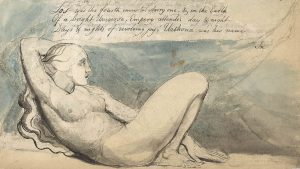

The William Blake Archive is pleased to announce the publication of a digital edition of Blake’s VALA, or The Four Zoas. This edition is based on fresh digital photography from the British Library and is presented in Preview mode—with enlargements and basic bibliographical information but without transcriptions or illustration descriptions.

The messy, complex manuscript of nearly 150 pages that has slowly settled into Blake’s oeuvre under its odd double name has resisted efforts to edit it satisfactorily in print, but for those who aim to grasp the full compass of Blake’s artistic, social, and spiritual aspirations, the manuscript is indispensable. Northrop Frye wrote that “There is nothing like the colossal explosion of creative power in the Ninth Night of The Four Zoas anywhere else in English poetry,” while the work as a whole is “the greatest abortive masterpiece in English literature” (Fearful Symmetry page 305). Indeed, there is that—but there is also, as Frye recognized, the pivotal place of VALA, or The Four Zoas in Blake’s creative life as writer and visual artist.

It may seem odd, then, that most of the nineteenth century managed to overlook it. In “The System,” volume 1 of Edwin John Ellis and William Butler Yeats’ very ambitious three volumes of interpretation, paraphrase, selected lithographic reproductions, and edition of Blake’s works published in 1893, they scolded their predecessors: “But though whatever is accessible to us now was accessible to them when they wrote, including the then unpublished ‘VALA,’ not one chapter, not one clear paragraph about the myth of Four Zoas, is to be found in all that they have published” (volume 1 page viii). They are pointing to Alexander Gilchrist and his collaborators, who had produced the landmark Life of William Blake, “Pictor Ignotus” thirty years earlier in the first attempt to piece together the scattered bits of Blake’s life: a birth-to-death narrative plus several supplements, including reproductions, extracts, and William Michael Rossetti’s lists—the first of their kind—of a considerable range of Blake’s life’s work. Their aim had been to bring into focus a William Blake who, in the years since his death in 1827, had been inexorably dispersing into incoherent filaments that, without strong intervention, would have become irrecoverable. Gilchrist and company had been remarkably successful in assembling a multi-dimensional, concretely memorable representation of Blake.

Without it, in fact, Ellis and Yeats would never have been able to launch their own massive project three decades later. But they were right about the Four Zoas, which for them was both a central document, VALA, and the central idea in their elaborate interpretation of Blake. How had it come into being and then disappeared for so long?

In c. 1794-95 Blake secured a commission to produce engraved illustrations for a deluxe new edition of Edward Young’s popular long poem, The Complaint: or, Night-Thoughts on Life, Death, & Immortality, structured as nine “nights.” Blake worked very hard on this commercial project, the largest of his life, producing over 500 large preliminary watercolors and over 40 engravings for the first and only published volume (1797) before the four-volume project was discontinued.

Out of this intense and undoubtedly disappointing episode emerged one of Blake’s most formidable creative efforts—a long narrative of nine “nights,” on paper and proofs of the Night Thoughts engravings left over from the Edwards venture. VALA, or The Four Zoas is epic and cosmic in scope, an attempt to explain the human situation—and to offer a vision of redemption based on a kind of corrected Christianity that requires a complex retelling of the mental, physical, and spiritual history of the world, one that, as Blake later put it, reads the Bible white where others read black—“a cyclic vision of life from the Fall to the Last Judgment . . . . in a single form the totality of what Blake came into the world to say” (Frye page 269).

The illuminated books of the 1790s had been, in effect, installments in this eventual monomyth, and VALA seems to have become the artistic workshop in which the myth could be fully imagined. Having begun with confidence—part of the manuscript is clean fair copy in an elegant copperplate hand—Blake at some point began drafting and revising in several stages. Night the Ninth is titled “The Last Judgment,” which is about as finished as one can imagine, but there are two nights numbered seven, many indecisive revisions, sketches of various sorts, and other features that indicate an unfinished, ultimately abandoned project that had at least served to lay the foundations for Blake’s largest illuminated books by far, Milton a Poem and Jerusalem, all narrated, like The Four Zoas, in unrhymed heroic fourteeners, the seven-stress line that Blake had begun mastering in the 1790s. The Zoas manuscript seems to have been put aside about 1807 after nearly a decade of off and on work, including the three years that Blake spent in Felpham.

Before he died, Blake gave the manuscript to his fellow artist, friend, and patron John Linnell, and it remained in the family until 1918. Ellis and Yeats borrowed it from Linnell’s sons and went to work trying to sort out the scrambled pages and untangle the mass of revisions so that they could present, in their third volume, a selection of crude lithographic reproductions and a complete (though unreliable) printed edition, with notes, under the title VALA, cited many times in the two preceding volumes of commentary and paraphrase that attempt to build a structure of meaning centered on the myth of the Zoas. This is remarkable because, as they themselves said, this “prophetic” side of Blake’s oeuvre had been discounted and timidly represented.

As a poet, Blake had been known almost entirely through the texts extracted from his Songs of Innocence and of Experience. This began to change with the publication of Gilchrist’s Life, governed by contradictory impulses toward comprehensive coherence on the one hand and normalization on the other to produce a paradigm of the imaginative artist who was not, however, insane. Remarkably, until Ellis and Yeats published their edition in the final decade of the century, it was mentioned in print only twice, both times dismissively—first in William Michael Rossetti’s list of works by Blake (Gilchrist 1863, volume 2, page [240]; second edition, 1880, volume 2, page 256) and again in the Prefatory Memoir to his Aldine edition (page cxxx). As Rossetti had put it, “With the exception of this very extraordinary—. . . and very unreadable—series of works”—he means Blake’s “prophecies”—“our edition presents the whole body of Blake’s poetry” (page cxxx). That next bold move—taking the “exception” from periphery to center to radically realign “the body of Blake’s poetry”—required Ellis and Yeats, whose spiritual investments attracted them especially to those very works.

The Archive now contains 143 fully searchable and scalable electronic editions of important manuscripts and series of engravings, color printed drawings, tempera paintings, water color drawings, including 105 copies of Blake’s nineteen illuminated books—all in the context of full bibliographic information about each work, careful diplomatic transcriptions of all texts, detailed descriptions of all images, and extensive bibliographies.

The Archive has many sophisticated features. We ourselves discover new ways of exploring the Archive almost every time we use it. We are attempting to come to the aid of puzzled users with a series of very short, to-the-point videos on YouTube. Though for the moment there are only a few, soon there will be many. We hope you will take a look:

As always, the William Blake Archive is a free site, imposing no access restrictions and charging no subscription fees. The site is made possible by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with the University of Rochester, the continuing support of the Library of Congress, and the cooperation of the international array of libraries and museums that have generously given us permission to reproduce works from their collections in the Archive.

Morris Eaves, Robert N. Essick, and Joseph Viscomi, editors

Joseph Fletcher, managing editor, Michael Fox, assistant editor

The William Blake Archive

Hello, my name is Yaron Asher , from Israel. I am very fond of William Blake’s works and especially Vala, or The Four Zoas. I would like to ask something that got my eyes in a very profound way: was Blake intended to write parts of the Aramaic phrase taken from the Book of Daniel, which tells the story of Bellshazar’s Feast, Meneh Meneh Tekel Upharsin, on Object 51 (Bentley 209.51)?

Thanks, Yaron.