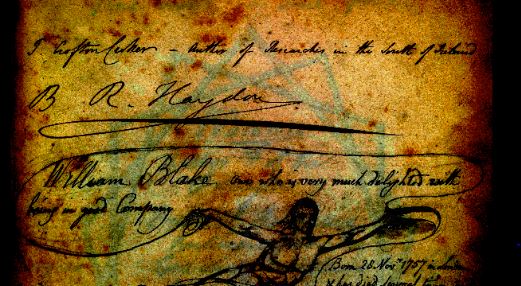

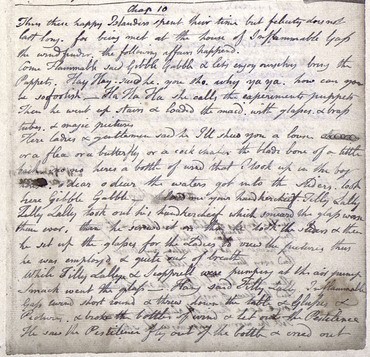

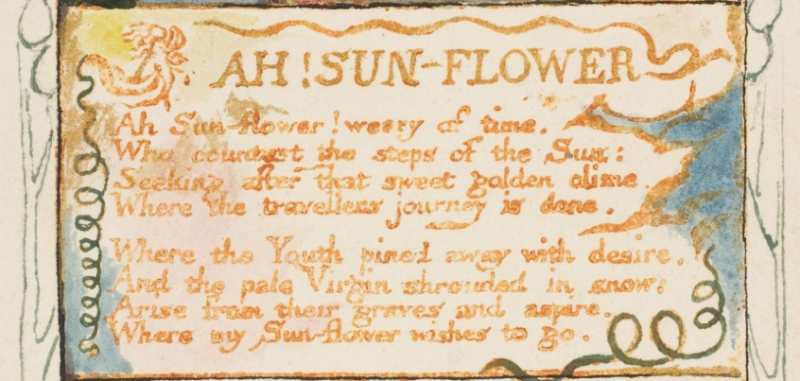

In the past month, I’ve transitioned from working on Blake’s letters and begun transcribing and building the BAD for “The Phoenix,” a newly discovered work by Blake whose provenance is (most conveniently) recorded in Bentley’s Blake Books supplement, one of BAND’s go-to reference works. Written in various shades of colored ink (and in a careful, vastly neater hand than Blake’s normal handwriting), “The Phoenix” is a brief, charming piece of verse dedicated to Mrs. Elizabeth Butts, wife of Thomas Butts, a clerk in the office of Britain’s Commissionary General of Musters and one of Blake’s main patrons from the years 1794-1806.

Aside from its simplicity and whimsical, lighthearted tone, what interests me most about this piece is how it reveals Blake’s dependence on—and consequently, the necessity of expressing generosity towards—the small circle of patrons who commissioned work from him. When we look at Blake’s letters to Butts (found in Erdman), Blake never fails to inquire after Mrs. Butts’s health and often invites the coupl e to stay in the small cottage he shared with his own wife, Catherine, in the pastoral town of Lambeth. He also occasionally writes verse to both Mr. and Mrs. Butts in the text of his letters, perhaps to flatter as well as honor their long friendship. Fortunately, Blake’s relationship with Butts remained amiable; in fact, it is because of Butts’s patronage that Blake’s finest works (including over two hundred Biblical watercolors and tempera paintings, at least four sets of watercolor illustrations to Milton’s poetry, the first series of illustrations to the Book of Job, a group of large color prints, and some copies of Blake’s major writings) were preserved and are now available to us today.

e to stay in the small cottage he shared with his own wife, Catherine, in the pastoral town of Lambeth. He also occasionally writes verse to both Mr. and Mrs. Butts in the text of his letters, perhaps to flatter as well as honor their long friendship. Fortunately, Blake’s relationship with Butts remained amiable; in fact, it is because of Butts’s patronage that Blake’s finest works (including over two hundred Biblical watercolors and tempera paintings, at least four sets of watercolor illustrations to Milton’s poetry, the first series of illustrations to the Book of Job, a group of large color prints, and some copies of Blake’s major writings) were preserved and are now available to us today.

“The Phoenix” reminds us that, across time, writers and artists (including the visionary Blake) are not exempt from material conditions, and so must “pay it forward” to their acquaintances. Finding friends and thanking them—whether in a letter, through the quality of a commissioned work itself, or by composing a poetic tribute to the patron or to members of the patron’s family—was, for Blake, not only a matter of personal and professional courtesy, but of survival. Patrons (particularly happy ones) impacted Blake’s livelihood, as well as his ability to carry on with his other work.

Luckily for us, Mrs. Butts recognized the value of “The Phoenix” and kept it until the end of her life. It was passed down through the family and later sold to the British Library, now flying to the Blake Archive “on glancing Wing.”

—