The previous occasion upon which we brought to your attention the documentation of Blake’s inimitable and exciting fiscal accounts was in mid-2016, so it’s about time we revisited the manifold problems plaguing the receipts project. The project has been gathering (only a little) dust while we paid attention to more pressing questions raised by the redesign, the Four Zoas display, the marginalia schema, not to mention the terrifying experience of recording tutorial videos! But, finally, the (all new) Receipts Team – comprising the brand new BAND member Emily Tronson, the not-so-new Alex Zawacki and myself – has reconvened and we’ve been trying to compile a list of objectives to guide our attempts to prepare a single, complete BAD with all the receipts in our possession. Here are some (hopefully) interesting thoughts and considerations we’ve come up with:

- As I mentioned, we’re trying to compile the lists into a single BAD. Since Blake’s receipts are scattered across different institutions, not all of them share the same provenance information. The receipts that we have come from the Westminster Library and the Huntingdon Library, which makes the problem reasonably manageable, but we’d like to compile them in a way that remains simple and effective even if we have to deal with a greater number of institutions. This is not to mention that we need to confirm the provenance information of each individual receipt, just in case there are any errors that have been handed down.

- The receipts were initially used by BAND as pedagogical resources to train new members to become comfortable with our VERY SPECIAL AND UNIQUE encoding practices, which often lead to a fair amount of hand-wringing for those who are more accustomed to TEI. Even though almost all the receipts have been transcribed, I still think that receipts should continue to be used to accustom newcomers to Blake-specific text encoding, and maybe Emily will check in soon with her experiences in this regard. In this context, I’ve considered making introductory tutorials for transcription based on the receipts, since they are concise yet challenging instances of Blake’s writing.

- Eventually, after we’ve compiled the current set of receipts into a single BAD, we’d probably like to acquire the rest of Blake’s receipts. It might be useful to compile and confirm the location of the objects we’re currently missing in order to expedite that process in the future.

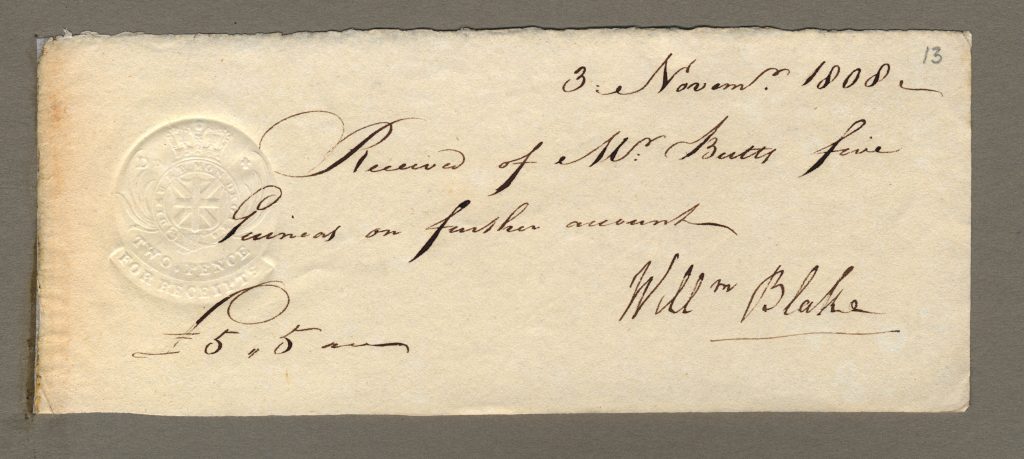

Working with the receipts is an incredibly rewarding experience. For newcomers to BAND, they often inaugurate the process of learning to interact with primary materials in a digital archive. From a historical perspective, they contain detailed information about Blake’s correspondents, his clients and the value of illustrated literary works in the contemporary cultural context. The revenue stamps in most of the receipts bear witness to what is possibly the implementation of taxation on newspapers, advertisements, pamphlets, and other forms of publication in the 18th century, according to the Stamp Act of 1712. Blake’s receipts may be read as staging a contest of value between governmental control and regulation and the freedom of artistic expression through the visual and verbal forms of stamp and signature. In this context, it is interesting to consider our role as digital humanists who both create and depend upon open-access archive of digital media, and how the ways in which we choose to transcribe and display the receipts comments on our own engagement with scholarship, copyright and collaboration within an increasingly monetized digital space.