The Blake Archive has been preparing an electronic edition of selected letters by William Blake that will be published in installments over the course of the year. This edition, for which I have acted as a project assistant since 2010, has raised several challenges to the technical and editorial practices established in the archive’s earlier editions of Blake’s illuminated books, illustrations, and other visual designs. In a presentation called “Complicated Correspendonce” at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Documentary Editing (ADE) in Charlottesville, VA this August, I am looking forward to sharing these issues and the diplomatic responses being made to address them at the Blake Archive. I am also fortunate to have the chance to bring some of these questions with me to “Camp Edit,” the Summer Institute for Editing Historical Documents, which I will be attending in the lead-up to the ADE conference.

Of special interest, to me at least, are those pieces of correspondence that are not directly from Blake’s hand, but are too useful and critically valuable to exclude from an archive dedicated to his work. These documents, included in the standard print editions of Blake’s letters by G.E. Bentley, Geoffrey Keynes, and David V. Erdman, include contemporary letters to or about Blake by his friends, as well as a series of historically important letters from Blake to his sometime friend and patron William Hayley. The latter of these documents are now lost or destroyed, existing only through quotations and transcriptions published in an expanded 1880 edition of the first, posthumous biography of Blake, initially issued in 1863. The composition and publication history of this biography makes matters even less certain, as it was left unfinished at the death of its original author, Alexander Gilchrist. Gilchrist’s death left the completion of the first edition of the biography, and the expansions for the later second edition that include the letters by Blake in question, to a very loosely documented collaboration between multiple contributors and editors, including his widow Anne Gilchrist, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, and others.

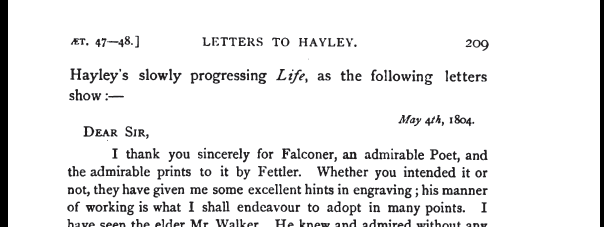

How, for example, should page 209 of The Life of William Blake (1880), including an unattested transcription of a letter by William Blake to William Hayley of May 4, 1804, be presented in a digital edition?

How might we distinguish the object by Blake and the surrounding material put there by the editors of his biography?

How might we best call attention to the uncertain status of the text in our visual presentation, editorial notes, and transcriptions?

How should we use the mixed digital media of the Blake Archive to do these things?

These sets of “complicated correspondence” will bring new agents, types of objects, and editorial precedents into the archive, and I hope to post some further updates about the progress of both the typographic and manuscript letters as these move toward publication over the coming weeks and months.

Your correction helpfully raises the question of the transcription’s uncertain accuracy and the origins of its content. Is this Blake’s slip, or a transcription error made by one of his later editors? Without the original manuscript, there’s probably no way to really know, which uncertainty will need to be addressed in the relevant notes for such situations as we prepare for publication. Thanks!

Not really relevant to your post, but I think the engraver of the Falconer plates mentioned in the snippet is actually Fittler rather than Fettler