The Oxford comma is having its moment in the spotlight in recent news, after it was used to clinch a legal case in favor of the five drivers in O’Connor v. Oakhurst Dairy who, according to the interpretation of policy in the absence of the comma, were therefore found to be eligible for overtime pay. And grammar geeks on the side of the Oxford comma have been rejoicing.

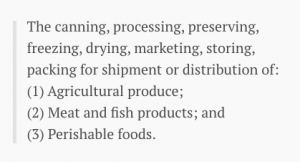

The policy in question in the Oakhurst Dairy case.

But what the Oxford comma news provides is an example of how the simplest punctuation can completely change an interpretation of a statement, something not only grammar geeks have known for a long time, but especially recognized by literary scholars and those of us at the William Blake Archive working with the digital transcription of Blake’s illuminated texts and manuscripts. Is that a comma, or a period? An apostrophe, or a random mark on the material of the paper?

Currently, as an editorial assistant with the William Blake Archive, I aid with checking spelling and spelling errors in digitized issues of Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly. I will occasionally come across alternative spellings that appear in the figure transcription of an image in the digitized issue brought in from the William Blake Archive. It is always a reminder of my earlier duties when I helped with image markup and transcription. I remember an occasion where a group of editorial assistants, working with Blake Archive Team South (BATS) at UNC Chapel Hill, surrounded the workstation of former assistant Sarah Shaw, to see if we could help her figure out an answer to her question about transcribing a punctuation mark: “Is that a comma, or a period?”

Revisiting this editorial work we do at the archive inspired a conversation with Joe Viscomi about the editorial principles used in work with Blake. What we do at the archive in transcribing Blake’s text from the “source” is to create a diplomatic text, a text which corresponds accurately to how the text is presented in one copy—and one copy only. This serves a different purpose from the two major Blake reference texts: Sir Geoffrey Keynes provides a reading text, wherein the editorial principle is to silently “clean up” the text to make it easier for reading, whereas David Erdman’s text is an eclectic text, or an ideal text, which is closer to Blake’s actual text in that it takes the “average” of the multiple copies of a work to make editorial decisions for the transcription. At the archive, we make a decision on whether a mark is a comma or a period based on how the mark looks in a particular copy of a particular work, and not how it functions. If the mark has a tail, for example, we transcribe it as a comma rather than as a period, whether it is grammatically correct or not.

In our diplomatic transcriptions at the archive, then, we make the call, but the beauty of the archive is that readers and users are able to check the image as well, and if they disagree, they can check for themselves. If a reader wants to challenge or contest a comma–or any of the punctuation marks we transcribe–that clearly makes no grammatical sense, they can do so, much in the way that lawyers challenged the meaning of a policy by noting that a comma was missing. This is something that all readers of Blake encounter, and we here at the archive give readers the opportunity to see this first hand—the presence or absence of punctuation, and how that can change the meaning of the text. It is another tool we hope to provide readers to be able to pursue interpretive questions if they choose.

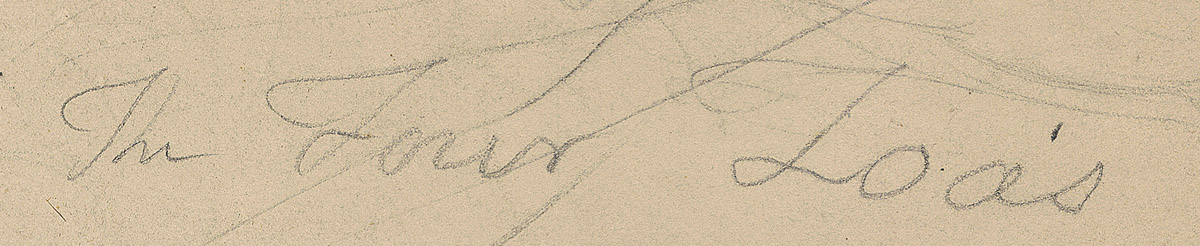

As a case in point in our very own Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly: an article by Justin Van Kleeck on “Blake’s Four…‘Zoa’s’?” in Vol. 39, issue 1, leading to a series of discussion posts in Vol. 39, issue 4 (2006) [see here and here], in which a debate is held about a perceived apostrophe that may or may not appear in the title of The Four Zoa[’]s and the interpretative changes that occur from that possibility.

It reminds me that editorial work in transcription in digital projects are most productive when in dialogue with the scholarly research that approaches the same questions about textual interpretation—that editorial work so often can itself be interpretive, evaluative work with implications both for humanities scholarship and the world outside of academe. To pay attention to something so seemingly small as an Oxford comma, or a rogue apostrophe, reflects on the work many of us do as humanities scholars, who understand the care with which language can be nuanced.

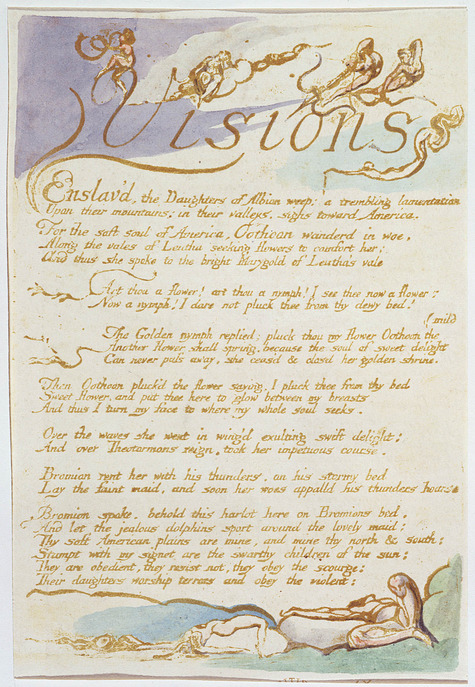

Visions of the Daughters of Albion, copy A, object 3, from The William Blake Archive.

Hello,

Is there an edition of Blake’s writings (print or web) without any punctuation at all?