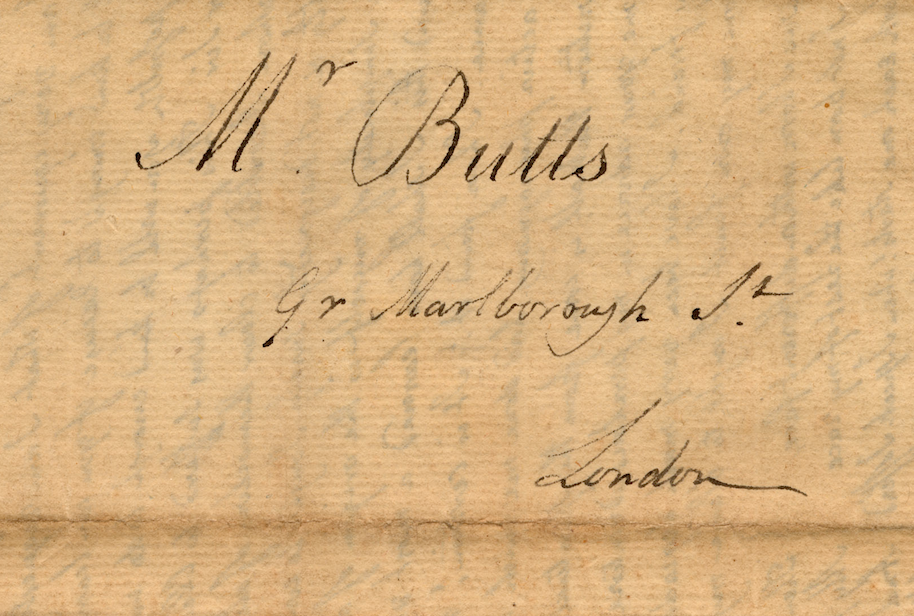

Transcribing and proofing literary work for digital publication can be a lot like translating. You get to know the content far better than you would from even an extremely slow and careful reading, because you’ve seen every sentence so many times. This was the experience I had several years ago when learning to translate Dostoevsky’s Хозяйка (The Landlady) for my language exam, and it was the experience I had this spring and summer while proofing a new batch of Blake letters for eventual publication. Throughout this process, William Blake’s August 16th 1803 letter to Thomas Butts became a particular favorite of mine (Find the complete text here: http://erdman.blakearchive.org/#b15).

This letter recounts what is often referred to as the “Scofield Incident,” named for the other party in the entanglement, John Scofield, a soldier who after an altercation with Blake in the latter’s garden in Felpham accused Blake of uttering a curse against the king. The accusation led to Blake’s trial for high treason in January of 1804.

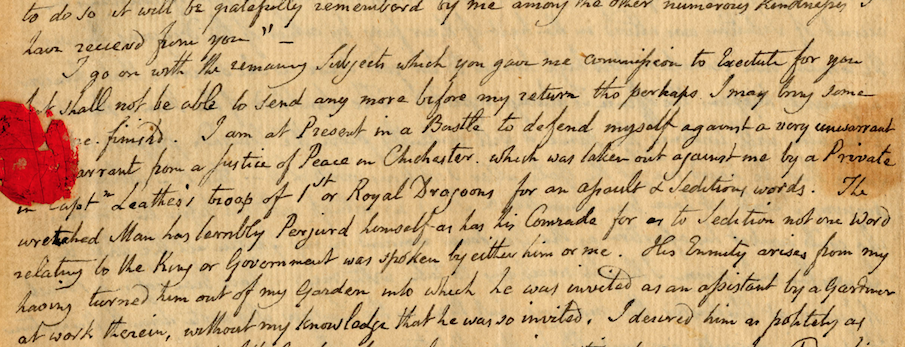

The August 16th, 1803 letter begins with a pretty standard series of personal and business-related communications. Blake talks about the 7 drawings accompanying the letter and his remaining commissions. He expresses concern for Butts’s declining eyesight. Then the letter takes an abrupt turn into more serious matters. Blake writes, “I am at Present in a Bustle to defend myself against a very unwarrantable warrant from a Justice of Peace in Chichester,” at which point he proceeds to recount his run-in with the irate soldier and the resulting fallout.

Blake’s description of the altercation itself is perhaps the most fascinating part of the letter. It truly reads like something out of Dickens; in other words, it is easier to visualize it if your imagination operates via cartoon characters rather than live action.

Blake first describes taking Scofield by the elbows and placing him outside the gate. He claims he intended then to retire but for the fact that Scofield continued to swear and threaten. Then it got wild:

“I, perhaps foolishly & perhaps not, stepped out at the Gate, &, putting aside his blows, took him again by the Elbows, &, keeping his back to me, pushed him forwards down the road about fifty yards–he all the while endeavouring to turn round & strike me, & raging & cursing, which drew out several neighbors;”

It’s hard not to detect some scrappy pride in Blake’s (possibly embellished) recollection of his own manhandling of Scofield. Even after all that happened as a result of the encounter, he isn’t willing to say he altogether regrets the course of action he took. Evidently, Blake was not a person to mess with.

And yet, one of the things I love so much about this letter is how it shows that as obstinate as he was, he was also capable of deep humility and even self-deprecation. He writes:

“I have been very degraded & injuriously treated; but if it all arise from my own fault, I ought to blame myself.”

Ten lines of verse then begin:

“O why was I born with a different face?

Why was I not born like the rest of my race?”

Of all the Blake letters to which I have been exposed, this is the one that most amply displays the various layers of his complex personality. Within just a few leaves, Blake’s pragmatism, his generosity, his cantankerousness and his conscientious, self-critical bent all come to the fore. It makes me particularly glad to know that eventually this letter will be electronically accessible through the Blake Archive. It’s just one of those Blake letters that everyone with an interest in Blake should read.

Good catch! I just fixed it. Thanks for pointing out.

Great work. Small typo in paragraph 3 – I think “soldier”

I’ve always visualised the altercation in the way you suggest – it’s not at all difficult to see how it developed, and how Blake lost his temper. But always chastening to come up against a sneaky and unprincipled opponent who thinks nothing of making accusations to a higher authority to get revenge. Very much enjoyed your short piece on this letter.