During the past few months I have been one of several project assistants processing images for the online archive of Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly. Every now and then, hidden amongst the articles, minute particulars, and book reviews, I’ll stumble across a creative piece. Last week, while working on an issue from 1991, a poem caught my eye, but it wasn’t a poem by Blake; it was a poem about the Blakes, written by American poet Paulette Roeske. It’s called “Mrs. Blake Requests Her Portrait.”

William Blake, Catherine Blake c. 1805 (recto), graphite on paper, Tate Gallery N05188.

He keeps putting her off.

She, in her quiet way, insists.

Knowing he has a way with women,

romancing them in paint

the color of jewels, inventing

their most flattering features,

she expects he will exalt

her wifely figure,

the serviceable hips,

hair ripe with oil and smoke.

Over lunch he takes up

a dull lead stub and sketches

her profile: one miniature eye

downcast, half a mouth

and chin. Still chewing

the last bite of fish pie,

he adds a few squiggles for hair.

Pushing it across the table,

he trusts her to understand

that when he rendered Beatrice

crowned, Eve’s exquisite neck

and Bathsheba disrobed,

his vision was of Catherine.[1]

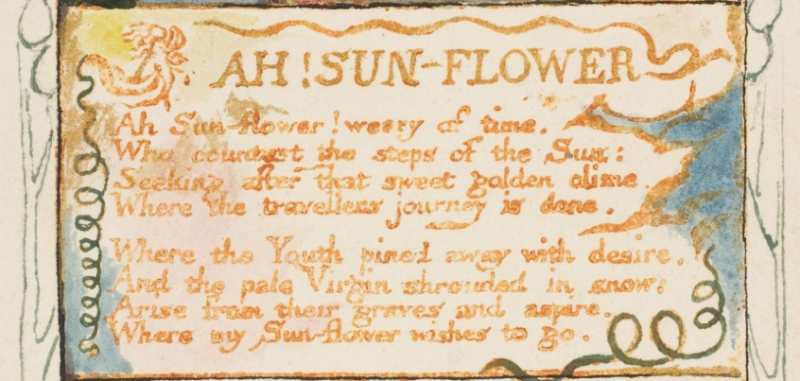

Roeske imagines an encounter between husband and wife, and her poem builds on contrasts between Blake’s formal, romanticized subjects and his intimate interactions with the woman he works alongside each day. The title presents a formal petition that seems more like a lady commissioning a painted likeness than a wife hinting to her husband for a sketch. The imagined response, though, is a casual denial. Blake “keeps putting her off” while she stubbornly “insists.” Roeske next imagines how Mrs. Blake perceives the other women her husband paints before contrasting that with the way Mrs. Blake might think of herself as a model. The notion that “he has a way with women” implies the slightest jealousy as she sees him “romancing them in paint / the color of jewels,” but Mrs. Blake still hopes he’ll “exalt / her wifely figure” as he has those of other subjects. Roeske’s physical description of Mrs. Blake seems limited, even stereotypical, but then we realize it comes from the presumed view of the subject herself. Mrs. Blake has dedicated her body to wifehood and work: the “serviceable hips” perhaps hint delicately at the children the Blakes never had, and the scents of oil and smoke in her hair reflect her daily labor, both in the kitchen and in the printing workshop. Mrs. Blake “expects” her husband to “invent” these ordinary features anew, to transform them into smooth curves and perfect curls, but he does not. Roeske’s mundane yet strangely tender encounter between the artist and his wife attempts to explain why. When he finally relents, Blake works right through lunch, holding “a dull lead stub” in one hand and a forkful of fish pie in the other as he dashes off a quick profile sketch. The watercolors have given way to graphite, and the full, idealized figures are replaced by “one miniature eye / downcast, half a mouth / and chin,” and “a few squiggles for hair.” Mrs. Blake’s commission has been fulfilled, but she has not received the portrait she expected.

In the last few lines, Roeske suggests that Blake’s quick sketch of Catherine’s profile hides a truth rooted in affection: he envisions her as he renders numerous historical figures. This conclusion brings to my mind Christina Rossetti’s “In an Artist’s Studio” (1856), where “[o]ne face” and “[o]ne selfsame figure” become “[a] queen in opal or in ruby dress, / A nameless girl in the freshest summer greens, / A saint, an angel,” or any other figure the artist chooses.[2] Most scholars assume that this one face and figure is Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s model and wife Elizabeth Siddal, whom he sketched and painted dozens of times, both in her own right and as a muse for various historical figures. While Roeske adopts a similar premise in her poem about the Blakes, her tone seems much more forgiving. Roeske’s Blake, like Christina Rossetti’s artist, paints “exquisite” women. When drawing from the “vision” of his wife, though, Blake the artist does not “fee[d] upon her face” like Rossetti accuses her brother of doing to Siddal;[3] instead, Roeske finds admiration rather than consumption. Blake “trusts her to understand” that, even though he does not paint her portrait, he has painted her many times.

I think Roeske’s poem raises some interesting questions, especially when she uses the word “vision” to describe how Blake sees his wife. Does Roeske make Blake’s partner a literal model, a face from which he draws as he paints these other women? Does “her wifely figure” indeed appear romanced as Beatrice, Eve, or Bathsheba to exalt the real woman with whom he lives and works? Or does Roeske suggest that, like the artist of Rossetti’s poem, Blake sees Catherine “[n]ot as she is, but as she fills his dream”?[4] Perhaps Mrs. Blake expects to be invented, but perhaps she suspects she already has been over and over by the visionary artist casually munching his fish pie across the ink-stained table.

[1] Paulette Roeske, “Mrs. Blake Requests Her Portrait,” Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly 24.4 (1991): 157. For each of the figures Roeske mentions, I have linked an image from The William Blake Archive.

[2] Christina Rossetti, “In an Artist’s Studio,” in Christina Rossetti: The Complete Poems, ed. R. W. Crump (New York: Penguin, 2001), lines 1-2, 5-7.

[3] C. Rossetti, line 9. The Rossetti Archive provides access to several such images. For example, D. G. Rossetti painted Siddal as the Virgin Mary in 1857. I’ve also linked a roughly contemporaneous sketch of Siddal above.

[4] C. Rossetti, line 14.