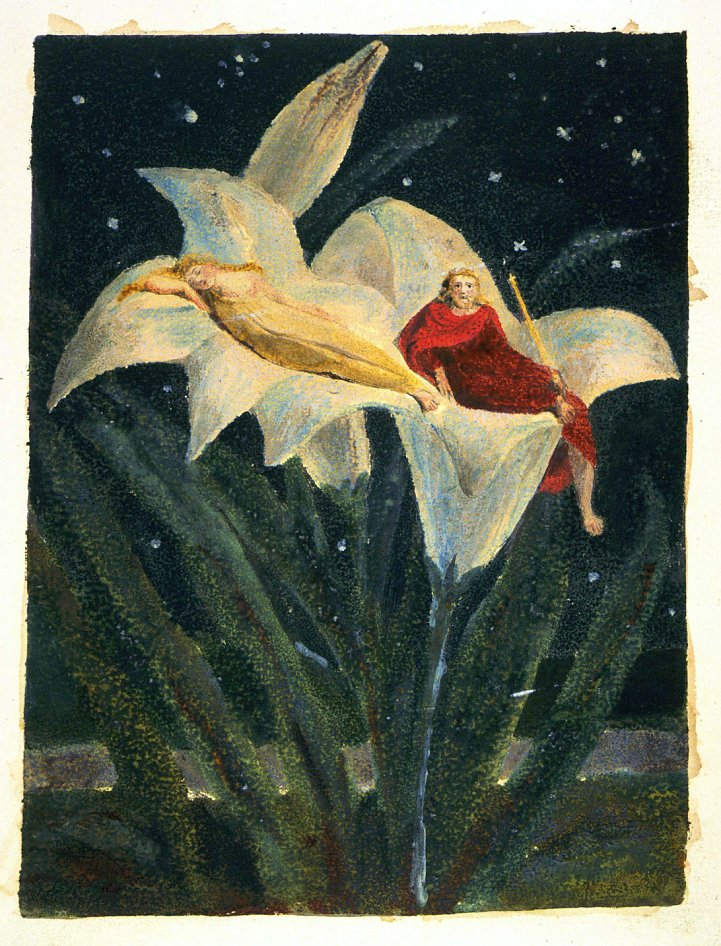

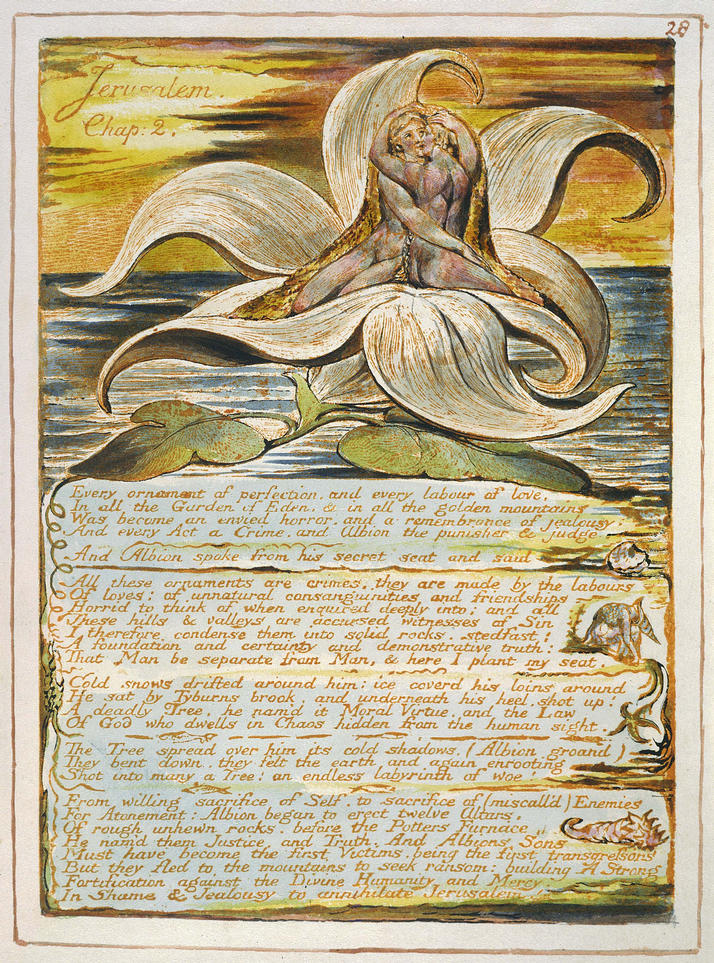

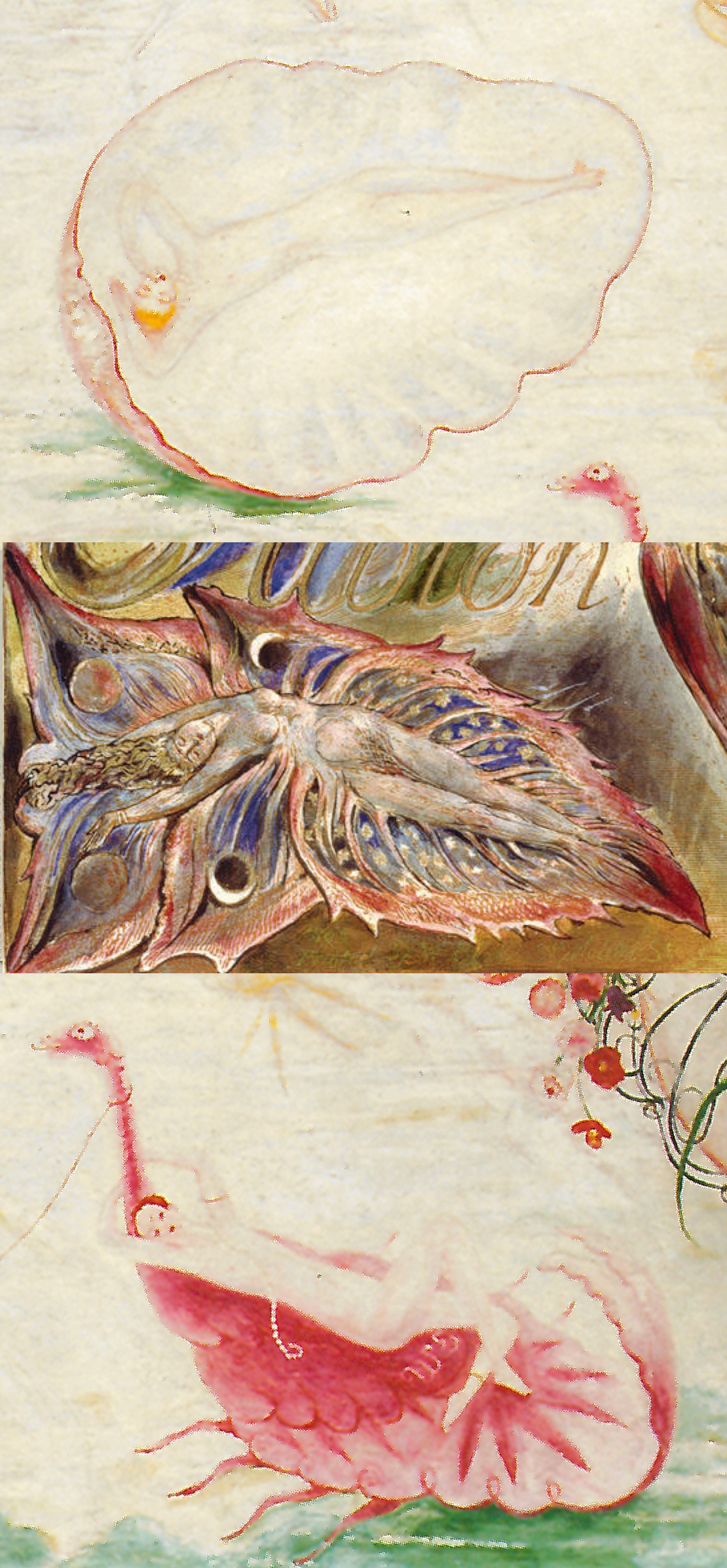

Often, just when we think she is being her most naïvely ‘uninfluenced,’ Stettheimer is in fact translating some recherché source into her own idiom. Such is the case with the Portrait of Myself of 1923, which draws upon the eccentric and visionary art of William Blake, whose reversal of natural scale, androgynous figure style and intensified drawing seem to have stirred a responsive chord in Stettheimer’s imagination. Blake’s illustration for his Song of Los, with the figure reclining weightlessly on a flower, seems to have been the prototype for Stettheimer’s memorable self-portrait, and indeed it had been published in Laurence Binyon’s Drawings and Engravings of William Blake in 1922.

Nochlin’s comparison is apt. Though determining Stettheimer’s intention is tricky at best, the stylistic similarities between Portrait of Myself and the fifth plate of Song of Los are visually apparent. Both works show slender, curvilinear human bodies draped over flower-like objects in languor. Both feature bright red figures against textural, painterly, creamy white grounds.

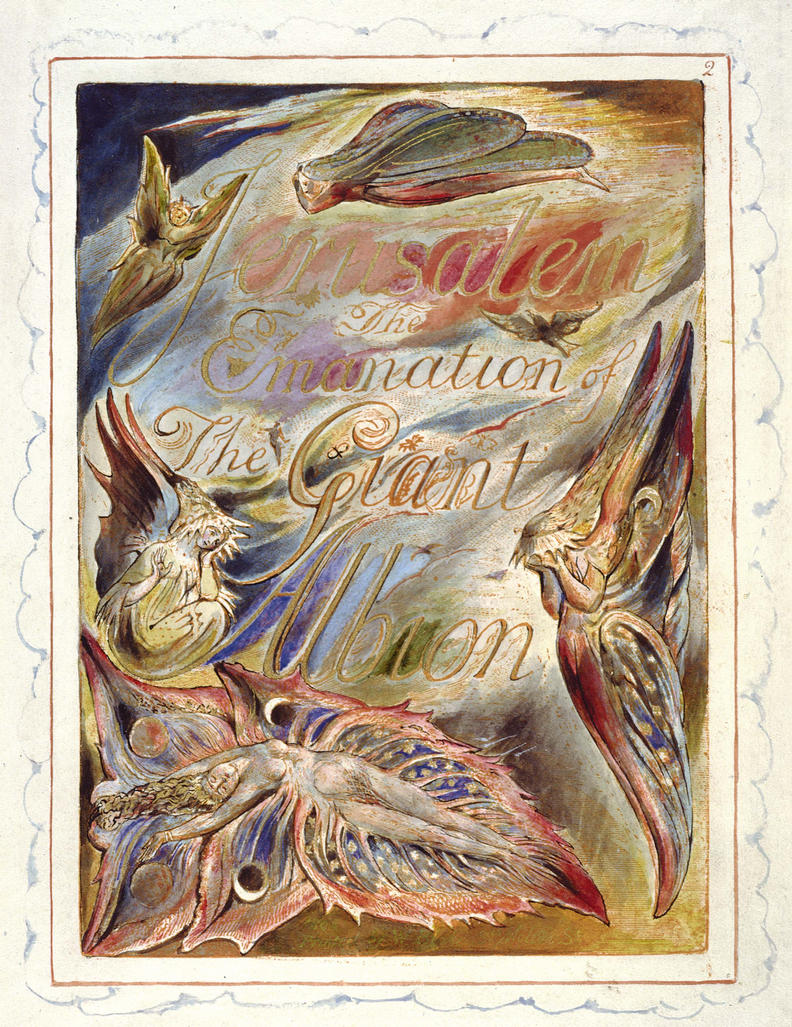

Nochlin’s observation has inspired other scholars to draw similar comparisons. Jui-Ch’i Liu cites Nochlin before arguing Portrait of Myself “is closer to the famous illustrated drawings of the androgynous reunion of the male hero Albion and his female emanation Jerusalem in Blake’s final epic Jerusalem.” She continues: “Stettheimer’s interest in artifice, however, makes her transfigure the lily in Blake’s drawings into a red flower-like couch, and the modeling and draughtsmanship into a flat and decorative body, costume, and ornaments.”

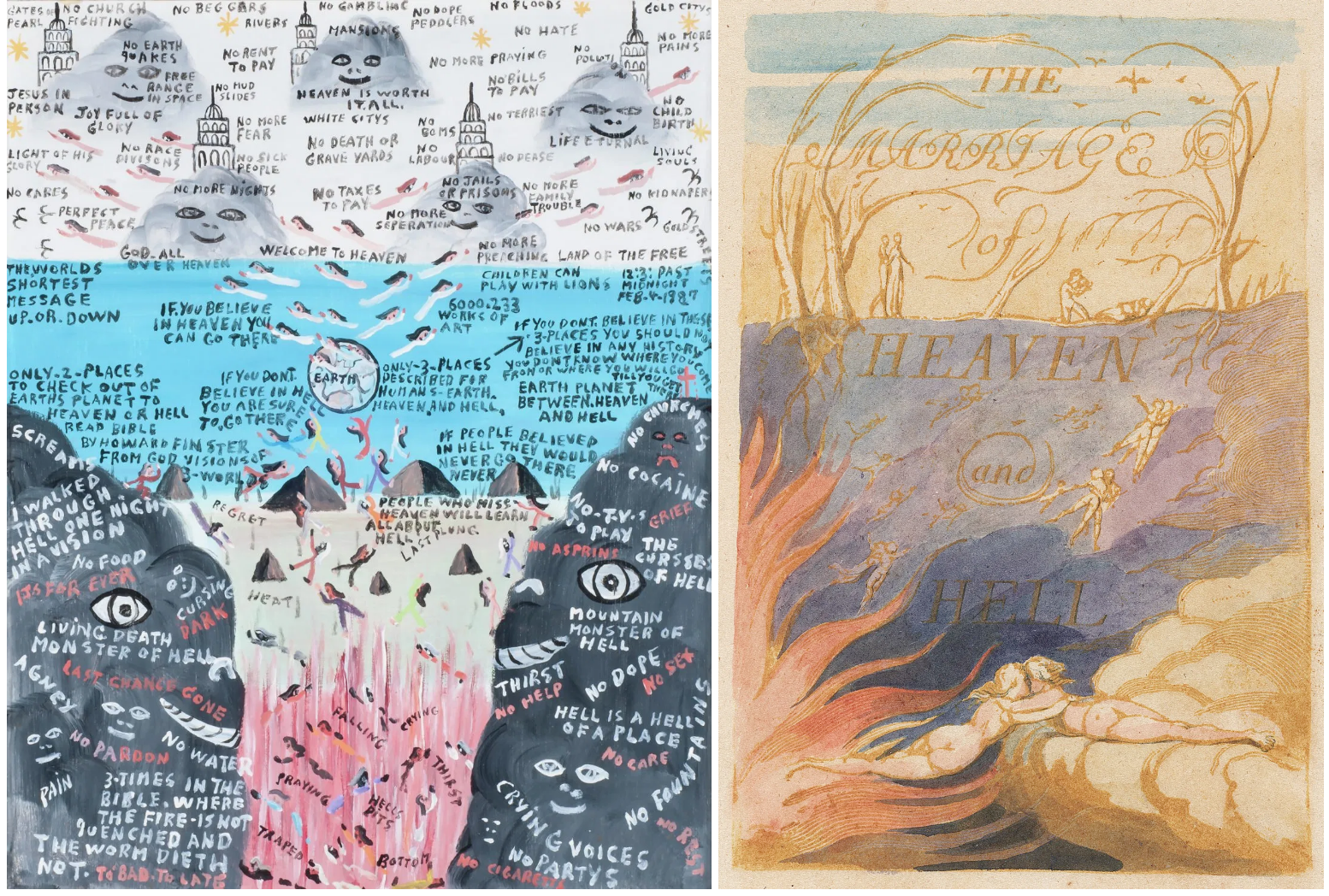

The comparisons that Liu and Nochlin forward are generative, and I aim to build upon their claims by adding further Blakean parallels to the conversation. Portrait of Myself also recalls the reclining figure surrounded by flames in Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Both Stettheimer’s and Blake’s figures appear androgynous and almost nude if not for their shrouds of pinkish, diaphanous washes of pigment. The two are surrounded by bright, warm, red, feathered shapes—though Blake’s figure is engulfed in flames, Stettheimer’s furniture has its own flame-like appearance. Compositionally, Stettheimer’s portrait is reminiscent of Blake’s illustration, “Dante and Statius Sleeping with Virgil Watching.” Both works have recumbent humans in the lower left corner of the support, held in tension with a circular, ring-like sun in the upper right corner. Both suns have stratified, triangular rays.

“Dante and Statius Sleeping with Virgil Watching.” Illustrations to Dante’s Comedy, Copy 1, Object 89, 1824-27. Pen and ink and water colors over pencil, 52.0 x 36.8 cm. Ashmolean Museum.

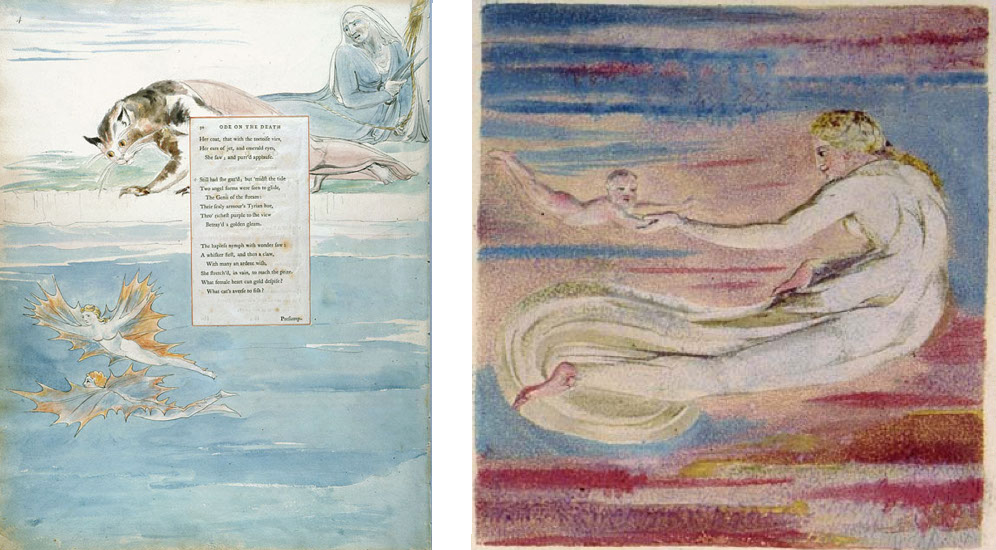

Stettheimer’s self-portrait is not the only work of hers to draw from Blake’s oeuvre. In general, the two share in their pastel-yet-acidic, candy-coated-yet-haunted color palettes, their depictions of elongated human bodies, their irregular and artifice-laden rendering of scale, their usage of negative space, their inclusion of morphing, hybrid creatures, and their treatment of textual elements as part of the pictorial composition. Using the William Blake Archive, I found many provocative points of visual connection that I cannot analyze at length in the scope of this post. Still, I want to share some illustrations of the iconographic and stylistic recurrences between Blake and Stettheimer because of the curiosity, wonder, and exploration they invite.

The following images show how Stettheimer and Blake employ disproportionally large fields of negative space surrounding their figures. The negative space enables the artists to punctuate their compositions with rhythmic curvilinear forms. Note how both Stettheimer and Blake use faint lines radiating from their figures, giving them a glowing, supernatural quality.

“The Argument.” Visions of the Daughters of Albion, Copy A, Object 2, 1793. Relief etching, 14.2 x 11.2 cm. The British Museum.

Stettheimer and Blake favor wispy, thin, tall branches and winding, vine-like flora as framing devices. Trees and tall floral arrangements constitute major vertical lines in the works; curving branches form arches, vaults, and architectural features to frame the artists’ subjects, which are often disproportionate in scale to the boughs, stems, and petals.

America a Prophecy, Copy O, Object 9, 1821. Relief etching and hand coloring, 23.5 x 16.8 cm. Fitzwilliam Museum.

“The Book of Thel, Plate 2.” A Small Book of Designs, Copy A, Object 10, 1796. Relief etching with color printing and additional water colors and pen and ink outlining. 8.2 x 10.6 cm. The British Museum.

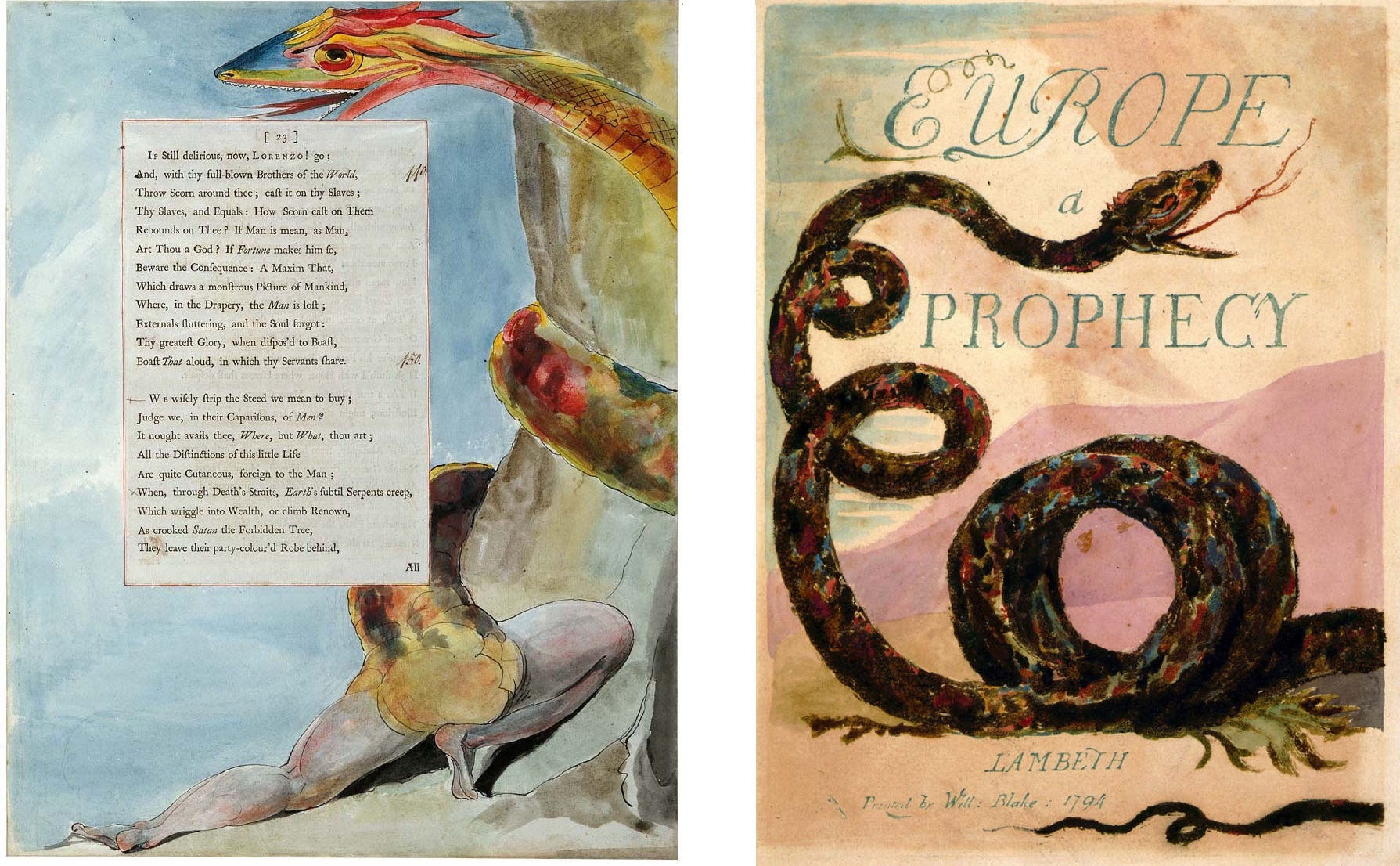

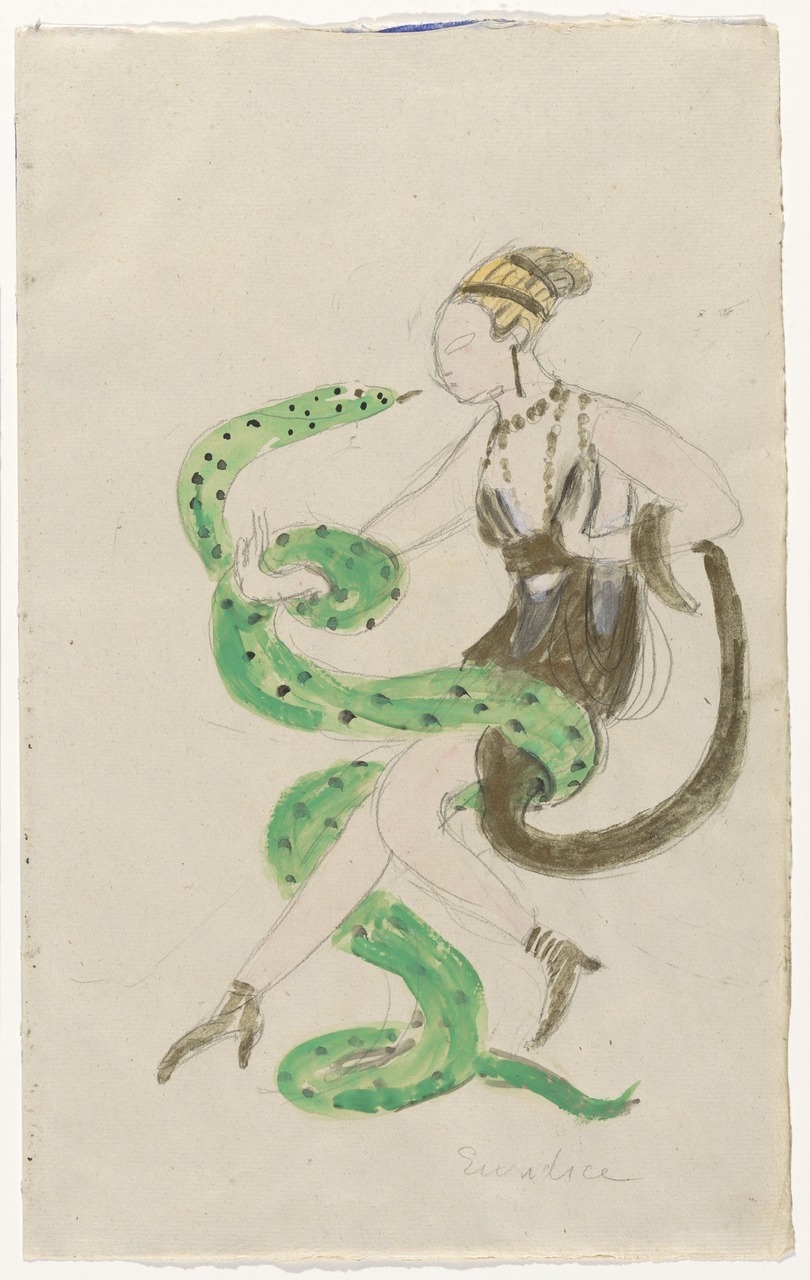

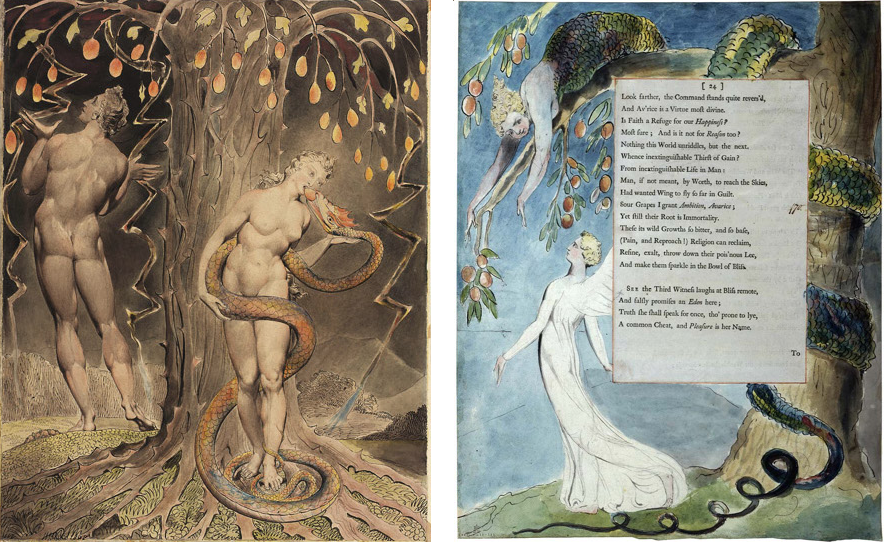

Many of these vertical structures, for both Stettheimer and Blake, have snakes wrapped around them. Snakes are universal subjects of artistic figuration, but Stettheimer and Blake include snakes frequently and stylize the reptiles with a certain vibrant animation. Note the typography in and around the snakes’ bodies in the following two Stettheimer paintings, which exemplify one of the many experimental and unusual ways she incorporates language into her pictorial work.

“Moses Erecting the Brazen Serpent.” Water Color Drawings Illustrating the Bible, Object 11, c. 1801-02. 34.0 x 32.5 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Europe A Prophecy, Copy E, Object 2, 1794. Relief and white-line etching with color printing and hand coloring, 23.9 x 17.3 cm. Library of Congress.

Stettheimer and Blake entangle their snakes with women—namely, Eurydice and Eve. Again, these topics are common in canonical Western art, but these two artists’ interpretations have striking resonance.

“Night VII, page 24.” Illustrations to Edward Young’s ‘Night Thoughts’, Copy 1, Object 296, c. 1795-97. 42.0 x 32.5 cm.

“Eve Tempted by the Serpent.” Paintings Illustrating the Bible, Object 1, c. 1799-1800. Tempera, 27.3 x 38.5 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum.

Metamorphosing, hybrid beings and acrobatic figures float, glide, and fly through space in these artists’ compositions. Women’s bodies blend into giant shells and enormous moths, or lounge on top of swan-crab-fish amalgamations.

“The First Book of Urizen, Plate 2.” A Small Book of Designs, Copy A, Object 12, 1796. Relief etching with color printing and additional water colors, pen and ink outlining, 11.1 x 10.3 cm. The British Museum.

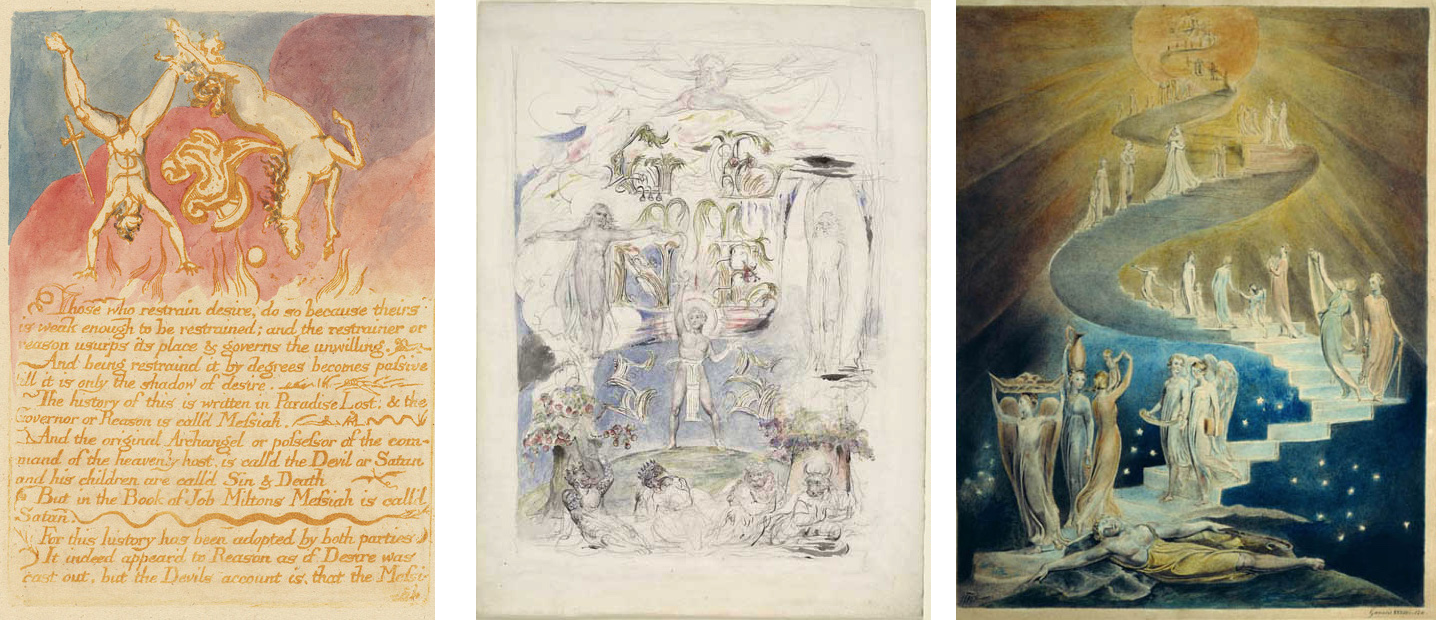

The two artists emphasize centrality in their composition, which pairs with their specific mobilizations of negative space. Fantastical structures, mixed scales, and compression of the pictorial plane create an otherworldly environment where text and image commingle.

Genesis, Copy 1, Object 2, 1827. Pencil, pen and ink, water color, and shell gold, 37.9 x 27.9 cm. Huntington Library.

“Jacob’s Dream,” Water Color Drawings Illustrating the Bible, Object 4, c. 1807. 37.0 x 29.2 cm. The British Museum.

Bibliography

Brown, Stephen, and Georgiana Uhlyarik. Florine Stettheimer: Painting Poetry. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2017.

Gammel, Irene, and Suzanne Zelazo. “Wrapped in Cellophane: Florine Stettheimer’s Visual Poetics.” Woman’s Art Journal 32, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2011): 14-21.

Liu, Jui-Ch’i. “Carnival Culture and the Engendering of Florine Stettheimer.” Ph.D. diss., Bryn Mawr College, 1999.

McBride, Henry. Florine Stettheimer. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1946.

Nochlin, Linda. “Florine Stettheimer: Rococo Subversive.” Art in America, September 1, 1980.

Sussman, Elisabeth, and Barbara J. Bloemink. Florine Stettheimer: Manhattan Fantastica. New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, 1995.

Tyler, Parker. Florine Stettheimer: A Life in Art. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Company, 1963.