This semester we’re looking at some of the unique features of the Blake marginalia, and some of the challenges of representing them accurately with TEI elements. One element we’re considering is <metamark>. But what exactly is a metamark?

This is how it’s described on the main website, which is frequently repeated elsewhere online:

<metamark> contains or describes any kind of graphic or written signal within a document the function of which is to determine how it should be read rather than forming part of the actual content of the document.

Note the extreme ambiguity of this description, e.g. about what the ‘it’ actually means. The metamark is a graphic or signal which is supposed to determine how it should be read — ‘it’, meaning of course not the metamark but the document, in which you find the metamark. Not that this brief description gives any indication as to what limits or bounds that ‘document’ or what kind of scope it has for telling the reader how this document (the paragraph, the page, the chapter?) should be read.

And what are we to make of the comment that this mark is not ‘part of the actual content’? Consider what kind of graphics we’re talking about here — for example, the letter ‘A’ beside a column on a page, which tells the reader to read that first, and the column marked ‘B’ second. Usually, though, these kind of metamarks are what we call the ‘paratext’ (a term which also includes features like headers, page numbers, rubrics, etc), and are included in the original creation of the document. And yet not relevant as ‘content’? Possibly this paratext-metamark is not the main preoccupation of those responsible for the TEI documentation. The main page gives a link to a section of the ‘Primary Sources’ page, which offers this clarification:

By metamark we mean marks such as numbers, arrows, crosses, or other symbols introduced by the writer into a document expressly for the purpose of indicating how the text is to be read. Such marks thus constitute a kind of markup of the document, rather than forming part of the text.

So metamarks are the original markup, and like markup, are meant to be ‘unseen’ by readers. Appreciated with respect to how they orders the content, but otherwise ignored.

Still, this description seems problematic. How are metamarks separate from any other kinds of marginalia? For all of us working on the Blake Marginalia project, why don’t we treat all of Blake’s writings in his books — like his habit of scrawling ‘Wrong!’ alongside the Lavater aphorisms — as metamarks? Any marginal signs, by coexisting with the content, alters the reader’s perception of the original work. And according to the documentation, the metamark is special for indicating a ‘deliberate alteration of the writing itself, such as “move this passage over there”’. Clearly, this is an element for which examples are more useful than description.

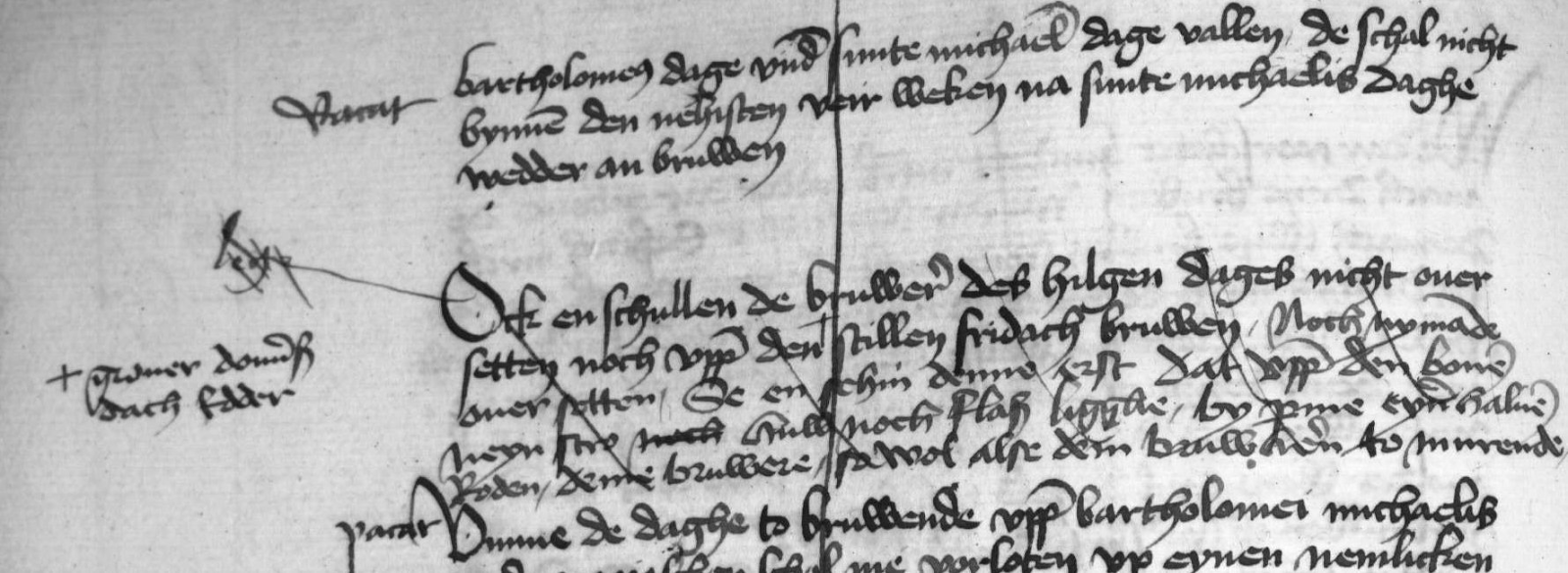

The first example given: scribal markings from a 15th century manuscript, in which the scribe mistakenly missed out a line when writing a paragraph. Writing it in the margin instead, the small + found here and interlineally in the text indicate that the new line is to be placed there. Logical. But clearly this element, with its ambiguous interpretation, has a broad range of use. Searching further through the reams of TEI documentation available online, I found instances of <metamark> being similarly used to describe the sequence of newspaper clippings in a notebook, editorial markings like ‘stet’, the cancellation of material, and the variant readings of manuscript lines. And judging by the argument threads in the forums, a lot of other users seem equally confused about whether they’re applying the element correctly.

The Blake Marginalia

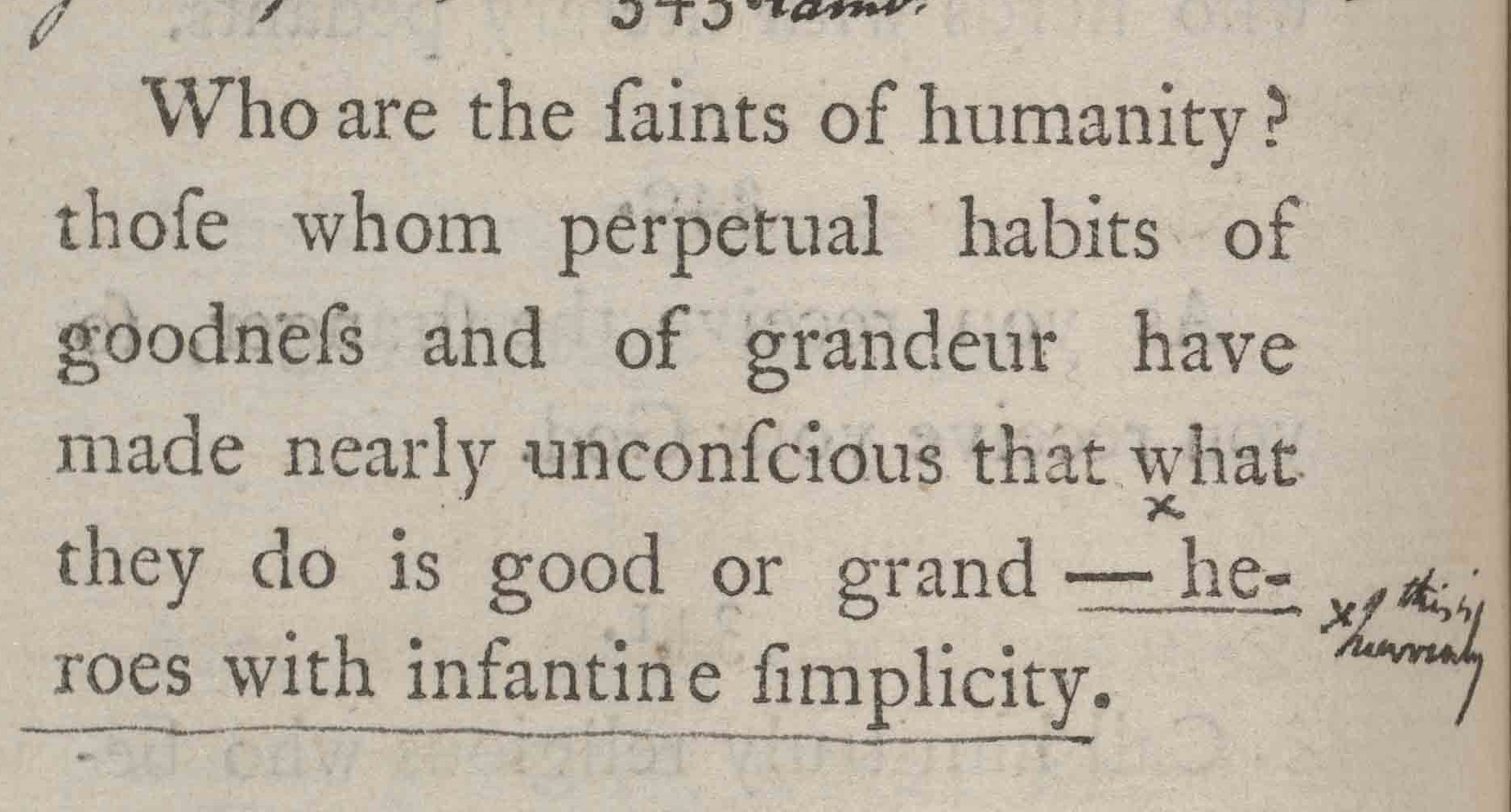

So we come to the Blake Marginalia project and its team, who so far have found at least 2 examples of what we think count as <metamark>, and which do and do not conform to the basic description. Here’s one:

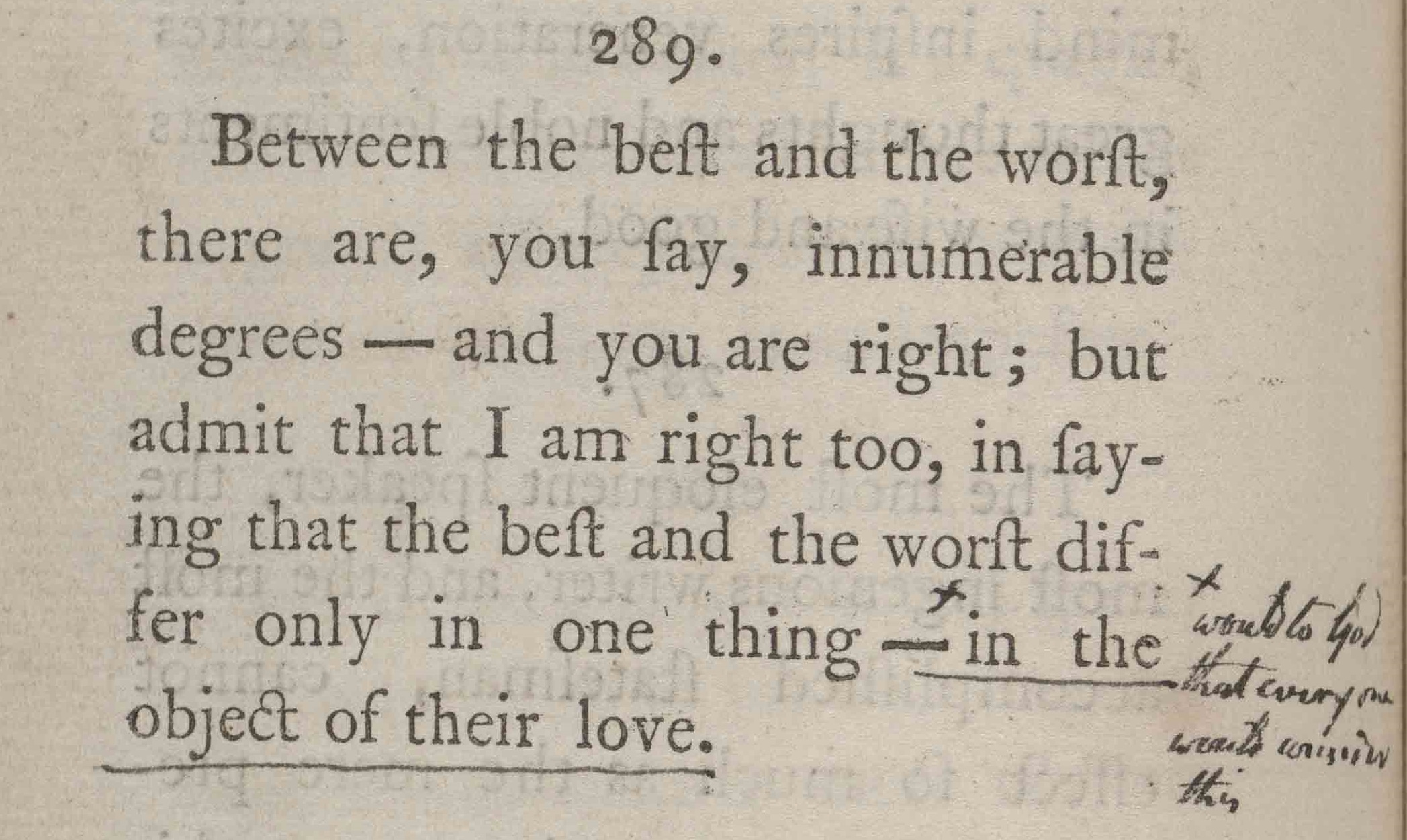

And the other:

Like in the first TEI example, the <metamark> is a small + found both in the typographical line and next to a marginal annotation. As with that first example, the reader is meant to associate this marginal note with that line — by inserting it into that space? For the first example, the reader would then be supposed to read:

Who are the saints of humanity? Those whom perpetual habits of goodness and of grandeur have made nearly unconscious that what they do is good or grand — this is heavenly heroes with infantine simplicity.

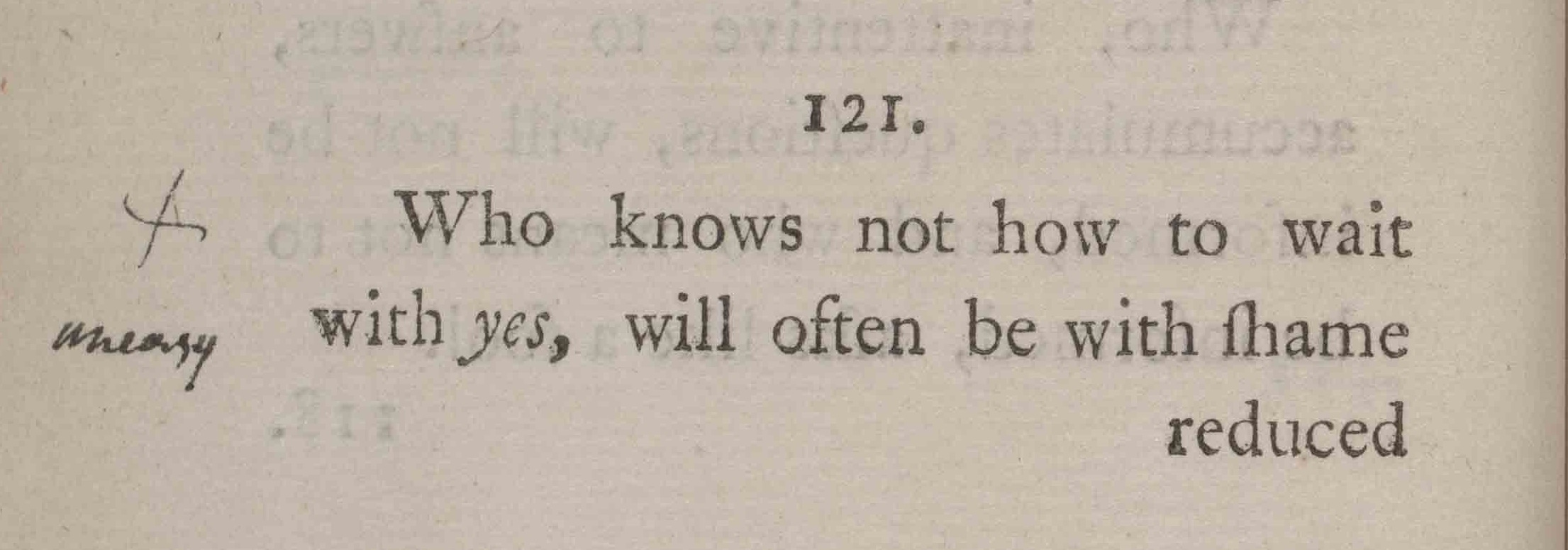

Maybe not entirely unreasonable, but it doesn’t quite seem to scan. The application of this function to the second example is even more absurd –- “would to God that everyone would consider this” is clearly a comment separate from the original aphorism, not meant to form part of it. So possibly the mark is merely meant to draw our attention to the marginal comment, and its relevance to that place in the text? If so, it’s hard to see this as constituting a ‘deliberate alteration of the writing itself’. The + might just be another piece of marginalia, another type of ‘highlight’, a symbol used to draw our attention to the relationship between the underlined section of the aphorism and the marginal note, which is already apparent through their physical proximity. As a signal to the reader, the + mark is unnecessary, superfluous. And yet Blake, very frequently in this book, draws similar crosses next to other marginal notes, which appear to us completely different to the one on page 118. For example:

So really, all that differentiates this symbol from the other two examples, is that there are two separate symbols there: one in the margin, one in the text. It’s only our awareness with paratextual features like editorial ‘insert here’ marks, that lead us to suppose that this is an important distinction. So, two questions for the Marginalia group — should they be specially marked at all? And if so, do we use <metamark>?