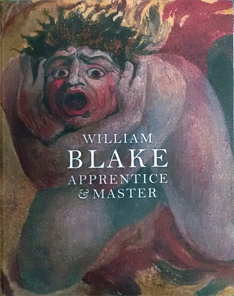

Every so often I publish a Q&A, and today’s guest is Michael Phillips, guest curator of the William Blake: Apprentice & Master exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, in 2014-15. I had a very murky idea of how an exhibition comes to life, so thought I’d find out.

SJ: I’m intrigued by the amount of work that happens behind the scenes to mount such an exhibition. How did it come about—did the museum contact you with a proposal and then the planning was joint? How long does it take to go from an idea to reality?

MP: Yes, in 2010 I was invited by the then director of the Ashmolean Museum, Christopher Brown, to discuss what might be possible. Following our discussion I was asked to submit a proposal for the museum to consider which, if accepted, I would be largely responsible for carrying out until the exhibition was ready to be hung. This was more than three years before the exhibition opened in December 2014.

I remember our meeting very clearly, my agreement to prepare a proposal for Christopher and his staff, and the brief. There were five main points: first, the exhibition at the Ashmolean was to be distinct from the comprehensive exhibition that I had been invited to help curate for Tate Britain in 2000 (amounting to over 400 works, one work being all 100 plates of the Mellon copy of Jerusalem), that subsequently was shown in a substantially edited-down form at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; and different again from the exhibition that I curated for the Petit Palais, that opened in Paris in 2009. The exhibition in Paris was intended to introduce Blake, especially as painter and artist-printmaker, as it was the first major exhibition of Blake in France.

Second, as the Ashmolean is the museum of the University of Oxford the exhibition should reflect its context. In other words, demands could be made of its prospective audience that would not have been appropriate either at the Tate or in Paris, where achieving maximum audience numbers was uppermost.

Third, wherever possible the exhibition should call upon materials in Oxford collections, most obviously, but not exclusively, from the archives and collections in the Bodleian Library and the Ashmolean. I could borrow from other collections in Britain (but not from North America as being too costly) to supplement those from Oxford, but the exhibition should demonstrate that London and Cambridge were not the only major resources in Britain for original research into Blake’s life and work.

Fourth, the exhibition was not to be a dry academic exercise. Its appeal should not only be in attracting a local audience; it should also be distinctive, and clearly important enough to attract visitors from London and beyond.

Finally, there was the matter of the catalogue. It should of course document the exhibition. But in its own right it should also make a substantial and lasting contribution to the subject.

With the advantage of having been at Oxford as a graduate student, and subsequently returning to further research its collections, I set about preparing a proposal. In the Bodleian was Richard Gough’s archive of the making of his Sepulchral Monuments of Great Britain, including the drawings in Westminster Abbey in preparation for engraving carried out by James Basire’s apprentice. The Ashmolean holds the greatest collection of the early and most inspired drawings of Samuel Palmer, made at the time he first met and visited Blake. The theme that would unite and upon which I could build the exhibition was clear, William Blake Apprentice & Master.