My contributions to Hell’s Printing Press typically investigate aspects of my own job at the WBA—illustration markup—and focus on the process of textual tagging (see my earlier post about textual tagging broadly as well as studies of the tags “streams of gore” and “lunging”). Assigning tags from our list of terms is both an illuminating and challenging process as Blake continually experimented with new iconography, forms, and materials. Tagging specific figures from literature, religion, and Blakean mythology often involves research to identify characters such as Lamech, Libicoco, and the “nameless shadowy female.” However, some of the most difficult tags to assign, I have found, are those associated with mental states and emotions.

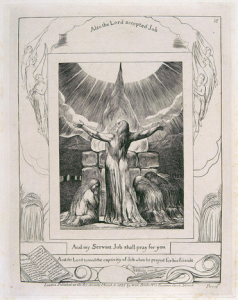

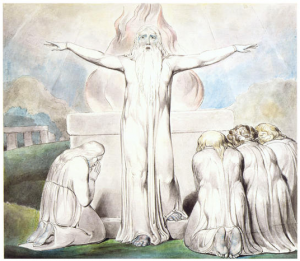

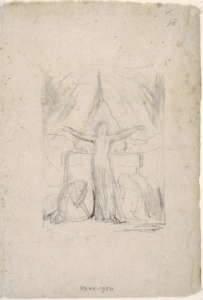

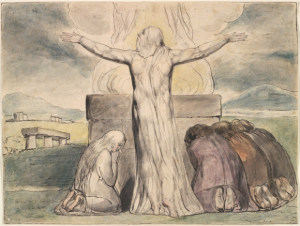

The WBA search term vocabulary includes many terms associated with emotions: proud, fear, anger, melancholy, terror, exhausted, envious, surprise, and grief, among others. Examining the similarities between the designs provides insight into how Blake crafted iconography associated with emotional states as well as how we, as WBA editors and project assistants, interpret facial expression, body position, and action in relation to certain emotions. For example, when searched, the term “ecstasy” appears as a text tag in five separate works. Four are related to Blake’s illustrations for The Book of Job either as finished works or preparatory designs. Ecstasy, here, becomes associated with religious ecstasy and a particular cruciform posture with arms extended horizontally. Moreover, in all four works, the fiery altar behind Job also contributes, at least implicitly, to this understanding of ecstasy as hot and passionate (more in line with the term’s erotic connotations) in addition to its religious associations as an almost trance-like state. The addition of the blazing sun above the altar in the engraved image only furthers this association of ecstasy with a fiery, divine, passionate heat or light.

Clockwise from top left: Illustrations to The Book of Job, object 20; Illustrations to The Book of Job, The Butts Set, object 18; Illustrations to The Book of Job, The Linnell Set, object 18; Sketchbook containing drawings for the Illustrations to The Book of Job, object 24.

Indeed, Blake admired the work and life of St. Teresa of Ávila, a Spanish mystic known for her ecstatic visions, and he references Teresa as a guardian of the gate of Beulah in Jerusalem. He may have been familiar with Bernini’s famous Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647-52), as engraved reproductions of the work, such as this example by Benoist Thiboust, were circulating in London in the late eighteenth century. Bernini’s sculpture similarly blends religious and erotic ecstasy in the saint’s body position and expression. Like Blake’s incorporation of fire and sun, Bernini also privileged light in his representation by illuminating the work with a hidden window for natural light, magnified by the gilded stucco rays in the background. Thus, Blake’s iconography of religious and erotic ecstasy would have been recognizable to many viewing the illustration to The Book of Job.

Left: Jerusalem the Great Emanation, copy F, object 72, c. 1827. Right: Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1647-52, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome.

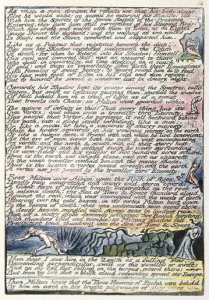

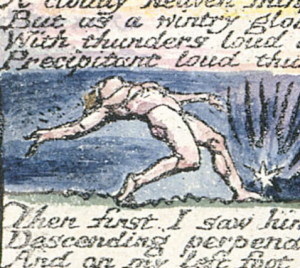

The final work in the WBA that includes “ecstasy” as a text tag, object 14 from Milton a Poem, copy A, also simultaneously suggests both religious and sexual ecstasy. As in the previous designs, the ecstatic figure extends his arms horizontally in a cruciform posture. He also arches backward and spreads his legs. The illustration description explicitly notes the ambiguity of the ecstasy: “This posture suggests crucifixion or a moment of ecstasy, religious and/or erotic.” The description suggests that the figure is William Blake himself in the moment that Milton, in the form of a comet, descends into his tarsus—a moment narrated in the plate’s text, lines 48-51.

Milton a Poem, Copy A, object 14, c. 1811 (detail at right)

By depicting himself in a moment of ecstasy, Blake further expands his understanding of the emotional state to include reading and writing, here in relation to Milton. His encounter with the famed English author is represented as not just intellectual but highly physical—and likely painful—as well as emotional, even erotic. An investigation of “ecstasy” as a search term, then, allows us to examine how Blake experimented with its iconography in relation to religion, sexuality, artistic precedent, and his own ecstatic experience of reading, writing, and creating art.