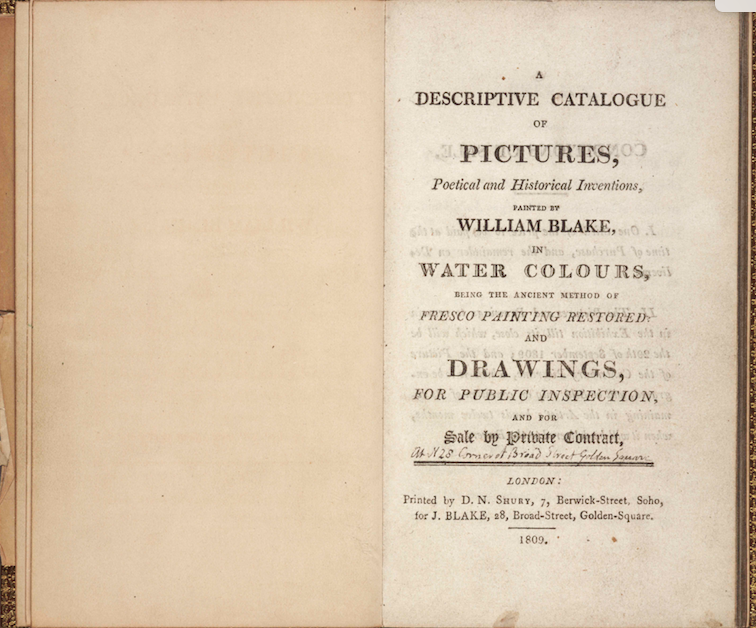

The William Blake Archive is pleased to announce the publication of A Descriptive Catalogue of Pictures, Poetical and Historical Inventions, Painted by William Blake, in Water Colours, Being the Ancient Method of Fresco Painting Restored: and [water color] Drawings, For Public Inspection, and for Sale by Private Contract. Printed by a job printer in a small run, perhaps fewer than one hundred copies, the catalogue accompanied his self-organized one-man exhibition of 1809-10. It hung in the rooms above his brother’s haberdashery shop in Soho—Blake’s childhood home. The price of the catalogue included admission to the exhibition.

British artists spent much of the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries struggling to find viable commercial outlets. Lamenting that they lacked the infrastructure of patronage, exhibition, and refined understanding that supported Continental artists, they promoted the formation of new institutions, such as the Royal Academy and the British Institution, to add gravity and legitimacy to match commercial opportunity. Commercial gallery schemes such as Boydell’s Shakspeare Gallery were popular if unsuccessful marketing experiments. Diverse individual and group exhibitions, both fixed and traveling, were attempted in locales from Green Park to the Royal Academy to the homes of individual artists, such as J. M. W. Turner, who devoted domestic space to the exhibition of their work. Descriptive catalogues and other printed documentation were a regular part of these innovations in art marketing.

Blake’s catalogue describes sixteen pictures, nine in his version of “portable fresco” (gum- or glue-based tempera), seven in water color—several of those borrowed from his patron Thomas Butts. The exhibition was anchored by two of the temperas, Sir Jeffery Chaucer and the Nine and Twenty Pilgrims on Their Journey to Canterbury—described perceptively in considerable detail and afterwards engraved—and The Ancient Britons, by far the largest painting Blake ever executed. It and four others are now lost.

Henry Crabb Robinson later characterized Blake’s catalogue as a “veritable folio of fragmentary utterances on art and religion, without plan or arrangement” (Blake Records page 450). Rhetorically, it is a high decibel, cacophonous, aggressive amalgam of painting by painting descriptions punctuated with strong statements of artistic principle colored by enthusiasm, resentment, blame, and defensiveness, sharpened by hints of conspiracy, technical description, and assorted other forays, often within a single entry. Blake makes his usual appeal “to the Public”—the authentic, idealized public in which he consistently claims to have faith—as a refuge from the villains of commerce, politics, and bad art.

It is easy to see why Robert (brother of Leigh) Hunt, the only reviewer, charged Blake, “an unfortunate lunatic,” with having produced “a farrago of nonsense, unintelligibleness, and egregious vanity, the wild effusions of a distempered brain” (The Examiner 17 Sept. 1809, Blake Records page 283). But Charles Lamb, tolerant of eccentricity, was “delighted” with the catalogue, according to Crabb Robinson (Blake Records page 694). Of course, the crusade that Blake attempted to launch with his exhibition was in one sense mad—or at least hopelessly quixotic, yet another dismal failure to secure recognition, respect, and income. We have no attendance records, but what slender evidence there is suggests that the exhibition and catalogue attracted little other than sufficient public mockery and scorn to wound and infuriate Blake once again.

But, more broadly, the exhibition signaled a pivot from the battered hopes of an inventive youth and middle age—years when Blake was often able to claim some of Britain’s best artists as supporters, despite a string of major disappointments—into his last two decades, ultimately brightened by the appearance of a new generation of artistically sympathetic young admirers and sponsors. The catalogue and the exhibition it registers are products of new, or renewed, artistic ideas and projects, bolstered by a determination to crusade openly for the reformation of British art—to eliminate its commercialism and return (as Blake imagined it) to older, purer, original forms of expression represented by Michelangelo and Raphael, who he thought united conception and execution in coherent lines lost by modern British oil portraitists such as Joshua Reynolds, whose elaborate effects of tone and color were mere pretty, superficial distractions from the impoverished, incoherent—in Blake’s lexicon, blurred and blotted—visions beneath them. The 1809 exhibition and catalogue aim to call Reynolds’s bluff, as it were, by showing modern artists and audiences how to shed the hypocrisies of blotting and blurring and return to the truth of vision expressed in media, such as “the Ancient Method of Fresco Painting Restored,” that could bear the weight of truth.

As always, the William Blake Archive is a free site, imposing no access restrictions and charging no subscription fees. The site is made possible by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with the University of Rochester, the continuing support of the Library of Congress, and the cooperation of the international array of libraries and museums that have generously given us permission to reproduce works from their collections in the Archive.

Morris Eaves, Robert N. Essick, and Joseph Viscomi, editors

Joseph Fletcher, managing editor, Michael Fox, assistant editor

The William Blake Archive